Let’s be real for a second. If we were ranking cars by 0-60 acceleration times, or movies by numbers of tickets sold, we could easily come up with an indisputable Top 20 list.

Blues turnarounds, however, are not so quantifiable. Winners exist solely in the ear of the beholder—that’s you. So while we can’t guarantee that the extensive collection of turnarounds that follows will prove to be your top 20 favorites, we have done everything possible to ensure the best chance that you will, at the very least, discover some inspiring new blues turnaround approaches.

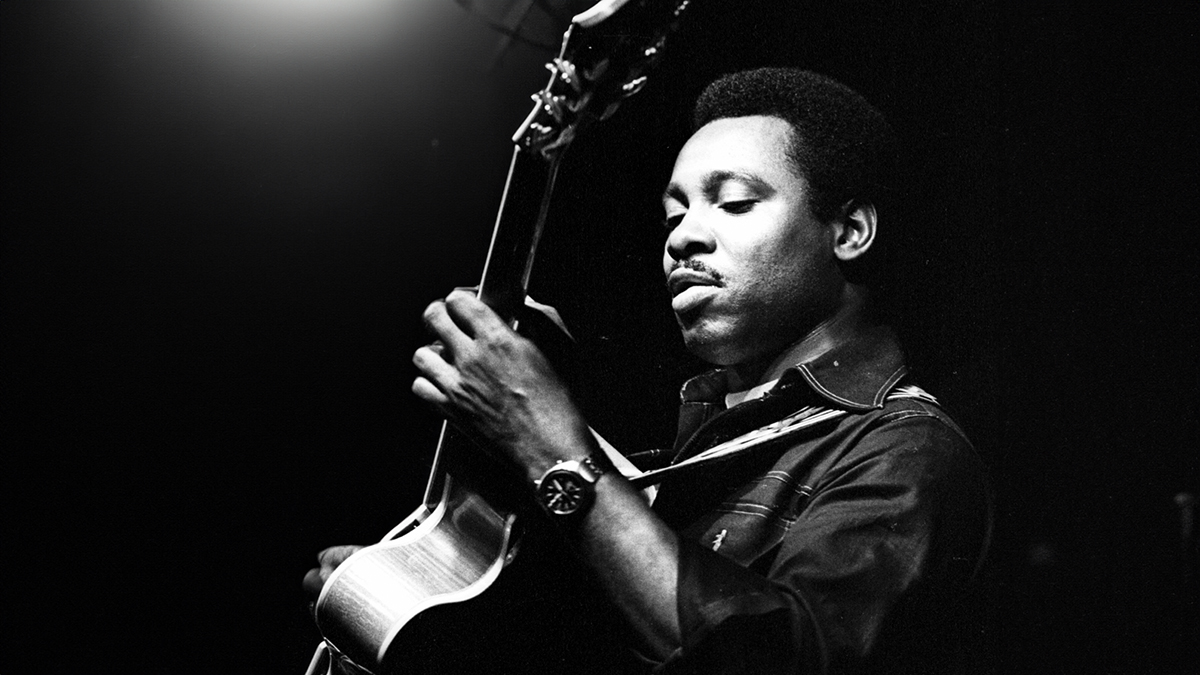

To that end, we have recruited renowned jazz guitarist Sid Jacobs to contribute insight and turnarounds of his own in these pages.

Remember: Few musical moments are as climactic as the final two measures (the “turnaround”) of a 12-bar blues. It’s during bar 11’s big, satisfying two-bar lead-up to the V chord at the end of bar 12 that you can make your strongest statement, so why not wrap up the cycle with a powerful closer? With that in mind—spanning everything from bonehead-simple single-note lines to complex contrapuntal cadenzas—here are 20 turnarounds every pro guitarist should know.

