"Very few people can play fast and put feeling into it. A lot of it is just cold technique…" Peter Frampton: The Guitar Player Interview

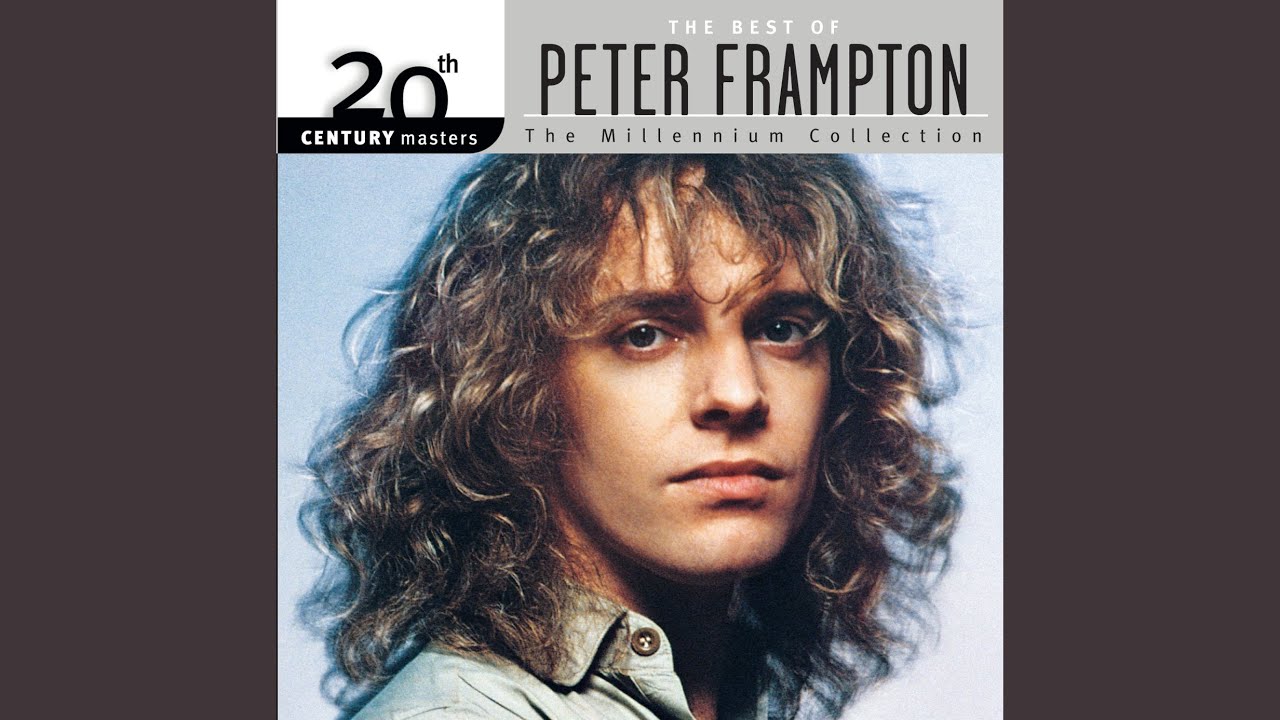

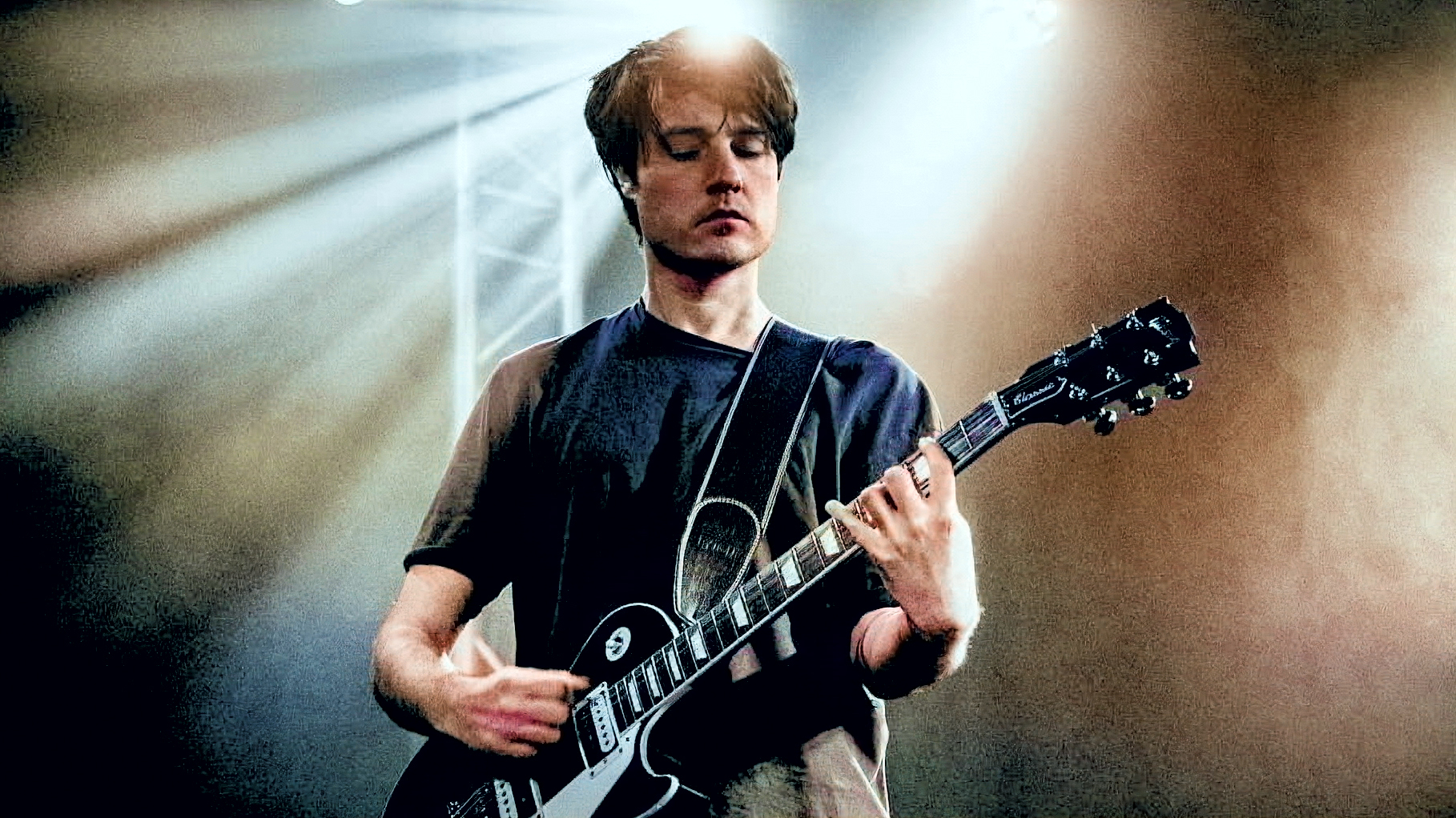

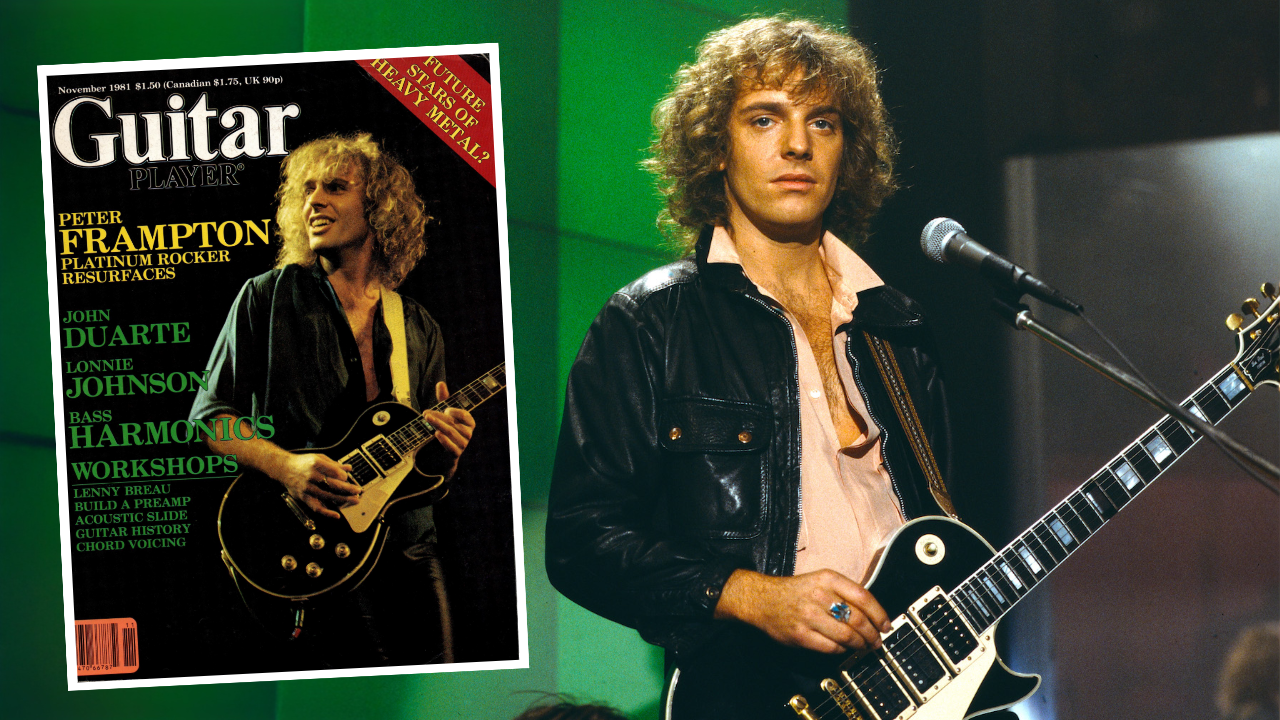

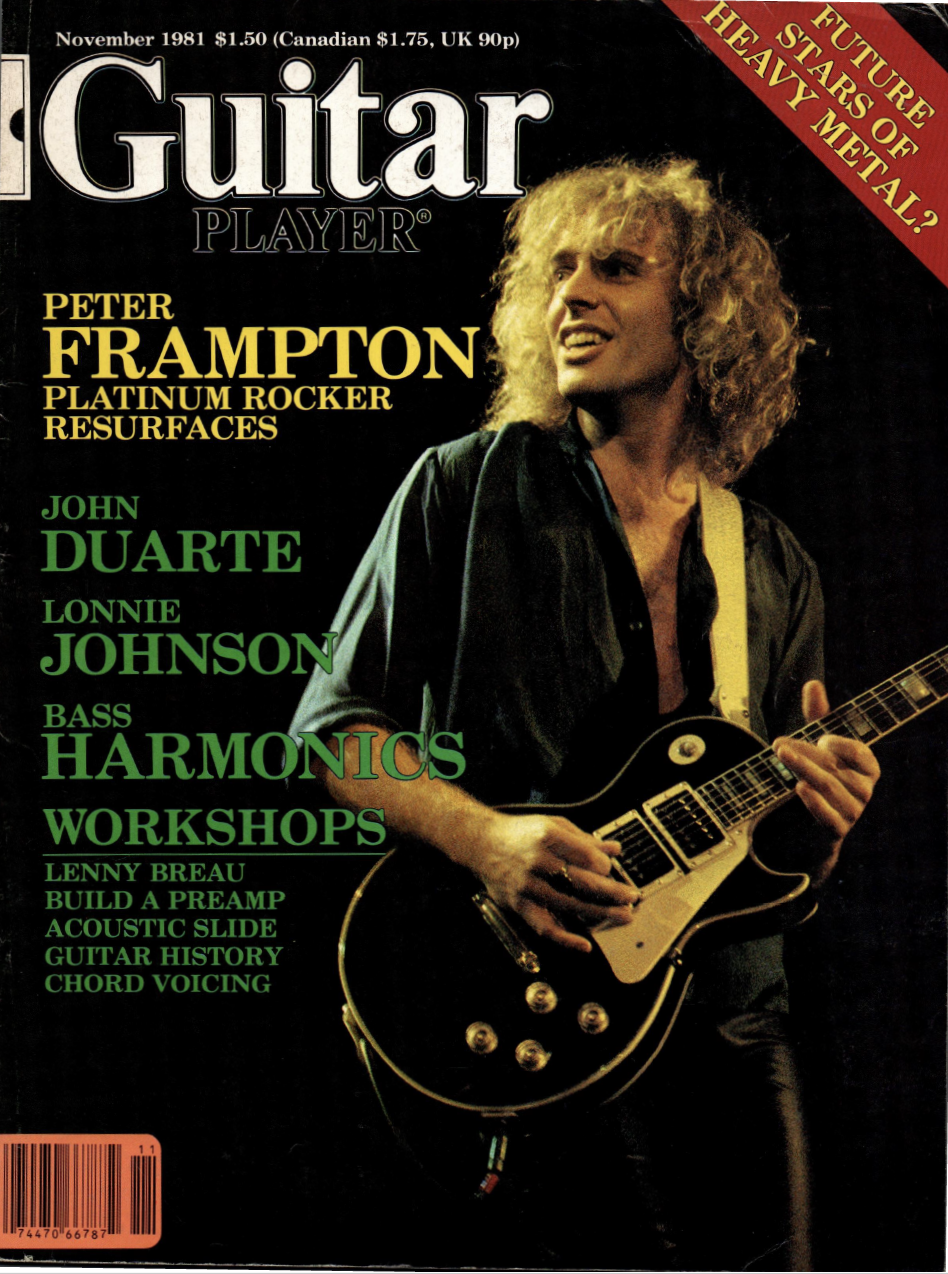

Peter Frampton turns 75 this week. Back in November 1981, we sat him down for the ultimate guitar interview: technique, gear, 'Framptortion' and the – ulp! – Sgt Peppers movie

Peter Frampton turns 75 this week. In tribute, we've delved into our archives to find this Guitar Player exclusive from November 1981. As the intro explains, Frampton had come a long way in a few short years: from a respected songwriter and guitarist with Humble Pie, to a huge international pop star with Frampton Comes Alive, to critically-panned albums and a part in the disastrous 1978 movie Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Luckily, this period would pass too. Guitar Player caught him in fine mood, able and willing to talk about every facet of guitar playing.

