“He kicked me in the butt one night. I was playing rhythm and he said, ‘Go on. Play lead!’" Stephen Stills on the guitar skills he learned following Jimi Hendrix for two years. "He was my guru"

Stills said he also befriended Duane Allman while the future Allman Brothers Band legend was performing in the group Hour Glass in the late 1960s

Stephen Stills is considered one of the great leaders of the 1960s West Coast folk-rock renaissance. From his work with Buffalo Springfield to his long tenure with Crosby, Stills & Nash — and sometimes Young — he’s largely celebrated today for his vocal prowess in harmony with the latter group and his songwriting. Stills tunes like “For What It’s Worth,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” “Helplessly Hoping” and “Carry On” remain popular several decades on, making them a testament to his talents and enduring relevance.

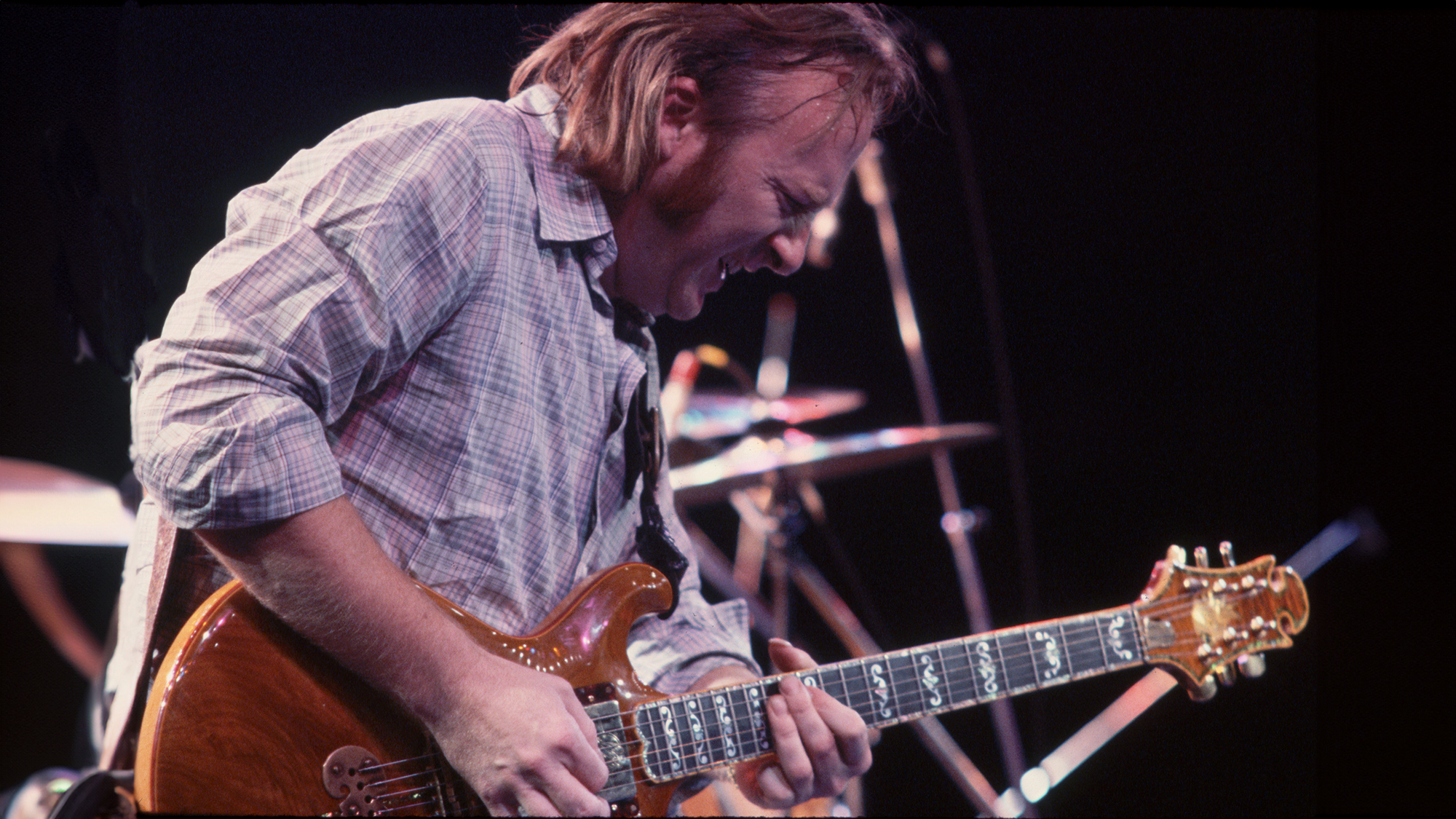

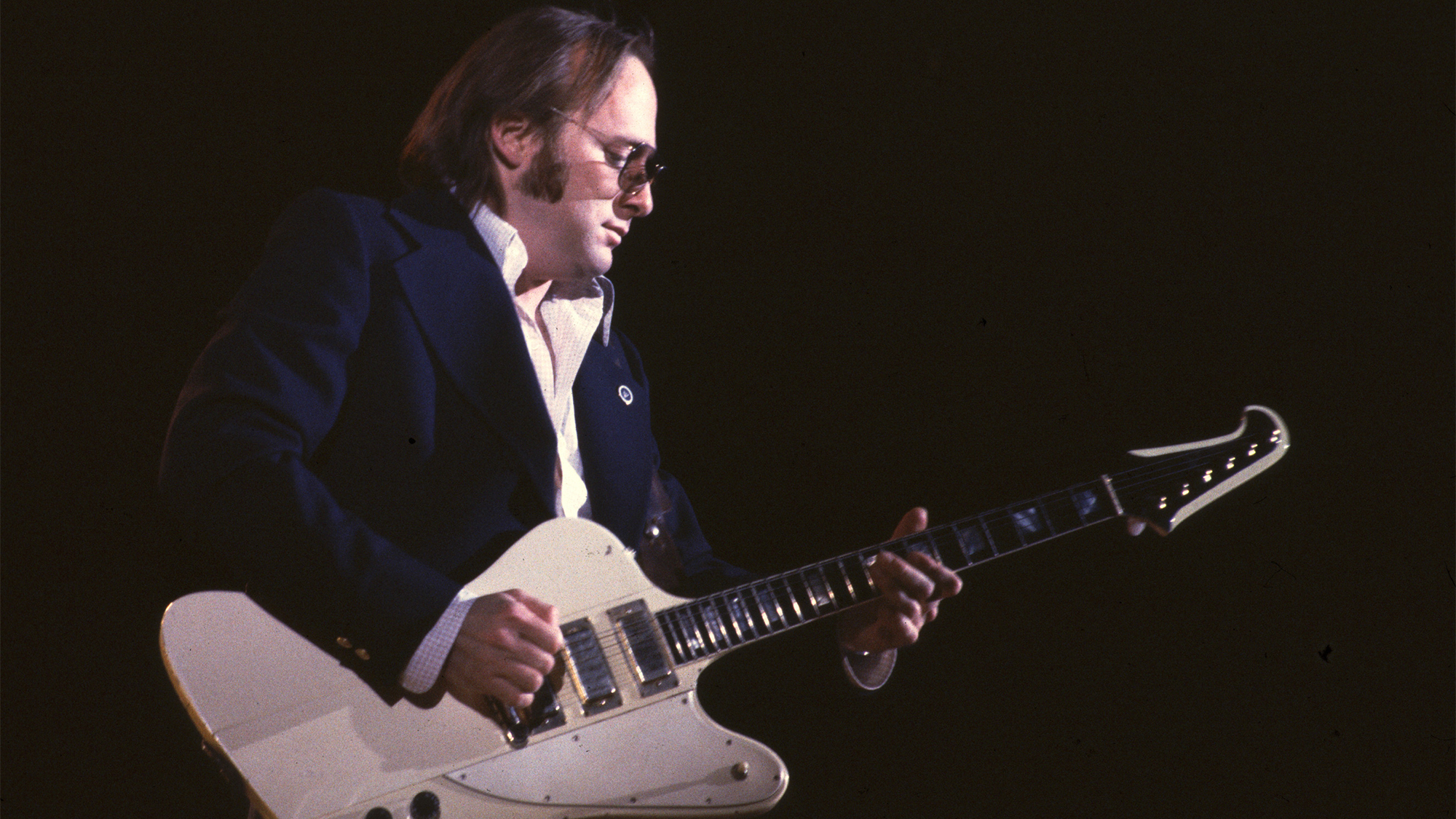

But Stills’ considerable guitar talents tend to be overlooked. Whether on acoustic guitar — such as the prewar Martins he’s favorted — or electric —including Gretsch White Falcons, Fender Stratocasters and Gibson Les Paul Custom — Stills proved himself a technically virtuoso and fiery performer. He got his first guitar, a Kay hollowbody electric, in 1962 at the age of 17 and began teaching himself, his interests shaped by blues and country as well as Latin music.

Stills was so talented as a player and songwriting that Randy Bachman recently admitted to stealing from him — a fact that was not lost on Stills.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that Stills began to take an interest in lead guitar playing. Like so many of his peers, he was influenced by Jimi Hendrix. But unlike everyone else, Stills got his lessons directly from Jimi — not just one but countless.

“I followed the dude around for two years learning how to play lead guitar,” he recalled to Guitar Player in 1976. “I literally followed him like he was my guru. People thought I was a groupie, but I wasn’t; I was going to music school.”

His friendship with Hendrix led Stills to jam with the likes of Buddy Miles — who drummed with Hendrix in Band of Gypsys — and Johnny Winter. But much of his time with Hendrix was spent one on one.

“Jimi and I played for 14 hours once at my house in Malibu,” he said. “We must have made up 15 rock and roll songs, but forgot them all because it wasn’t taped. We just played for the ocean.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Stills said it was Hendrix who pushed him to play lead.

“He kicked me in the butt one night,” he recalled. “I was playing rhythm with my eyes closed, and he said, ‘Go on. Play lead!’”