THE BLUES DESCENT

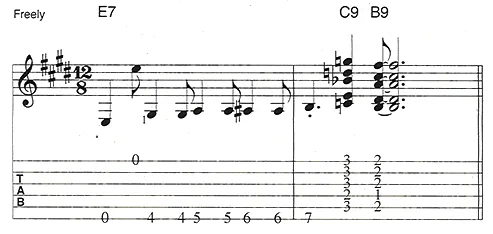

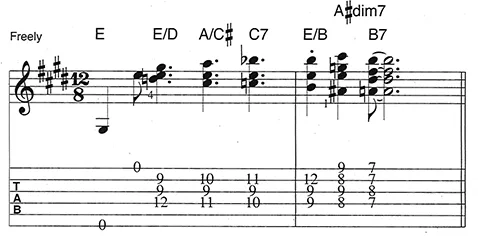

The most common type of blues turnaround riff is one that employs the simple descending line in FIGURE 1. Starting on beat two of this lick’s opening bar (which, of course, is measure 11 in the 12-bar cycle), this chromatic descent drops you from the 7 to the 5 (D to B, here in the key of E), leading you straight to the V chord (B7).

Tip: Most blues turnarounds (this one included) work equally well as intros, which is why you so often hear them used as two0bar pickups at the beginning of blues tunes. They also work as song endings, in which case the final chord is usually changed from the V to the I (for example, B7 becomes E7, in the key of E).

“This little descending line,” says Jacobs, playing FIGURE 1, “is so universal, it transcends the blues. Once you begin studying music seriously, you start recognizing it everywhere, in great songs from every genre.”

FIGURE 1

While FIGURE 1’s line is eternally useful, it is a bit bare-bones. It’s more a bass part than it is a blues guitar lick. With so many strings at your disposal, why not flesh things out with some high-E jangle, as in FIGURE 2? While playing this phrase, let the high E continue ringing each time you pick it (or pluck it, if you’re employing a fingerstyle or hybrid pick-and-fingers attack), and it will a generate compelling Billy Gibbons–style quarter-note cross-rhythm against the 12/8 bass part below.

FIGURE 2

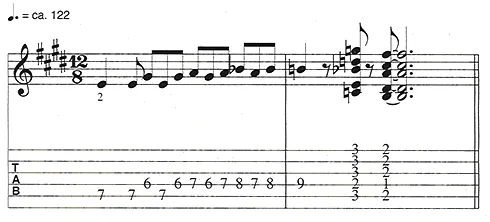

Another approach to dressing up FIGURE 1’s classic blues descent is simply to add parallel harmony, as in FIGURE 3, where our fifth string walk-down is harmonized with a parallel melody on the third string, while ringing open strings cheer us on.

FIGURE 3

Also, know that your b7-to-5 descent doesn’t have to be on a low string, as in FIGURE 4, which transplants the b7-to-5 line up to the second string.

FIGURE 4

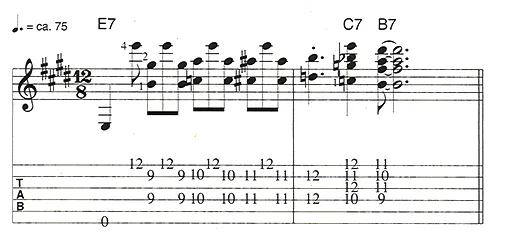

There are countless ways to play this blues descent. “When I was a kid, I used to play it all the time in the form of this lick in the key of G,” says Jacobs, playing FIGURE 5. “Here, you see the line on the fourth string.”

FIGURE 5

The interesting thing is that sometimes, even if you start your descent on a chord tone other than the b7, you can still imply the 7-5 drop, as we do in FIGURE 6. Here, we have parallel four-note descents-one on the second string (starting on the 3, B) and one on the fourth string (starting on the 5, G)—while the open third string adds chime throughout. Tip: This lick sounds extra saucy if your bass player does descend from the b7 (F).