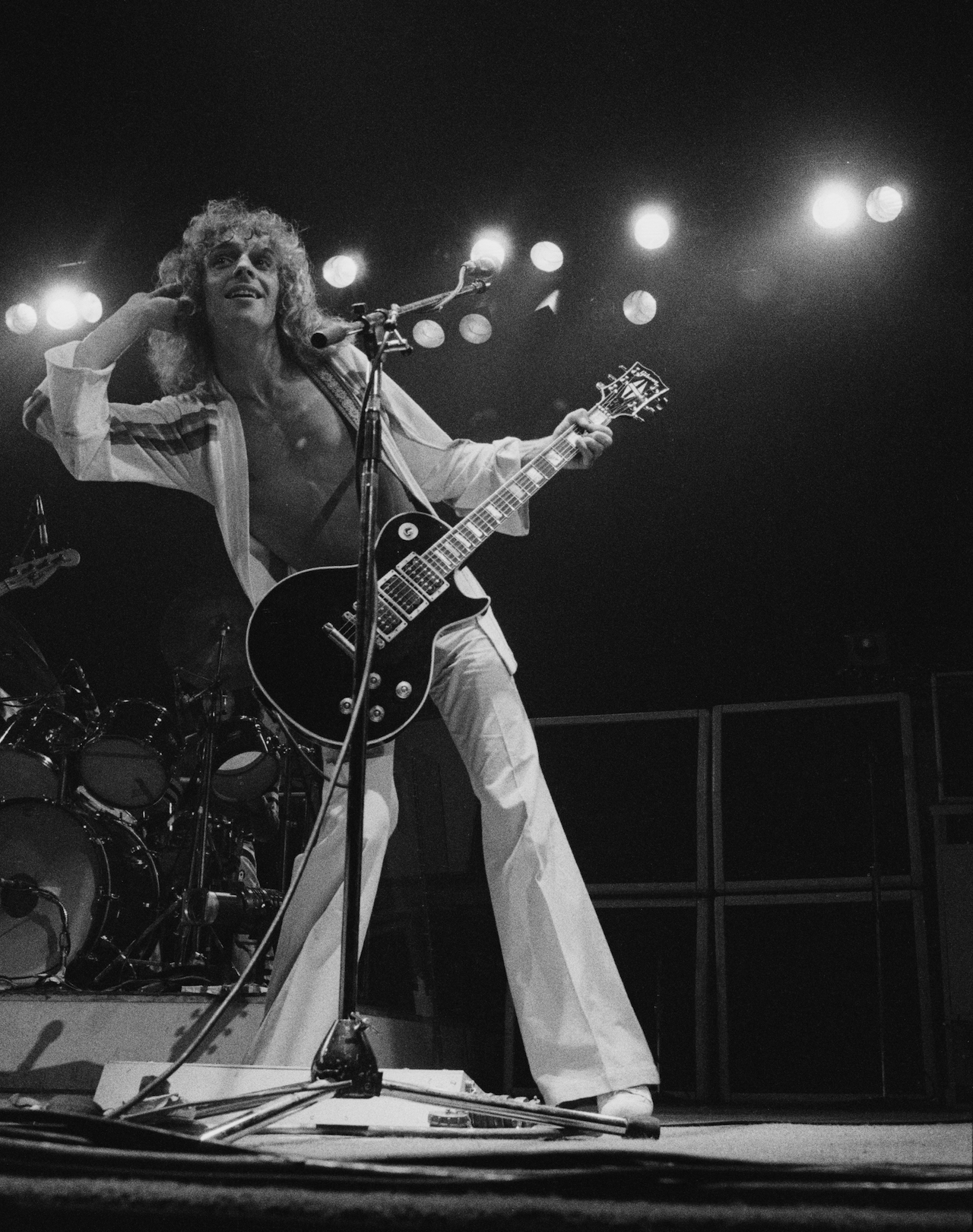

Peter who? Before the monumental success of Frampton Comes Alive in early 1976—at the time the largest-selling double album in history, with over 12 million copies on the world's turntables—the photogenic British guitarist Peter Frampton was hardly a household name.

He had enjoyed moderate success with the Herd, Humble Pie, and Frampton's Camel, and had released three solo albums. But 1976 was the year. Frampton Comes Alive was not only Peter's first gold album (sales exceeding 500,000 copies), but it quickly soared far beyond platinum (sales of 1,000,000); the numbers were even more staggering compared to sales figures of only 200,000 for any of his previous efforts.

After more than seven years of practically nonstop touring, albums that didn’t score major hits, and a lot of personal expense to keep going through lean times as a second-bill act, Peter Frampton suddenly had millions of people singing along with their radios and stereos as he rocked through songs like “Show Me The Way” and “Baby I Love Your Way”—songs that were practically ignored when they were released on his studio albums.

After reaching the pinnacle of rock stardom, Frampton found his life became never-ending confusion. Pressed to duplicate his live-album success, Peter recorded two albums—I’m In You and Where I Should Be. Neither matched the impact of the live LP, although I’m In You did sell over 2,000,000 copies. By and large, critics panned both albums, and many proclaimed him washed up and out of ideas.

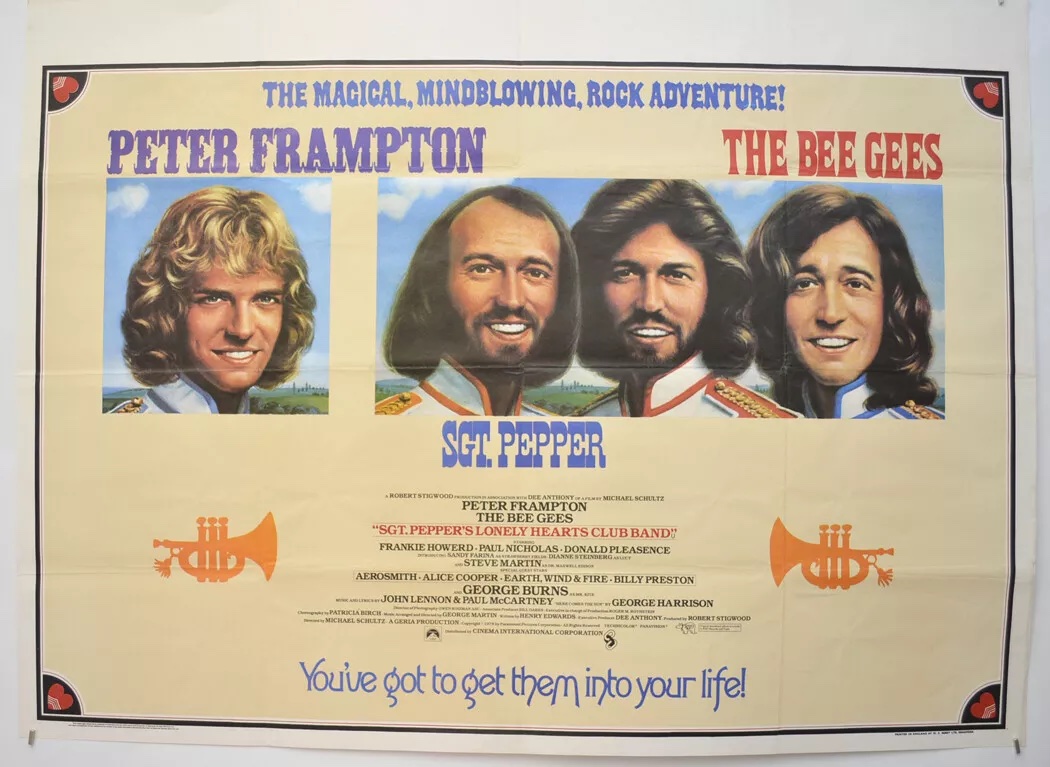

Legal hassles—including a “palimony” suit brought against him by his former girlfriend—a car wreck in the Bahamas, and a split with his longtime manager further complicated his life. The 1978 movie Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, in which he and the Bee Gees co-starred, was a flop with critics and the public alike, despite the cast’s popularity.

In only a few short years, Frampton had fallen from grace—not just with the media, but with many of his fans. The crash of a plane carrying his equipment—including his famous triple-pickup black Les Paul—on his 1980 South American tour seemed like just another blow. But he wasn’t finished yet.

