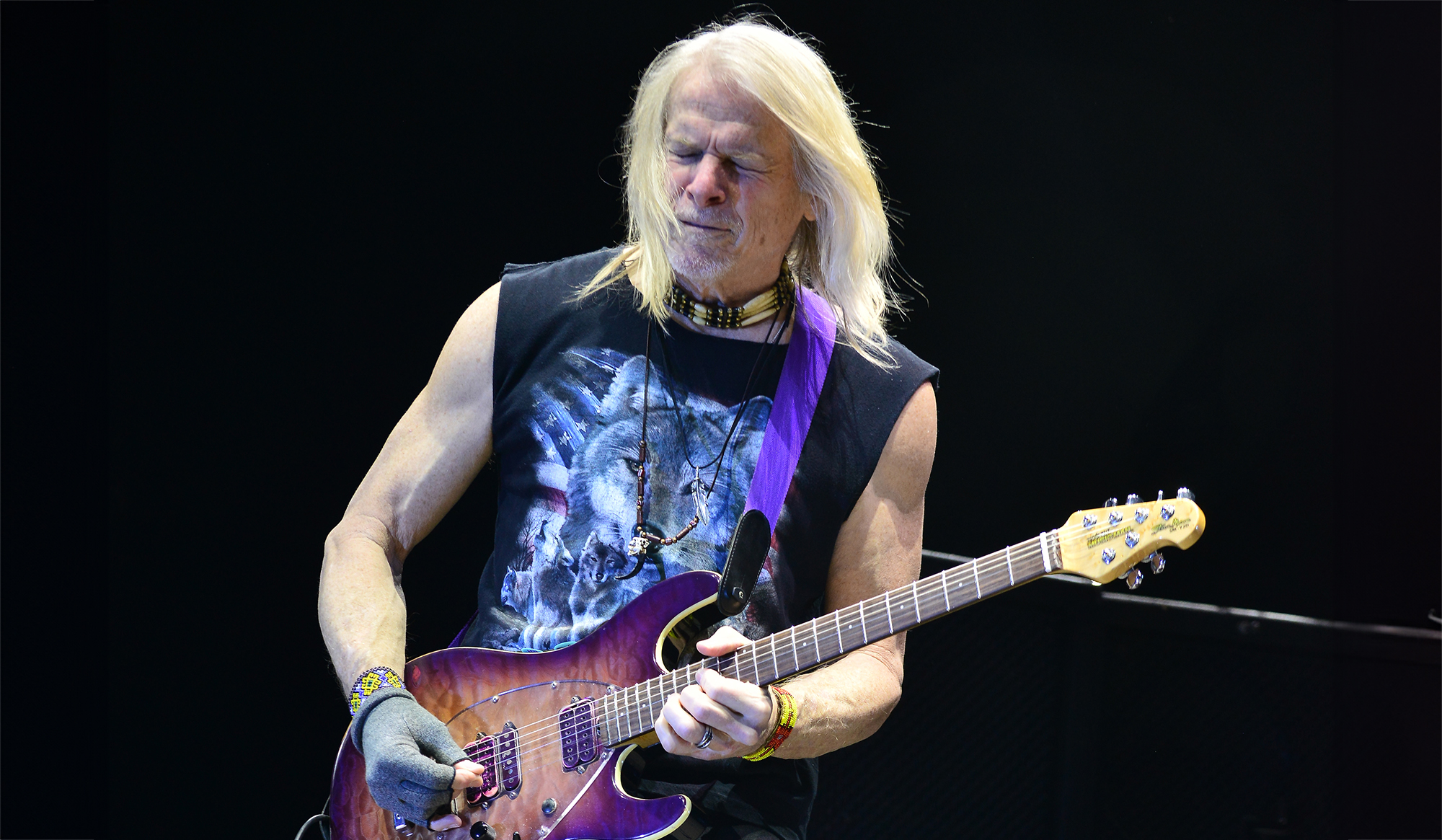

"Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, 'F*** everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up'?" Happy birthday to Ritchie Blackmore. The guitar legend looks back on his career in an interview from our December 1996 issue

The guitarist spoke about Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and his own infamously bad temper

This interview originally appeared in the December 1996 issue of Guitar Player under the title "Mistreated: Will Ritchie Blackmore Ever Get His Due?"

Deep inside a German castle, Ritchie Blackmore sits at a long table, dressed in medieval garb and clutching a goblet of mead. A group of minstrels skips into the dining chamber, playing a motley assortment of Renaissance instruments — crumhorns, sackbuts, rackets, regals, and hurdy-gurdies.

Transfixed by the otherworldly music and 16th-century setting, the Rainbow and former Deep Purple guitarist — a legend to thousands of aspiring virtuosos — experiences a sudden epiphany.