FIGURE 6

THE BLUES ASCENT

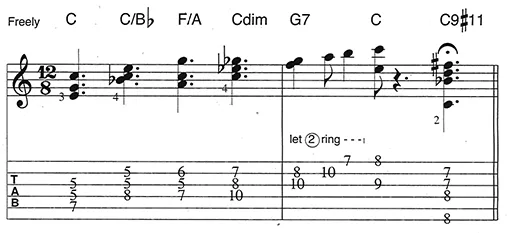

The other line you hear all time in blues turnarounds,” says Jacobs, “is the one that rises chromatically from the 3 to the 5.” In the key of E, this line (which again starts on the lick’s second beat) carries you from G# up to B, as in FIGURE 7.

FIGURE 7

Transplant this classic blues ascent up an octave and add a little melodic sequence pattern, and you have FIGURE 8, which evokes the famous turnaround in “Tell Me,” by Howlin’ Wolf.

FIGURE 8

Bump it up yet another octave so it occurs on the second string, add parallel harmony on the fourth string, and things start to sound fuller, as in FIGURE 9.

FIGURE 9

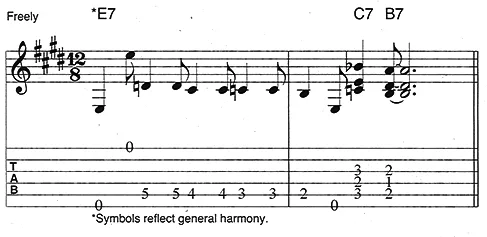

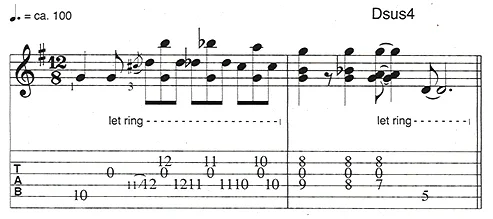

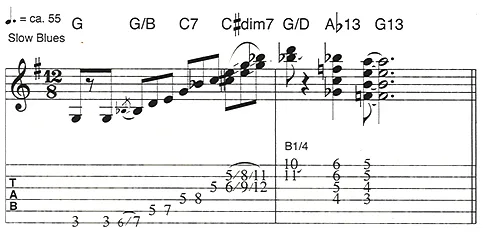

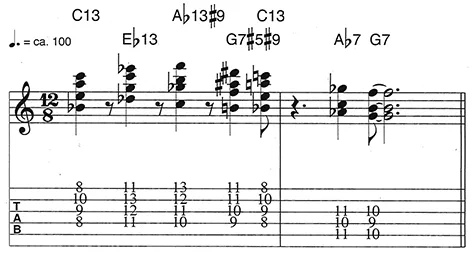

For a more sophisticated approach to the blues ascent, move to the key of G and take a spin through FIGURE 10, a tasty, slow 12/8 closer in the style of Larry Carlton’s final lick on “B.P. Blues,” off his 1986 live album, Last Night. Can you spot the blues ascent in this example? It’s in the chord symbols. You’ll hear it if, starting on beat two of bar 1, you play the lowest note in each symbol (B-C-C#-D), as a bass player reading the chart would. Start this example whisper-quiet, gradually building to a crescendo by the final bII-I (Ab13-G13).

FIGURE 10

CONTRAPUNTAL BLUES MOVES

In any genre of music, it’s pleasing to hear a pair of melodies that complement each other while traveling in opposite directions. So if we play our classic ascending and descending blues lines simultaneously, the result is a great-sounding specimen of strict contrary motion, as FIGURE 11’s popular turnaround proves. Here, back in the key of E, we ascend from the 3 (C#) on the second string while descending from the b7 (D) on the fourth string.