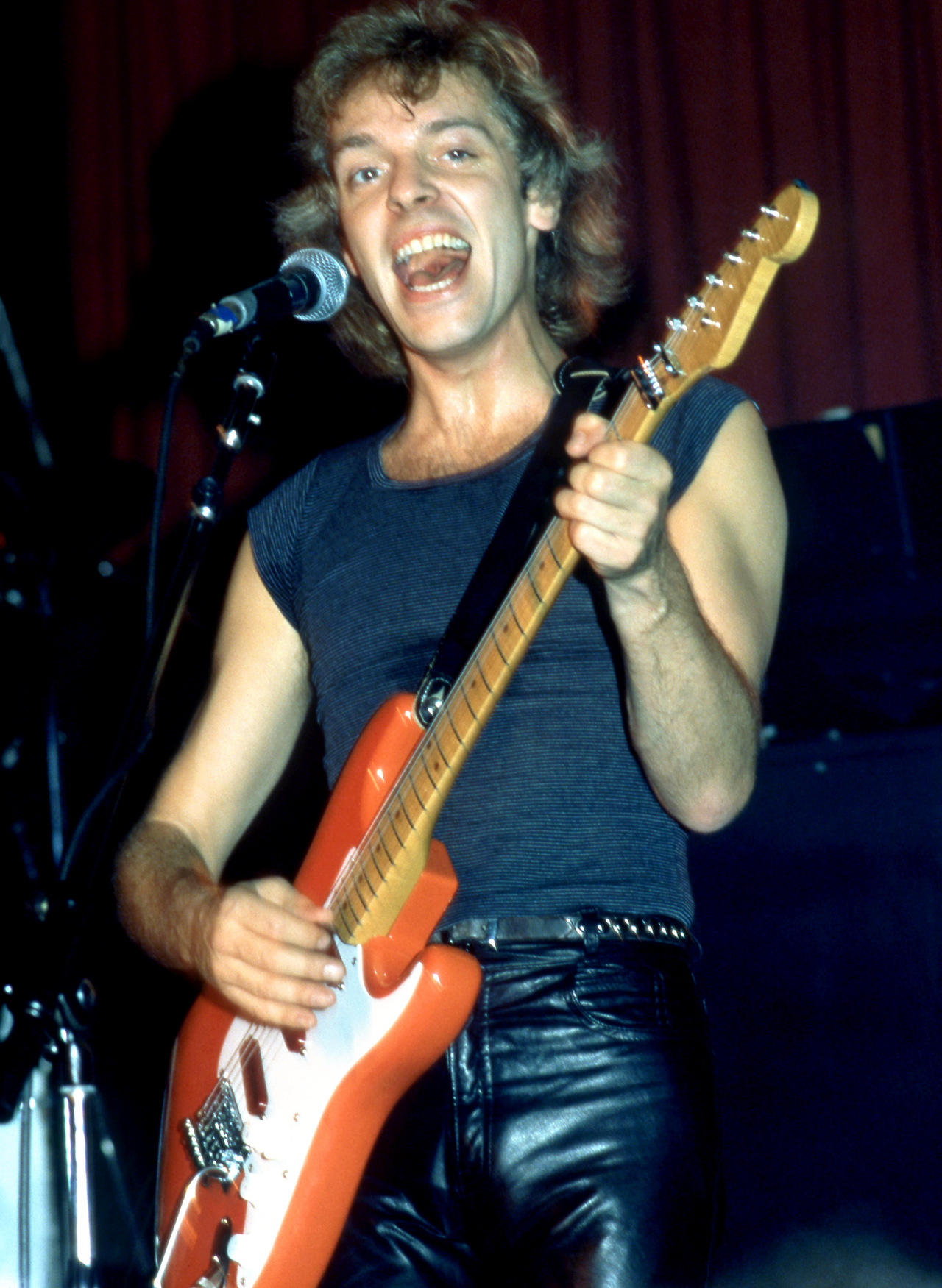

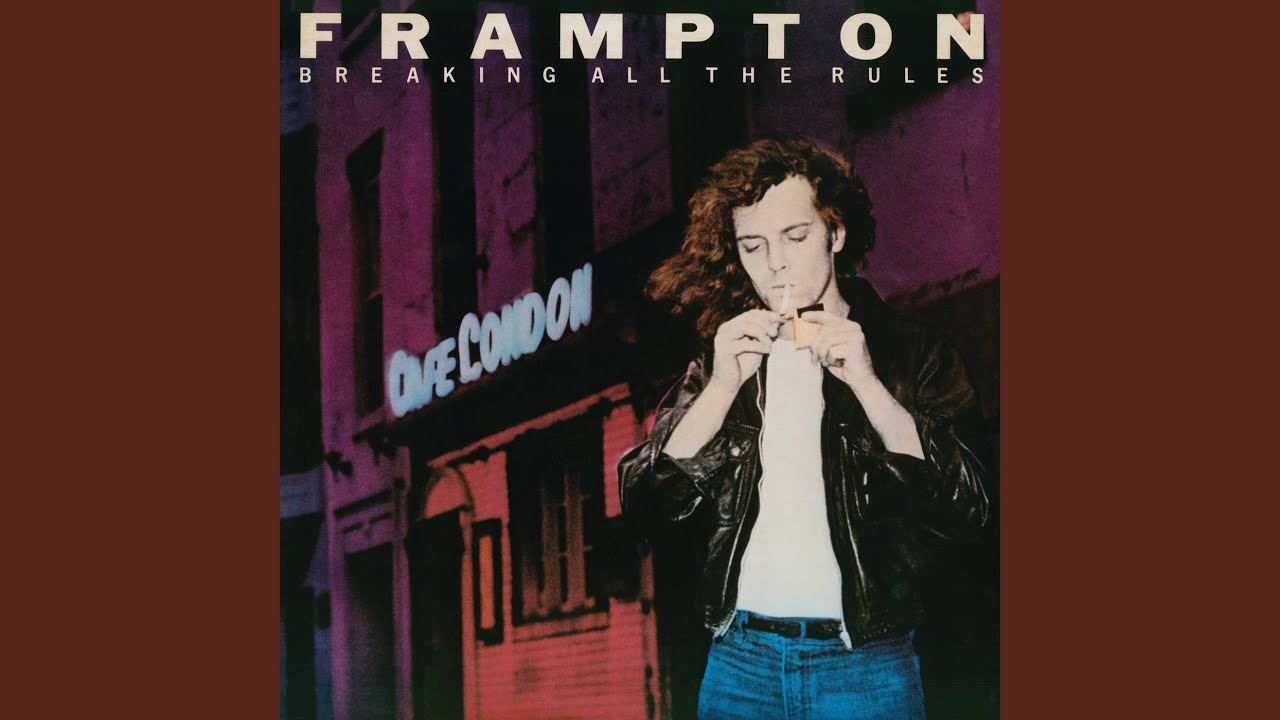

Although he has kept a low profile for the last year, Frampton hasn’t just been sunning himself. He’s been writing new songs, regaining his chops, and plotting a new direction. No longer content to be seen as a pop star who happened to play guitar, Peter picked himself up and recorded a heavily guitar-oriented album entitled Breaking All The Rules.