"This is what I want to do! I don't want to be plugged into a Marshall anymore!" he laughs, recalling the event later over a cold Beck's at a plush Manhattan hotel. "I actually said to them, 'Do you want a guitar player?' They said, 'No, we already have a lute player.' I was crushed."

It wouldn't be the first time Blackmore's been excluded from an elite musical club. While the trinity of Beck, Clapton and Page are roundly hailed as the Big Three of British rock guitar, mentions of Blackmore are usually reserved for the B-list, with a faint muttering about his infamous arrogance and a quip about "Smoke on the Water" inspiring 25 years of garage-band cacophony. Tell that to Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins. "Pound for pound, he's one of the best soloists in history," Corgan says, "but he's such a dick that he'll probably never get the credit he deserves."

Okay, so Ritchie's been less than enchanting to certain individuals over the years. Miles Davis was no milquetoast either.

The facts: Despite his protestations to the contrary, Eddie Van Halen — perhaps the most influential post-Hendrix lead guitarist of the late '70s and '80s — owes far more to Blackmore's vocabulary than he does to Eric Clapton's, his professed main influence. Think about it: Rapidly ascending or descending triplet patterns, aggressive pick dynamics and quasi-Spanish phrasing, diatonic neoclassical runs, a beady and compressed high-gain sustain, stacked fourth double-stops over meaty, open-hat grooves, shrieking whammy bar growls, a screaming singer — the basic seeds of shred were sown by Blackmore and brought to full bloom by Eddie's original renegade vision. Not even Hendrix turns up in Van Halen's post-blues metal the way Blackmore does, and that goes double for Yngwie Malmsteen, Steve Morse (Ritchie's replacement in the new Deep Purple), Vinnie Moore, Randy Rhoads, Michael Schenker and many others.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While the rest of England's future guitar gods were listening to Chicago blues records in the mid '60s, Blackmore had already studied classical technique, played with Gene Vincent and Jerry Lee Lewis, and was doing extensive session work with producer Joe Meek and the Outlaws. He was also woodshedding with records by Chet Atkins, James Burton and Cliff Gallup. He admired Albert Lee's fiery finesse and dug the ferocious chops and cool attitude of Gypsy jazz giant Django Reinhardt. Instrumental Deep Purple tracks like "Wring That Neck," "Lazy" and "Mandrake Root" were born of virtuoso guitar traditions that relied on motifs, syncopation and long runs — not just licks and turnarounds — that most young guitarists of the era simply didn't grasp.

With jazz-informed drummer Ian Paice, it's little wonder Purple swung relentlessly on live ' 70s albums like the historic Made in Japan, which effortlessly melds space rock, boogie, jump blues, rockabilly and MC5-style protopunk. Delivered with monstrous chops, passion and high drama, Blackmore's cascading sextuplets on "Child in Time" married country bop and jump jazz with a new brand of hard rock vocabulary, creating a blueprint for the next generation of an1bitious players. With Rainbow he'd push the classical connection even further, with epic tracks like "Sixteenth Century Greensleeves" snd "Stargazer.''

Blackmore may well deserve his reputation. He's a maverick, loner and practical joker who revels in gratuitous dissension. Claiming that singer Ian Gillan's attitude was becoming increasingly unprofessional and his voice "completely shot," Blackmore quit Deep Purple a year ago. (The classic Mark II lineup had re-formed in '85 and released several albums, including the excellent Perfect Strangers.) The 51-year-old has fired up Rainbow once again — albeit with completely different sidemen — on the new, heavily gothic Stranger in Us All, which delivers a refreshingly lyrical and laid-back lead approach.

In the market for a good 12-string, Blackmore, a fan of Adrian Legg and Leo Kottke, is also recording an acoustic album of Renaissance-inspired originals with his fiancée, Candice Night. Articulate, circumspect, and soft-spoken, Blackmore's a true eccentric who holds regular séances at his Long Island home, "practically lives" at Renaissance fairs, and maintains a surprisingly humble, even insecure, attitude toward his own electric guitar legacy.

"Music is an intangible force," he says as the lobby clock strikes midnight. "I'm still trying to master it, so telling someone else my views is like the blind leading the blind."

You have a long-standing reputation as being difficult and hard to work with.

My whole thing comes from Django Reinhardt. He's my hero, not just because of his playing, but because he was such an awkward bastard. It was brilliant how he would be scheduled to be onstage, and he'd still be in bed in a local hotel. And when they'd go to the hotel to get him, he'd have 20 people in the room with campfires going. He'd get paid an exorbitant amount and then take a taxi from Paris to Lyon, which is hundreds of miles.