FIGURE 11

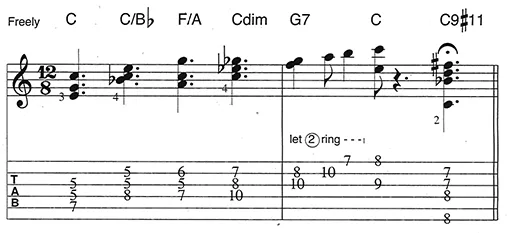

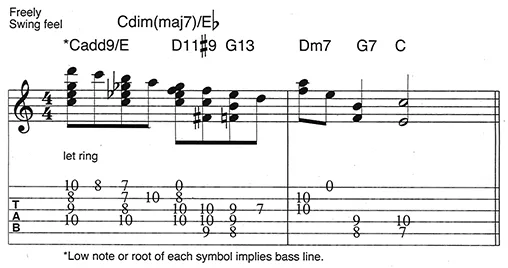

Switching to the key of C, Jacobs builds on this move in FIGURE 12’s closer, tagging Cdim before wrapping things up with a classic diatonic rise to the root in the first half of the second measure.

FIGURE 12

Next, in the piano-style turnaround shown in FIGURE 13, Jacobs expands to two distinct voices, again wrapping things up in bar two with the previous example’s diatonic rise in the upper melody.

FIGURE 13

HARMONIZED PENTATONICS

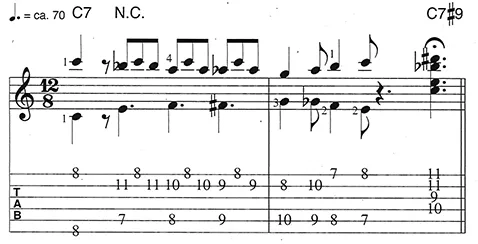

The first time you hear Jacobs play the series of descending grips in FIGURE 14’s meaty blues closer, the rich harmonies that fill your ears may initially obscure the fact that the approach he is employing is relatively simple.

FIGURE 14

“I’m just harmonizing a pentatonic blues line in C,” says Jacobs, who likes to throw in phrases like this on pentatonic blues heads such as Sonny Rollins’ “Sonnymoon for Two.” “If you play only the highest note in each chord, it becomes obvious that I’m just traveling down the C minor pentatonic scale. Here’s another one you can try [FIGURE 15].”

FIGURE 15

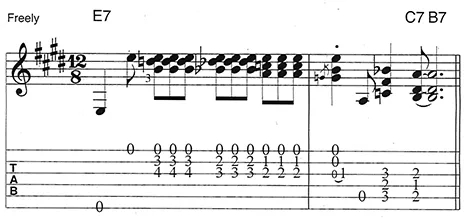

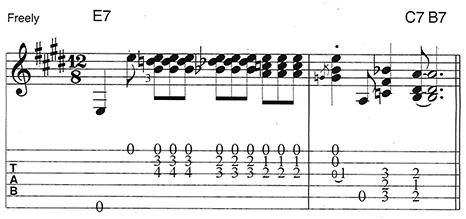

STEPPING OUT

With FIGURE 16, Jacobs reminds us we can also harmonize other scales besides blues scales to create compelling turnarounds and endings. Here, the blues notes are tucked into the chords beneath a diatonic descending line. “I’m simply harmonizing a descending C major scale, starting on the 2, D, in the highest voice,” says Jacobs, “and I’m climbing down an entire octave, D to D, before wrapping things up with a quick II-V-I [Dm7-G7-C].”

FIGURE 16

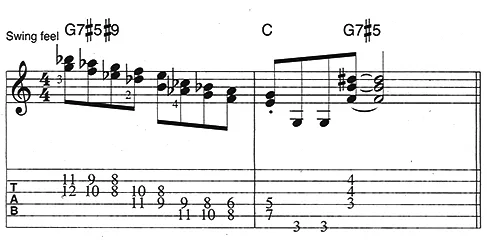

When you’re ready to apply a similar approach to the altered dominant scale—which naturally sounds great over dominant chords featuring one or more altered tones (such as the #5, b9, or #11), try FIGURE 17, which makes for a compelling intro in C. Here, Jacobs simply steps down the G altered-dominant scale (spelled G A B C# D# F) in parallel thirds, though you may notice some scale degrees have been notated as their enharmonic equivalents (for instance, A# becomes B ) to make the reading easier.