Joined by Toto’s guitarist Steve Lukather and drummer Jeff Porcaro, as well as keyboardist Arthur Stead and bassist John Regan, Frampton set out to create as live a sound as possible while recording in a studio. (Still committed to their work with Toto, Lukather and Porcaro were later replaced by Cretones guitarist Mark Goldberg and studio drummer David Kemper.) The band—affectionately dubbed “Froto” by the road crew—set up on the Chaplin Stage at A&M Records’ facilities in Hollywood. Built in 1919 by comedian Charlie Chaplin, the cavernous room was ideal for creating a live feel. In just over a week, the basic tracks and most of the overdubs were recorded—the shortest it has ever taken Peter to record an album.

His guitar work is the most aggressive it’s been in years, and the songs aren’t as sweet as on his last two albums. Now, at 30 years old, Peter Frampton is embarking on a new career of sorts—that of guitarist. But that’s what he’s wanted to be all along.

Since before he was eight years old, Peter Frampton, who was born in Beckenham, Kent, on April 22, 1950, has played the guitar. From his first bands and four years of classical guitar lessons, he knew he wanted to be a guitarist. At 16, he was touring with the Herd, who had hit singles in 1967 and ’68 such as “From The Underworld,” “Paradise Lost,” and “I Don’t Want Our Loving To Die.” After touring Europe with the Herd for two years—and being singled out by the press for his pin-up good looks—Frampton started Humble Pie with former Small Faces guitarist Steve Marriott.

From 1968 to 1971, Humble Pie (which included bassist Greg Ridley and drummer Jerry Shirley) produced five albums. Their most successful was a live LP, Performance—Rockin’ The Fillmore, which perhaps foreshadowed Frampton’s own live success nearly five years later.

In its short life, Humble Pie had shifted from eclectic beginnings to becoming an almost exclusively heavy metal outfit. Seeking musical elbow room to expand his playing and songwriting, Frampton left to pursue a solo career. Over the next year, he worked as a session musician on albums for George Harrison, Harry Nilsson, and John Entwistle, as well as on jingles.

In 1972, he recorded his first solo LP, Wind Of Change, featuring session players including Klaus Voorman, Nicky Hopkins, Billy Preston, Jim Price, Bobby Keys, and Ringo Starr. Though Wind Of Change and his next albums Frampton’s Camel and Somethin’s Happening saw modest sales and no major hits, Frampton persisted, touring relentlessly.

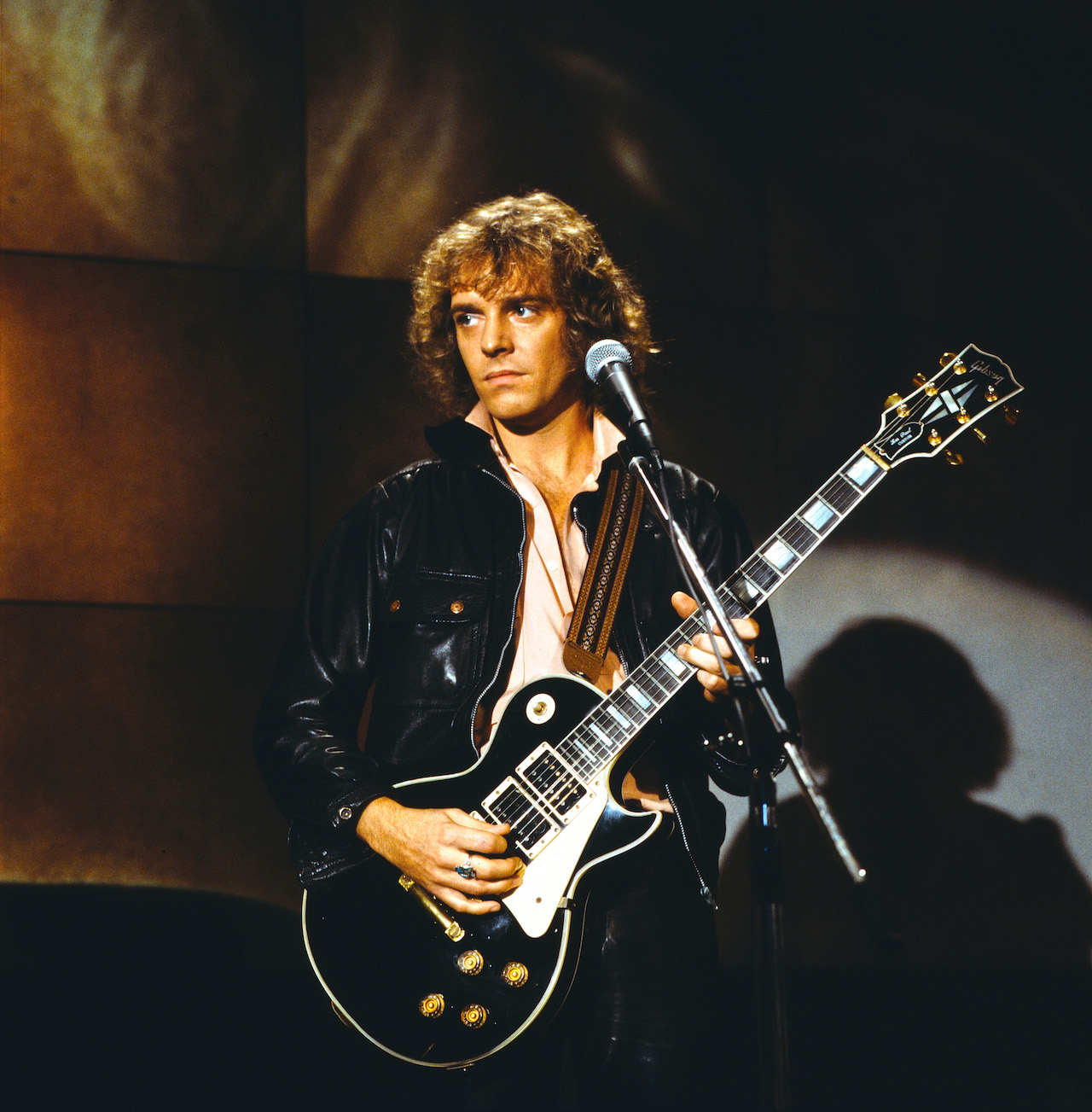

By 1975, his fourth album Frampton featured a single called “Money” that did well, and his album sales picked up. Thanks to his persistence, he began headlining with his band—bassist Stanley Sheldon, guitarist/keyboardist Bob Mayo, and drummer John Siomos. Soon after, Frampton Comes Alive would bowl the rock world over, and the Les Paul–toting blond guitarist would finally become a household name.

What motivates you to play the guitar?

That’s sort of an easy question. I’ve been doing it ever since I was about seven-and-a-half, and it’s the one thing I don’t think I’ll ever stop doing. I go through phases where I play for hours and hours, and then I take a break. But basically, I think it’s something I couldn’t live without.

Have you considered turning to producing instead of playing guitar?

Don’t get me wrong—I’d love to produce other people. But ten years down the line, I still see myself playing guitar. There have been times since the live album came out where I didn’t really want to even look at a guitar because I was working so much. But when things slowed down, there it was—that old guitar staring at me. I play other instruments, but the guitar is what turns me on the most, and I’m sure it always will.

Last year, many of your guitars were destroyed. What happened?

At the end of the South American tour in October and November 1980, we were going from Caracas to Panama. Since no 747s or big jets fly that far south, we didn’t fly with the equipment. It had to be shipped separately on a cargo plane. While we waited in Panama, reports came in that the plane nose-dived, split in two, and caught fire.

How many guitars did you lose?

About 12 or 13. Luckily, we didn’t take everything. I lost my black, three-pickup Gibson Les Paul, a couple of basses, Ovation acoustics, other Les Pauls, and my red Stratocaster—the one I called my “Show Me The Way” guitar. [Years later he recovered it: read the full amazing story here.]