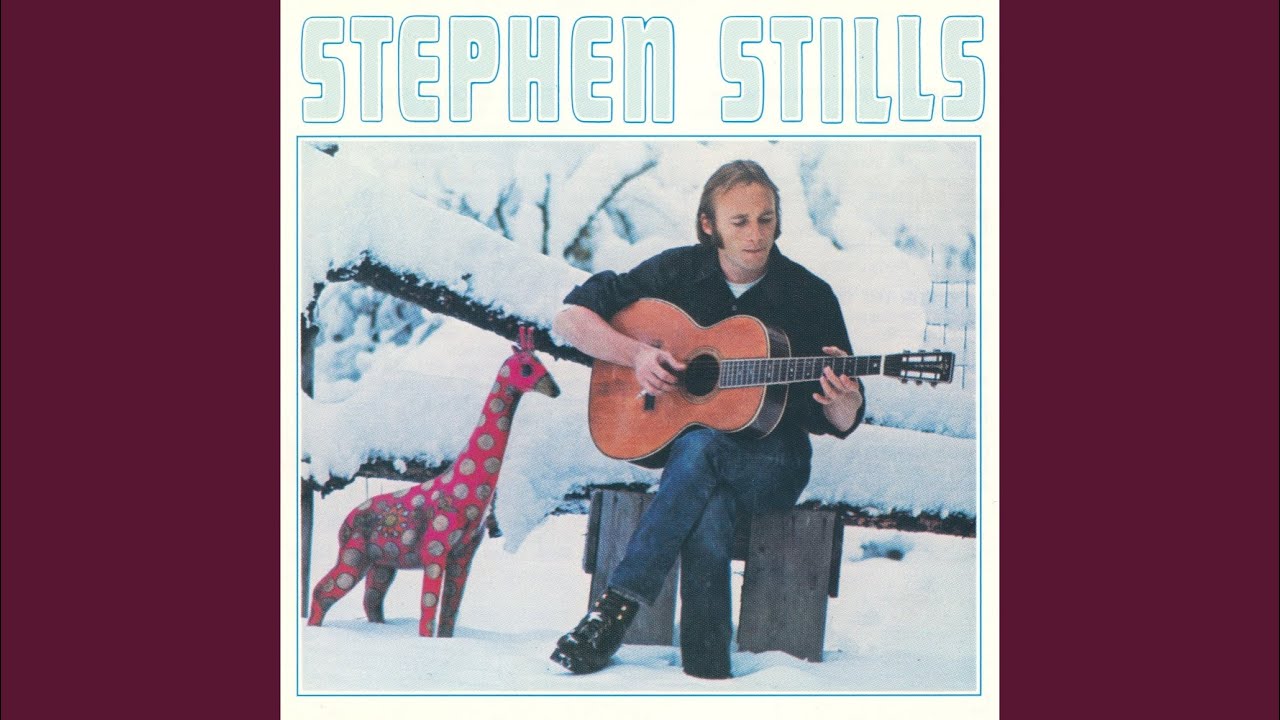

Fortunately, the two guitarists would spend some time in the studio together. Hendrix played lead guitar on "Old Times, Good Times,” from Stills' self-titled 1970 album. They also recorded Stills’ song “$20 Fine” on September 30, 1969, which was released on the 2018 posthumous Hendrix release Both Sides of the Sky, and a cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” with Hendrix on bass and vocals.

“Jimi and I got together as much as we could,” Stills said. “I always thought a good blues [rhythm] section that would take time to learn Jimi’s vamps and stuff would have really just set him free. God knows what he was hearing. I really didn’t hit my stride, though, until after he died. If he was still around, we’d be inseparable by now.”

Stills also clocked time with Duane Allman when Duane and his brother Gregg were performing in Hour Glass, the group they formed in Los Angeles in 1967. Hour Glass opened for acts like the Doors and Buffalo Springfield, which is how Stills came to befriend Duane.

“Every time we’d hit the same place at the same time, it was, ‘C’mon let’s play. Get the band. Who wants to play drums? Who wants to play bass? Let’s play, play, play.’”

Those jams with Allman added new aspects to what he’d picked up from Hendrix.

“The great thing about jams is learning — learning how to copy the other guy’s riffs,” Stills said. “A guy lays down a rhythm riff, you play against that. Then when it’s his turn, play the same rhythm he was playing with the same accents and so on.

“I’ll tell you, sometimes when I’m onstage now I see ghosts as I play my guitar. Sometimes they’re laughing at me. Sometimes they’re saying ‘right on.’”

Stills shared some of his hard-earned secrets about soloing and rhythm.