FIGURE 17

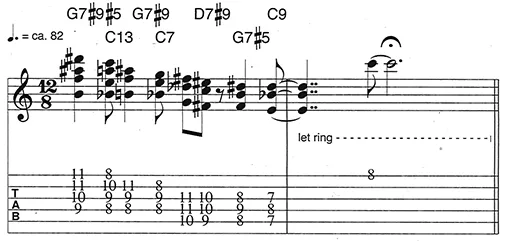

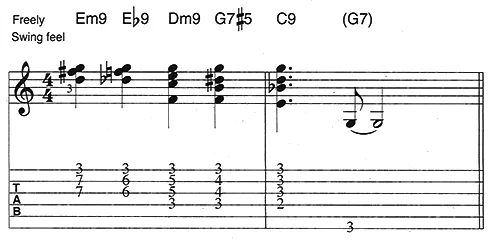

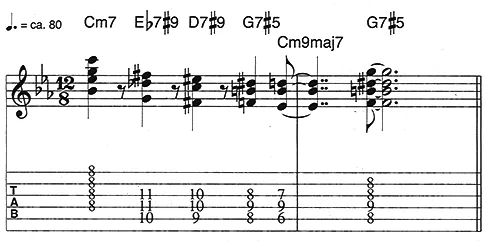

Asked to share a III-VI-II-V intro that would be useful for launching a “jazz” blues in C, Jacobs plays the Em9-E 9-Dm9- G7#5-based turnaround in FIGURE 18. (Notice that the VI chord in the progression, which would usually be an Am variety in our key of C, has been replaced with a convenient passing chord—its tritone substitute, Eb9.)

FIGURE 18

MINOR MATTERS

For our last two examples, let’s make sure we spread some turnaround love to our other 12-bar friend, the minor blues.

“Here’s a simple but useful C minor turn around,” says Jacobs, playing FIGURE 19, which he sometimes likes to cap with the pensive-sounding Cm9maj7, as written.

FIGURE 19

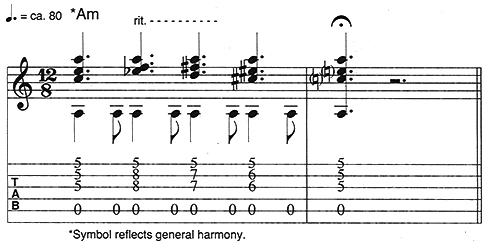

Finally, FIGURE 20—which is inspired by George Gershwin’s moody four-part vocal turnarounds on “Gone, Gone, Gone” (from the score he composed for the musical, Porgy and Bess), makes a dramatic closer in A minor, especially if you play it softly and apply a gradual ritardando.

FIGURE 20

Examples 19 and 20 are written as shuffles, while the previous pair was presented as 4/4 swing jazz, but you can easily change any phrase to either rhythmic feel. In fact, you’ll find it’s generally simple to rework the rhythms of any of this lesson’s examples to suit blues grooves spanning slow 12/8 to mid-tempo hard bop to fast funk, provided you’ve memorized the fretboard moves.

So, with that in mind, now is a good time to go through all 20 turnarounds once again to really burn them into your fingers. Otherwise, they, too, may soon be “gone, gone, gone.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Whether he’s interviewing great guitarists for Guitar Player magazine or on his respected podcast, No Guitar Is Safe – “The guitar show where guitar heroes plug in” – Jude Gold has been a passionate guitar journalist since 2001, when he became a full-time Guitar Player staff editor. In 2012, Jude became lead guitarist for iconic rock band Jefferson Starship, yet still has, in his role as Los Angeles Editor, continued to contribute regularly to all things Guitar Player. Watch Jude play guitar here.