Reading about that was so refreshing. I hate show biz. I hate people who confine themselves to the system. Why does everyone have to do the right interview at the right time, be on the right program, be politically correct, say the right things and be at the right parties? That gets up my nose. Why can't I just play the guitar? It's all I want to do. Why do I have to be in this video? Why do I have to say nice things to the record company president? Why can't we have more Django Reinhardts going, "Fuck everybody. I'll turn up when I feel like turning up." It's unfortunate that people like that usually end up penniless, compared to all the not-so-great musicians who know how to manipulate the music business and take it for everything it's worth.

Does it bother you that you're not given the same credit as Beck, Clapton, or Page?

No. I'm an introvert, as my father would say. I tend to be very withdrawn. I don't sell myself. I don't think Jeff Beck does either. I think Jimmy Page does and Eric does. They tend to push themselves out there a bit more, although they're all great people. A lot more falls on Eric because he can sing well, and Pagey is such a great writer and producer. Jeff is probably one of my favorite players. This man just hits notes and you think, How come that note's not on my guitar? And he gets this incredible sustain for no reason. He's so fresh, so un-show business. That's what I love about Jeff.

With all due respect to Page, I've always felt that Zeppelin was never as strong a live band as Purple, mainly because they didn't swing.

I agree with that, because Bonzo wasn't a swinging drummer. He was very good, but he was a lead-footed drummer. Ian Paice is a swing-type drummer, a jazzy, Buddy Rich-type drummer — skip-bop-bop-bop-bop. Also, Jon Lord was very inspired by Jimmy Smith and Graham Bond, who was the big thing in English jazz at the time.

You were one of the first rockers to play very long lines.

That's an interesting point. Pagey once asked me, "Where do you get all those runs from?" I developed it from Les Paul, Jimmy Bryant, Chet Atkins and Wes Montgomery. I wasn't listening to rock when I started out. The Beatles were around, but no one took that seriously — except for billions of record buyers! They're still a great band, but you couldn't learn anything instrumentally from them — pretty little tunes, though.

I was very into country music from '63 to '66: Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West, Chet and Don Rich, the guitarist from Buck Owens and the Buckaroos. In fact, when I first came to America in 1968, I thought it was a bit like taking coal to Newcastle. There are so many good players over here, why are we going to America? When people would tell me I played really well, I'd say, "You've got all these guys in Nashville who could burn me off the face of this earth." The response was, "Well, we don't listen to those people." Why not? "Well, that's country. They don't play rock."

Chet Atkins was my big idol. I used to try to copy his stuff. Back in '64 I learned Jimmy Bryant's "Arkansas Traveler." I played it for people just to show off. And of course I loved Gene Vincent's guitar player, Cliff Gallup, who was just phenomenal — another creative man who didn't play by the rules."

Who were your favorite blues players?

Shuggie Otis was the best player I’d ever heard. His father was Johnny Otis. He was only 14 at the time that he played most of his great solos. He had a very similar style to Mick Taylor, another favorite of mine — never throws away a note, and always that vibrato. I get a little lazy with my vibrato sometimes. It’s easy for me to play fast. I have to tell myself to slow down and say something: “Don’t just exercise, and remember the vibrato.” I always find that a good vibrato, like a B.B. King vibrato, is much easier to play, whereas a slow vibrato is more difficult. So I go for the slow vibrato just to punish myself.

Were you and Albert Lee friends or competitors in London in the ’60s?

I couldn’t compete with Albert — he was too good. I met Albert around 1962, the first time I went to London when I was around 16. I was a local boy from a very quiet village called Heston; I’ve since found out that Jimmy Page is from Heston, but I didn’t know him then. I’d never been to a nightclub before so I was a bit overwhelmed. The Ricky Barnes Band was playing, and their guitar player was Albert. He was playing a black Les Paul and he was just incredible. I didn’t know where his notes were coming from. It was such complicated, tasteful, brilliant stuff. I was like, “Oh, dear. If this is what I’ve got to compete with, I might as well hang it up. It’s all over.”

He was only a year older than me, so I was devastated. I went home with my tail between my legs. Luckily, not too many people played like Albert. I got friendly with Albert after a while, and I did an LP with him and my old teacher Big Jim Sullivan called Green Bullfrog.

Were your parents supportive of your career?

They were very supportive. When I was 11 years old, my father said, “I bought this guitar for you, and if you don’t learn it, I’m going to smack it across your head.” He sent me to lessons and said, “You’re going to learn to do this properly.” It was strange because the teacher was teaching me things like diminished and augmented chords, and I couldn’t even play a major chord yet. I was like, “What’s this all about? I just want to strum a guitar and show off. I don’t want to know about diminished chords.”