“The secret of rhythm — like my folk experience — is learning to Travis pick: getting rhythm in the thumb, getting with the bass, and getting that push beat to it. If you’re using a flatpick, you can go the same way. You learn how to palm. You learn which position is the best to get the most out of a chord, because rhythm is basically dividing the chord into two parts. You’ve got the bass and treble, and you divide the measure up and play brmmm, chick, brmmm, chick. You’ve got to divide them up and use the damper in between.”

“There are relatively few great rhythm players in rock. Peter Townshend is one, Eric Clapton, Joe Walsh is one of the greatest, and Jimi Hendrix was actually a great rhythm player.”

On the subject of soloing, he noted the importance of practicing scales, saying it gave him the confidence he needed to take flight. Thanks to the skills he developed, he said, “You run up the neck, and you don’t miss and hit those awful, sour notes. The mistakes I make now are when my finger falls off a string or something.” He started out practicing scales “down at the bottom of the guitar,” he explained: “the seventh scale, the major scale, the minor scale, and the major seventh scale.”

The bottom line, he said, is that there are no shortcuts. “No man, there really aren’t any. It’s the old developing of the fingers thing. A lot of young kids start out being lead guitar players and consequently turn into terrible rhythm guitarists. One thing you must learn is how to be a good, strong, effective rhythm player, or you’re just out of it. You’re useless to anybody else.”

And when it comes to speed, Stills said he favors musicality over miles per hour.

“Playing fast is not necessarily best,” he added. “It’s what you play when. In a way, too, it’s a question of taste. I mean, the taste of the public could leave me right behind. But I’m basically a blues cat, and one well-placed blues lick can just rip your heart out. That’s the theory I work on.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.