“Write for five minutes a day. I mean, who can’t manage that?” Mike Stern's top five guitar tips include one simple fix to help you develop your personal guitar style

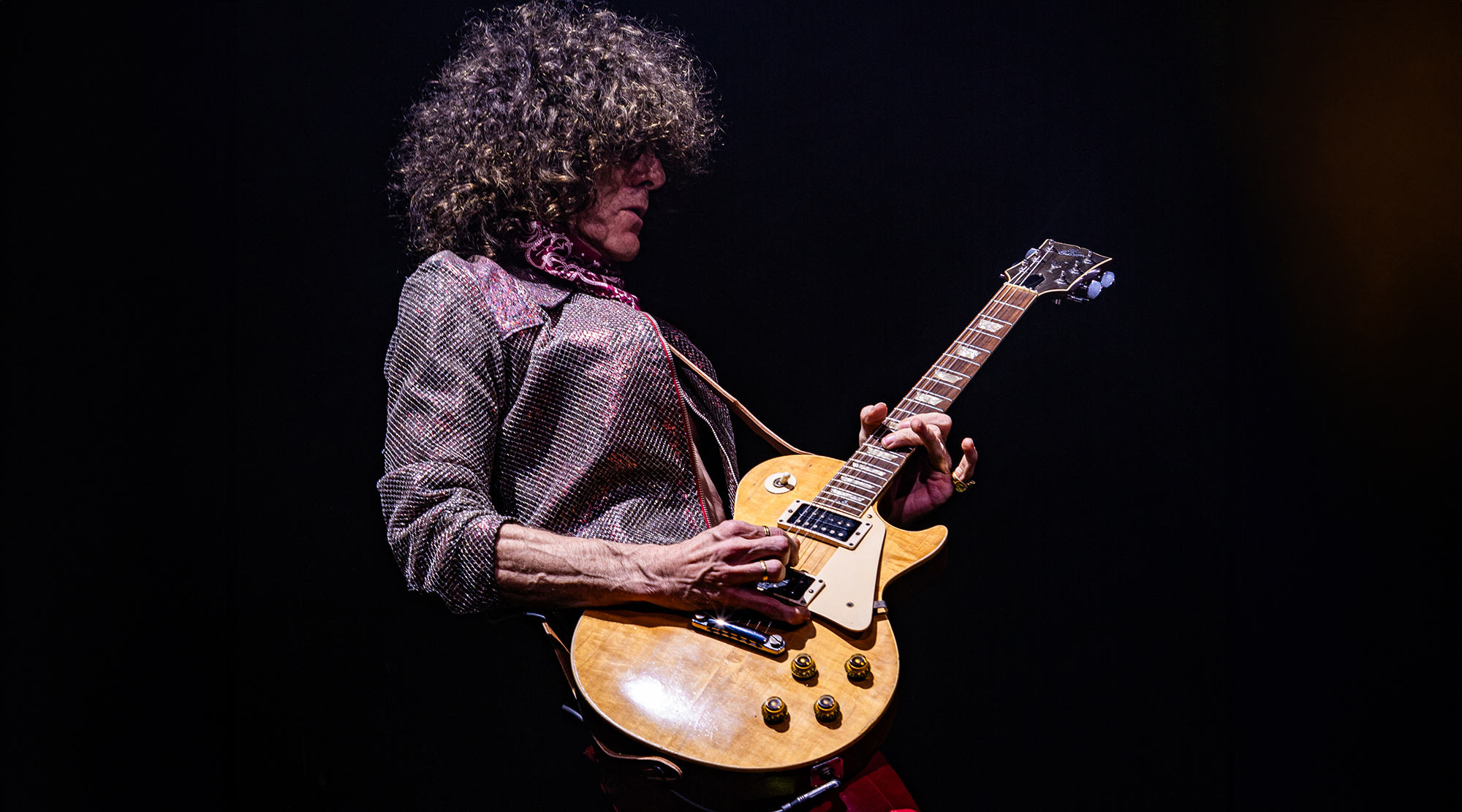

"It’s like you’re making a statement. And you never know where it’ll lead." Pete Thorn shares the tip that convinced Joe Satriani he was the right guitarist for the SatchVai Band