My dad worked at the airport as a draftsman, and he was very analytical. My mother was completely the opposite: “Just let him have fun.” My father helped me out in learning the guitar, because he was so mathematical. I’d say, “Dad, how do you play these notes?” He didn’t play an instrument, but he would work it out for me.

Do you still scallop the frets on your Strats?

Up to about the seventh fret, I sandpaper the frets very little. But up to about the 15th fret I get quite deep. Actually, I have two Fender Custom Shop models coming out. One of the models is something I designed myself. The whole thing is solid, not separate neck and body. I believe that the guitar resonates much better that way. It has two pickups, not three, very big frets and a scalloped neck. A lot of Fenders have such thin frets — very spidery. My neck will be one and a half inches at the nut and two inches at the 12th fret. Fender was telling me that Yngwie’s model doesn’t sell very well because of the scalloped neck. I said, “Yeah, but if we’re going to make a Ritchie Blackmore model, it has to be scalloped.” So they reluctantly scalloped it a bit, though I scallop it quite a bit more. But the result is very close to what I like.

Are you still a devoted Marshall man?

I use Engl amps now, built in Austria, and I have my own Ritchie Blackmore model. I first tried one when I needed a small amp to play with my friends, and I couldn’t believe how good it was. I asked a roadie of mine if we could get a deal, and he said, “No, the guy’s not interested in a deal. You’ll have to pay full price.” I was like, “I’m not going to pay full price for it.”

But after playing with it for a month, I said, “Okay, okay, I’ll pay full price.” That’s what I use on the entire new LP. And the head is only 50 watts. I was so sick of playing through my 280-watt Marshalls.

What’s the story behind those souped-up heads?

I wanted to use Marshall amps because they looked great and Jimi Hendrix and the Cream played them. At the time, I was still using a Vox AC30 with my Gibson 335. I knew Jim Marshall as a drum teacher who used to teach Mitch Mitchell, who, incidentally, worked in Marshall’s shop — Marshall’s of Ealing, near London. Pagey used to go in there a lot too. I told Jim that Hendrix using his amplifiers would make him huge worldwide. He said, “Hendrix — he’s the guy with the afro, right? Yeah, he’s doing well.” It didn’t quite click in. And Hendrix was paying for those amps, as were the Cream.

Ken Bran was the guy that really built the amps — Marshall just designed the speaker cabs and the look. I said to Ken, “I want to hear this really loud — that’s how we play.” He took me to a soundproof room, but it was still so loud that all the people on the assembly line—about 50 of them — would stop working and complain to Jim Marshall, “We’re not working with that racket.” I’d be playing for hours: “More treble!” Ken would literally be there with a soldering iron, taking out resistors. “More bass!” I told them I wasn’t happy with the sound. “There’s no sustain in your amps — no body.” “They’re good enough for Hendrix and Clapton.” “Yeah, but I want some sustain.”

I knew a bit about amplification. I used to work in radio at the airport. I told them that what it needed was an extra output stage, so they built extra output valves into it. After a while they explained that my amp was now 280 true watts, not American watts. This is equivalent to 600 watts.

Of course they said, “If anyone comes in here and asks for a Ritchie Blackmore amplifier, we’re going to tell them it’s stock Marshall, because we never want to do this again. You’ve put us through hell!”

Do you always solo with the neck pickup?

No. I change my settings probably 20 times during a solo. I like the inflections of different pickups. I’ll whip back the toggle switch to the treble pickup within one second of getting into a solo, and then back again.

Your sound is always so fat, though. It has the character of a single-coil, but the weight of a double. Is that just a function of cranking your amp?

It’s my preamp, which is an old souped-up Aiwa reel-to-reel tape recorder that I originally used as a tape delay. I had it lying around the house in 1970 and I thought, What can I do with this? In those days you made everything count. It has an input and output stage, so I plugged into it and noticed that it gave me a fatter sound—about a three-watt boost. I used it from that day on. If I don’t use it, the sound is too shrill. It seems to calm the sound down and get more midrange. It drives people nuts on the road — it breaks down all the time because it’s so antiquated.

I had a new one made to identical specs, but I could hear a difference. That’s the sound I’m used to, and I find it very difficult to play without it. I just thought it was a normal tape deck, but now it’s become this little soul on the side of the stage. It’s like my little friend. It waves to me. Nobody would dream of having that today. “Hey man, you could have 14 pedals that do that.” “Yeah, but are they old souls?”

A former editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, and an ex-member of Humble Pie, Mr. Bungle and French band AIR, author James Volpe Rotondi plays guitar for the acclaimed Led Zeppelin tribute, ZOSO, which The L.A. Times has called “head and shoulders above all other Led Zeppelin tribute bands.” Find JVR on Instagram at @james.volpe.rotondi, on the web at JVRonGTR.com, and look for upcoming tour dates at zosoontour.com