“I had him mix some paint there on the spot, and finally we came up with Fiesta Red!” With one decision, Fender increased the desirability — and future value — of a select few guitars

Fender custom colors were offered for a small upcharge after a handful of customers requested their guitars in special finishes

Beauty may be skin deep, but the custom-color finish on a Fender electric guitar from the late 1950s and ’60s adds a level desirability that runs through the entire instrument. Not only does the look of a custom color appeal to many players and collectors but the presence of this alternative finish — when original — adds considerable value to any vintage Fender that carries it.

Remarkably, the custom color concept developed rather casually at Fender. It was little more than a brief, almost throwaway mention at the bottom of Fender’s 1956 sales sheet for the Stratocaster, which was then still relatively new: “Stratocaster guitars are available in Du-Pont Duco colors of the player’s choice at an additional 5% cost.” Prior to that, some artists had directly requested special colors, resulting in Bill Carson’s Cimarron Red and Eldon Shamblin’s Gold Stratocasters, both made in 1954 soon after the model’s introduction, but there was no official system prior to that time.

Leo Fender’s longtime associate George Fullerton told author and guitar historian A.R. Duchossoir (as recounted in his book The Fender Stratocaster) that he initiated the idea of formally offering custom colors, and many accounts have similarly credited him.

“One day, I went down to a local paint store and I started to explain to the man what I had in mind,” Fullerton explained. “I had him mix some paint there on the spot, and finally we came up with a red color… Fiesta Red! I would say probably late 1957/early 1958. The custom colors came out about the time the Jazzmaster just came out. The reason I know that is because I had the color red put over one of the early manufactured Jazzmasters.” It’s worth pointing out that Fullerton didn’t invent Fiesta Red; the color appeared by that name on official Ford color charts at least as early as 1956.

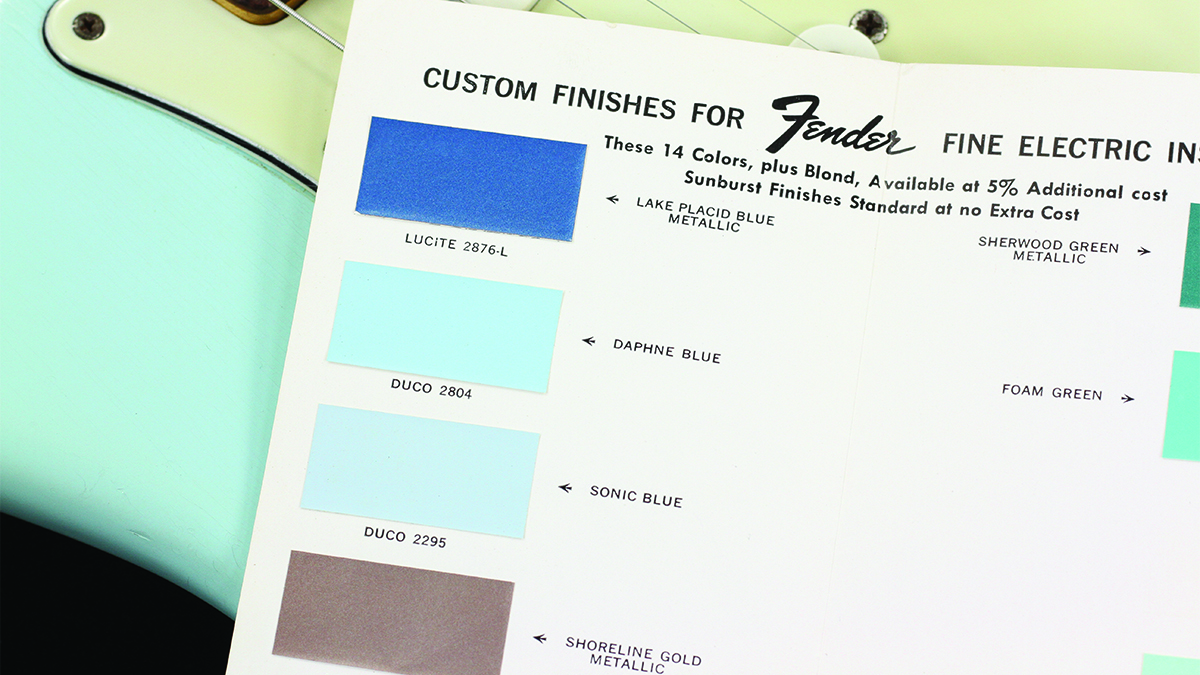

The custom-color phenomenon picked up speed in the late ’50s and into the ’60s, when a range of finish options were presented in an official list and supported with a Fender color chart. Published in 1960, Fender’s first formal custom-color chart included 14 official paint options: Lake Placid Blue Metallic, Daphne Blue, Sonic Blue, Shoreline Gold Metallic, Olympic White, Burgundy Mist Metallic, Black, Sherwood Green Metallic, Foam Green, Surf Green, Inca Silver Metallic, Fiesta Red, Dakota Red and Shell Pink. Each could be ordered through a Fender dealer at a five percent premium on the guitar’s list price. (An additional option, not listed on the chart but mentioned in its caption, was the blond finish that was otherwise standard on the Telecaster, and which was almost invariably applied over an ash body.)

In 1963, Shell Pink was dropped from the list and Candy Apple Red Metallic was added. Two years later, in 1965, Daphne Blue, Shoreline Gold Metallic, Burgundy Mist Metallic, Sherwood Green Metallic, Surf Green and Inca Silver Metallic were axed as well, replaced by Blue Ice Metallic, Firemist Gold Metallic, Charcoal Frost Metallic, Ocean Turquoise Metallic, Teal Green Metallic and Firemist Silver Metallic.

In what seemed quite a natural rock and roll tie-in, most of these colors equated to paints used by one or another Detroit automaker from the late ’50s to the mid ’60s. Fender’s custom-colored guitars could see their twins in cars made by Pontiac, Chevrolet, Ford, Cadillac, Lincoln, Buick, Mercury, Oldsmobile and DeSoto. And because guitars weren’t always built from the ground up with the custom-color option in mind, many were finished in standard sunburst before being shot with a custom-color coat and sent on their way. Over time, wear and tear would reveal the original finish.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When the Fender Mustang was introduced in 1964, the company folded the custom-color phenomenon into the new student guitar’s standard options, in a manner of speaking, by offering them in Red, White and Blue finishes that in later years have often been mistaken for Dakota Red, Olympic White and Daphne Blue. And while the introduction of the Competition Mustang series in 1969 seemed to bring with it guitars aligned to many metallic finishes on the custom-color chart, these were still given names like Competition Blue, Competition Red and Competition Orange, for example, along with the white racing stripes that helped to define them.

With pre-CBS Fender guitars in original standard finishes commanding ever-escalating prices, it seems obvious that the five-percent charge for custom colors was money well spent. A custom color on a pre-CBS Stratocaster will today add far more than five percent to its value, often something in the 25- to 30-percent range or even as much as a 50-percent premium for the particularly rare colors, as compared to standard-finish guitars from the same year and in similar condition. Not a bad investment then — or now.

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models

“A good example of how, as artists, you have to blindly move forward with crazy ideas”: The story of Joe Satriani’s showstopping Crystal Planet Ibanez JS prototype – which has just sold for $10,000