But from this experience I learned that those guitars were just old favorites, and I was just in the habit of playing them. When those went, I realized that I had to go out and do the big search to find other favorites. There are some great guitars around that I'd never played before, so in a way there was a good side to it.

So, which are your main guitars now?

Well, I always wanted a '59 or a '60 sunburst Les Paul, and I found one. Frank Lucido at California Guitar very kindly did a search and found me a beauty. I play that most of the time. Seymour Duncan, who's helped us an incredible amount, knew that I was looking for a Les Paul and a Strat, or anything that would tide me over. So he came over to see me; he brought this old plastic guitar bag on his shoulder and pulled out what we call the Frankenstein guitar: It's sort of a Seymour-ized Stratocaster. No one really knows how old it is or exactly what it is, but he's put various bits together, and it's a honey. Since I lost everything, I've made so many friends in the business of guitars and electronics. It's amazing.

Have you replaced the black Les Paul that had become your trademark?

Yes. Gibson recently laid a black Les Paul on me because they were so sad for me that I'd lost the baby. And my roadies sort of configured it into a three-pickup, so it's almost like my old one. And while I was out on the West Coast, I picked up a real '59—an original three-pickup Black Beauty. My old three-pickup Les Paul was originally a twopickup with soap-bars—a '54 or '55 that somebody else put three pickups on. So it wasn't really original. This one I have now is the real thing.

[Ed. Note: "Black Beauty," a term not officially adopted by Gibson, is often applied to stock black Les Paul Customs, both two- and three-pickup models. "Soap-bar" is slang for Gibson's plasticcovered P-90 single-coil (non-humbucking) pickup.]

Are you using any newer models?

Not really. I tried a lot of new ones, and although I wouldn't put myself in the class of being a guitar collector at this stage, I am very fond of the old originals. If need be, I put either Seymour Duncan pickups in for an authentic sound, or sometimes I'll go the completely opposite way, which is to use Overlend EMG pickups.

Is this to get a really clean sound?

Right: But they've recently come up with some copies of '54 Strat pickups which are not that clean. So, for a couple of Telecasters that I have, they made humbuckers to put in the neck position, and single-coils to be located at the bridge. The sound will floor you! It gives just the right amount of breakup when you need it, or it can be very clean.

Having a couple of vastly different guitars like the Strat and the Les Paul, do you find that one is better suited for creating certain moods than the other?

Yes, I think that the Stratocaster obviously doesn't have the depth of the Les Paul, although there are exceptions. There's a lot less bassiness with a maple-top, such as my '59 sunburst than, say, an old Black Beauty. It's definitely got more highs, due to that maple top. But the sunburst is still a long way from a Stratocaster.

In general, are you most inclined to use the Les Paul?

Yeah, I think so. I was always into a very mellow sound. But I'm using a little bit more of the Strat than ever before. Basically, though, I use the Telecaster and the Les Paul, and I use the Stratocaster for one number— "Dig What I Say." When we're recording, I use them equally, because I love experimenting with different sounds and effects.

Do you have any doublenecks?

One guitar that we lost in the crash was a month-and-a-half-old double-neck built by Ed Monteleone, who's my guitar tuner and guitar maker. He made this double-neck Stratocaster for me with a mahogany body—to keep it light—Mighty Mite necks, and a double EMG pickup system. It didn't even have a finish on it yet when we took it out with us. So Ed made me another one, which is a work of art.

Why did you want two 6-string necks?

I sometimes write songs using open tunings, so when I play a song in open tuning, it's nice to be able to do the rhythm part on the bottom, open-tuning neck. And then when it comes time for the solo, I can play on the other neck, which is in standard tuning.

Do you amplify that guitar in stereo?

No. I was going to, but I cut down: I'm only using one Marshall now, whereas I used to use two. Basically, I'm trying to keep the stage level down a little bit. It's difficult not to turn up when the band sounds hot [laughs], but it gets exciting when you do. My basic system now is a 100-watt Marshall through a 100-watt cabinet with four 12s. The amp has been modified by Tony Frank, who I believe came up with the Marshall Mark II design, although he's no longer with Marshall.

What did he do to your amp?

He took it out of its cabinet, turned it upside down, and pulled out his little bag of tricks; I couldn't tell you what he did exactly. He snipped something here and put something there, and he asked, "Do you like this?" And I said, "Yeah. What else can you do?" Then he'd do some more and say, "Do you like this?" And he sort of customized a Marshall exactly to my taste. All these years I've been playing Marshalls and I didn't realize how good they were until he got out of mine exactly what I've always wanted to get.

Can you describe just how the sound is different?

Well, I'm using two inputs—they're now wired together—and a master volume. Tony gave me a middle boost as well. One channel sounds the way I always made the Marshall sound, and the other sounds sort of like a Fender. Now I can get some harmonics you don't usually get. It's a very full and rich sound with lots of top and lots of bottom.

The thing I used to not like about Marshalls was the fact that if you linked both channels together, the number 1 input was incredibly trebly. We knocked down the treble a lot, so I could balance the two inputs for a much smoother sound.

What do you think plays a greater part in creating your individual sound—the amp or the guitar?

I would have to say it's a combination of both, and also the way I hit the strings. I say this because a lot of people have played my guitars, but they sound totally different, even when they use the same settings. For instance, Ed Monteleone uses a thumbpick and fingerpicks, and he gives it much more of an attack when he plays it. Other people don't hit it as hard as I do, and it sounds mellower. So I think it's a combination of all three factors: your touch, the guitar, and the amplifier.

Do you have any preference of fingerboard materials?

Well, on the doubleneck we used ebony, and I love that. I mean, I think it's the first time that I've really known that I was using ebony, because I've only recently gotten into what necks and bodies sound different. We do a lot of experimenting with different electronics and things like that on different guitars to see what woods sound like with different pickups. But as far as necks go, my Frankenstein Stratocaster has a maple fingerboard. I also have a couple of Fernandes Japanese Strat copies, some with rosewood and others with ebony. So it's difficult for me to say which ones I like best because each guitar feels so different anyway. My Gibsons all have their stock fingerboards; I accept Gibsons the way they are.

Have you done any comparisons of different necks on a single guitar?

I've not done an A/ B comparison on, say, the Frankenstein to see what it would sound like with different wood. I tend to be more concerned with the shape of the neck than its material. I'm not a thick-neck person, because I have very small hands. So on a Strat, I really like the old "V"-shaped contour—that's really nice. And I have my own dimensions for my Les Pauls. We measured the dimensions of the neck on my '59 sunburst, because it was perfect for my hand, and shaved the necks of other Les Pauls to the same shape.

Are there any modifications that you automatically have done when you buy a guitar?

Well, usually, if the nut is not already brass, I have it replaced. And depending on the age and quality of the tuning pegs, I'll change them. But sometimes I like to leave as is, like on my '59 'burst—I've left everything stock. I haven't touched a thing, because it's perfect. On Strats, you get to the point where things are so rusted-up around the bridge area that it's good to put a new tailpiece on. I also put five-position switches on my Strats.

Do you prefer Strats with a vibrato or without?

I'll take them either way. When I started playing, I was into the Ventures and the Shadows, and everything I had had to have a Bigsby vibrato. I never had a Strat when I was doing all that. It was always a Guild, a Hofner, or a cheap Gibson. I always used tremolo. Now, on the double neck we didn't put any tremolo arms on because we were concerned about the weight. The Frankenstein, however, does have a tremolo arm, which is very well weighted and is very, very smooth—easy to work. I treat some guitars differently according to their appeal as well.

For example, I have a teal blue •Stratocaster —a pretty old one with its original color— but that dame stock with no tremolo arm. I love it as it is, and wouldn't want to change it.

Do you put jumbo frets on your Strats in order to make them feel more like your Les Pauls?

Not necessarily. It depends on what shape the frets are in when I get the guitar, and how it feels. Some guitars you don't want to change; some you do.

Do you do anything unusual with the vibrato bar?

I'm using that a lot on my Strat, like on "Dig What I Say." I love it. Jeff Beck has wonderful technique, because he also uses the talk box. There are some nice effects from putting the Strat through the talk box and then bending the notes all the way down; it's really effective. I've been thinking about putting a synthesizer guitar through the talk box as well, because that'll be really interesting. I've tried actual keyboard synthesizers through it. I overdubbed several ARP Axxe keyboard synthesizers with talk box on "Putting My Heart On The Line". When you've got a constant note, it's easier to talk and do whatever you want to do. You get weirder effects. The synthesizer guitar should behave in virtually the same way because it sustains almost as long as you want it to, and with guitar technique, it will be very good.

Have you had any type of clamping mechanism installed on your Stratocaster to keep it in tune?

Not yet, but I'm having a Strat put together with a new system made, I believe, by the Japanese. Each tuning machine has its own individual clamp. If you go berserk with the vibrato, the tuning is naturally going to leave you. But if you have the vibrato set up right, and have it looked after, you won't encounter too many problems. Obviously, if you've got new strings and you go berserk without stretching them, you'll have lots of problems. But right now, I'm not having too much trouble at all.

How many springs do you have in your vibrato mechanism?

Just three. I tried it with five springs, but then it's much more difficult to use. I like a really easy response, so we took two springs out of every Strat that I have.

What kind of strings do you use?

I use either Ernie Ball or Dean Markley stainless steels. I'm not into all the gauges, but I think the set goes from .009 to .042. I used to use .008s for the high E until about a year-and-a-half ago. Then I realized that I was missing out on a lot of frequency response. The .009 gives a fatter sound. I was accustomed to using .008s—they were Picatos, which are made in Wales. My road crew got me to change to a heavier gauge because the lighter ones never stayed in tune as well.

Do you have them changed very often?

It depends on how much the guitars are used. If I use a guitar like my Les Paul sunburst for more than six or seven numbers each night, then they get changed every night. Otherwise, I'll leave them on for two or three nights.

What kind of pick do you use?

It's a copy I have made specially for me. I used to use these small, thick, teardrop-shaped Hofner picks that didn't bend at all. They were about a sixteenth-of-an-inch thick. Hofner stopped making them, and I saved the last one I had-1 put it in a safe so that we wouldn't lose it. And when I could afford to make my own die and cast for it, I did. Just before the live album I was coming down to my last two or three picks. So now we make about a thousand at a time.

What are they made out of?

It's a very hard plastic—I'm not sure what kind. I want an even harder plastic to be used for the next batch.

Have you tried any stone picks?

No. Actually, I could use anything, and I could change if I wanted to. But I'm used to my picks. However, as I found out when I lost all my guitars and had to replace them, I don't need anything as much as I am simply used to it.

How does your Fernandes copy of a Strat compare to the original?

The Japanese make some fantastic copies. I don't know how they do it, but I'm glad they do [laughs]. The fact is that there are younger people involved in trying to recreate originals. They know what's good about the original Gibsons and Fenders. I'm not trying to put Gibson and Fender down because they've both been very nice to me, but over the years they seem to have introduced production shortcuts, and it has affected certain things—especially in Fenders. The Japanese are going right back to square one and doing all the things that made those originals feel so good. They still don't have the sound, because they're way behind in pickup technology; you've got to use other pickups. But the woods they use and the way their fingerboards and necks are cut—they can make a complete '54 or '59 or whatever you want, and it's exact! And they're so open to criticism that it's amazing. They'll listen to every "er" and "um" you have to tell them.

Do you think perhaps that the American manufacturers don't respond correctly to the needs of guitarists?

I think it's the same as with any profession, any business: Once you're established, you tend to lose the challenge of trying to prove yourself. It's a natural thing. It happened to me in my career, too. The fun in trying to prove yourself is gone because you've proved yourself. I think the Japanese are still proving themselves.

What would you suggest the American manufacturers do?

I want to be helpful, rather than sound as if I'm putting them down, but I think they need to spend more time with musicians, and to put some new blood back into it. Here in the States, there tend to be some pretty old people working on the bodies and cutting the templates; it's only when the guitar gets to the end of the line that there are young guitarists who test them out. In Japan, they've got young people working all the way down the line, so the entire operation is a much younger, hipper thing.

What kind of effects are you using now?

I use either a Boss OD-I Overdrive or an Ibanez Tube Screamer—either of those does the job, although I don't really use them very much. And I also use a couple of echo units: an Ibanez Analog Delay for relatively short delays, and a Korg Stage Echo for longer delays. They operate on totally different principles; the Korg uses a tape, and the Ibanez uses an electronic circuit.

Does this make a big difference?

Oh, yeah. They behave differently, even when you set them at the same interval of echo. The analog is slightly darker in sound because the tape gives you a full frequency range. And that's not necessarily better in some cases, because sometimes you don't want the echo to be as full-range as the original note. So they both have their plusses. I also have a Boss CE-1 Chorus modified by Paul Rivera so that it's cleaner—less distortion. He added independently controlled input and output stages, so I can vary both till there's a nice clean sound to it. I also use one of the new Eventide 949 Harmonizers.

What's your most profound effect?

It's basically an old Foxx fuzztone which Elliott Randall gave me. It's fantastic! It gives that sort of Hendrixy "Stone Free" or "Purple Haze" sound. I combined that with an MXR Analog Delay and an MXR Stereo Chorus—all in one box. So, when I press one button, all of them come on at the same time, and the sound is really quite unique. I used it on "Dig What I Say."

Do you have a name for this combined effect?

I would never have called it this, but the roadies came up with a name for the sound I got on that track: Framptortion [laughs].

It sounds a lot like a guitar synthesizer.

Well, it's not. I use a guitar synthesizer on "Breaking All The Rules," and the solo on "You Kill Me." But on "You Kill Me" it's blended so that it doesn't really sound like a guitar synthesizer. Also on the ballad, "Going To L.A.," for the string parts I used a guitar synthesizer.

There are so many bends in the "Dig What I Say" solo that some guitar synthesizers would have a difficult time tracking the notes properly.

Exactly! It's actually the Frankenstein with the Framptortion.

Whatever became of your talk box?

Oh, it slipped my mind-I don't regard that as an effect, because it's always on my mike stand [laughs]. It's one of those invisible effects because it's always there.

What kind of talk box do you use?

It's basically an original Heil one, but I'm using a different driver now. The people from Dean Markley got it for us. They made a couple of talk boxes for us, but they were lost on the South American tour. So then they told us what kind of driver to get, and we rebuilt a Heil.

Do you mount your effects in a rack?

Yes. In the South American crash we lost my original control unit that took about five years to get into a roadworthy state; so you can imagine that I was a little perturbed, to say the least, that we were going to have to start all over again. I learned that a lot of the stuff that my control unit had before wasn't necessary. The new one uses analog switch integrated circuits instead of relays. I call the whole thing my brain. I plug into the brain, and the effects in the rack are all connected to it. So, if I don't want any effects on at all, they are electronically switched out of the signal path, and the signal goes straight through, bypassing the added resistance of the effects. Only when you have an effect are you going through that extra amount of electronics.

For example, if I have the distortion and chorus on, then it's only going through those two pieces of gear. When they're switched out, the signal goes straight to the amp. Went actually, it does go through some electronics in the brain, but very little. In effect I get the same sound as if I were plugged straight into the Marshall, unless an effect's on.

Does this routing system really improve your sound enough to warrant its complexity?

Oh, yeah. When you've only got one effect and you plug into it, that's fine. But when you've got, say, six effects, you lose your frequency response. So years ago I wanted this, and people are just now starting to get into it. For each effect I have a volume control that lets me boost or cut 10dB, so I can run flat out for rhythm, and when I do a solo the effect I use is already set to boost the volume. It's really handy, too. I also have a power supply to run the effects so that I don't find out that the chorus or distortion needs new batteries by getting a terrible sound onstage night after night.

Do you use anything onstage for rotating speaker or phasing effects?

I'm still using a Leslie, so I have a couple of different outputs from the brain. The first output runs to the Marshall amp; output 2 runs the monitor for our drummer, David; and output 3 is controlled by a standby switch on my foot panel, and it determines if a signal is sent to the Leslie. I also have a pedal to govern the Leslie's speed.

Has your Leslie been modified for higher power?

No. I used to use beefed-up Leslies onstage, but I've learned in the last couple of months that there's nothing like plugging into a stock 145 Leslie and hearing that raw distortion—or clean sound, depending on how loud you have it. Once you start beefing it up and giving it JBL or Electro-Voice speakers, you lose that original Leslie sound. So now I just place a Leslie offstage, mike it, and put it through the monitors.

Do you use a volume pedal?

No, I don't use one basically because I've got all these individual volume controls on the effects. So I play with my guitar's volume, and depending on which effect I've got on, I know how much boost I'm going to get.

Do you have any system to tell you which effects are engaged?

Yes. I have LED indicators for each effect; my pedalboard has two staggered rows of buttons. So all together, there are six effects and three selections of outputs. Also, I can turn the Marshall's standby on or off, so I can just play through the Leslie.

Are there any more electronic wonders in your setup?

I'm sure there will be [laughs], but at the moment, no. It's only a half dozen effects plus the Leslie—and I love to put echo on for pure effect. I know a lot of people who use many more, but I like the guitar just straight, too. I'm not using effects for every solo. I like to plan the act out, because when we started rehearsing, I was doing every solo with every effect, and you couldn't really hear the notes. So I think I'm getting a little bit more selective. You've only got to listen to a Jeff Beck album to realize that he doesn't use that many effects. And gosh, I wish I could sound like that!

Do you have your own guitar synthesizer, or is it so much of a novelty that you only rent one for recording?

I rented one for the album, but then, of course, our dear Roland people knew that if I was going to use it on the album, I was definitely going to need one permanently. So I now have my own.

What model is it?

It's the top-of-the-line polyphonic, a GR-500 system, but I don't use the top-of-the-line guitar. I use the next one down from it, just because I like the color of the wood much better. I only use it on one number at the moment, "Breaking All The Rules," because too much of a good thing... Apart from that, I'd blast the guys out—it's very loud. It's a wonderful device, though. I've been playing around with it in my studio at home. I'm very much into Jeff Beck and Jan Hammer's live album together [Jeff Beck With The Jan Hammer Group Live]. And I can make this guitar synthesizer sound like Jan Hammer—I've learned a couple of his licks—and it's really very interesting. It's the first synthesizer guitar I've played that tracks so well you feel like you're playing a keyboard. Initially, I thought it was very limited in terms of sound. But now, having played with it for a couple of months, I realize that you can invert the envelopes or use the duet button—you can even make French horns! You can get just about everything that you can get from a keyboard synthesizer. Obviously, it's not like a Prophet [keyboard synthesizer], but for a guitar, it's terrific.

Do you find yourself altering your picking technique to facilitate better synthesizer tracking?

No. I don't want to put down other makes, but I had tried the ARP Avatar, and found it incredibly difficult—I had to adjust my playing for it to track. And even though the effects were good, I have to bow down to Roland and say, "This one is definitely it." I know that they had some input from people like Jeff Baxter and Elliott Randall, so they got some really good guitarists to tell them what they expected from guitar synthesizers.

How did you record the synthesizer on "Breaking All The Rules"?

I used two separate amplifiers for the guitar sound—the direct guitar sound from the synthesizer, not the synthesized sound. Then I took the synthesizer directly into the board and processed it in the control room; we put that on one channel. So, we were recording three tracks in all: the synthesizer was on one and the guitar sound was on two separate ones. It sounds like the guitar's coming out of the middle and the synthesizer's on one side. When I sustain a chord, you hear the guitar die out, and the synthesizer carries on like an organ or a string synthesizer.

What kind of amps did you use for recording?

I used one Marshall, and either an old Fender Bassman or a Vox AC-30, so that I got a slightly different sound—it wasn't like equal stereo. I was going for a bigger sound, so I got more highs out of a smaller amp, and I used the Marshall for the thump. You grab every possible frequency that way.

On your last few albums, your guitar had a sweeter, more compressed sound, whereas on the new album there's more of a bite. Is this intentional?

Yes, it is. The amp that I always used for solos on records was an old Ampeg Echo Twin, which was basically designed for accordions. It's not terrifically loud, but it's like having a built-in compressor in there—it gives that sweet compressed sound. It sounded very good with both the Les Paul and the Stratocaster. I used it a little bit on the new album, but I mixed it with the Marshall.

Do you have a preference for microphones for recording?

I like every type of microphone for different things, but I've come back to using dynamic mikes close up on guitar amps, and if possible, tube condenser mikes for further away, to get that room sound.

Why did you use a studio for recording the latest album if you wanted a live sound so much?

I work very well in a live environment. I've been listening to Led Zeppelin—if they don't sound live to you on their records, then you're crazy! I love that sound; I always have. And I've learned from experience that the best way to waste money in the studio is by spending too long: Maybe not having finished writing a song and writing it in the studio. That's the way we were supposed to work at first; we felt we had to. For the new album, we recorded as if it were going directly to a mono piece of tape. So the singer had to sing at the same time, and the drummer had to play at the same time as the bass player—we all had to play live.

So, you feel more at home in a concert situation?

I'm much more uninhibited and more supercharged onstage. We did our first gig after rehearsing, and some of the people in the band hadn't played with me in front of an audience. David Kemper, our drummer, said, "Hey, Pete, you've been holding out on us at rehearsals. You sure change onstage." I'm different onstage than in the rehearsal hall. I'm like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; after midnight I turn to rags like a male Cinderella.

What is it about recording live that makes you prefer it to recording piecemeal in the studio?

There's a certain amount of apparent level, which I think is more emotional than technical, that comes across on an album when everyone is playing live, and the singing is happening. You rehearse the song before you go in, and you imagine you're onstage. There's a sort of magic that comes across when you do that, and I can tell when people have done it and when they haven't. Don't get me wrong, though. I love to hear other people when they've done what I call real studio with a lot of overdubbing. For example, one of my favorite albums is Steve Winwood's Arc of a Diver [Island, 9576]. Now, because he played everything on it, he had to overdub.

Or grow more arms.

Right. So, when you've got a band and you want to record it, there's no point in putting everybody on separately or redoing them, as far as I'm concerned. A lot of people have different views on that. But let's have fun and turn each other on by our playing, and get a great tape like we would from a great show. A tremendous number of people liked my live album, so the approach can't be all wrong. I've now gone back to that. If I could have wished for any album to have followed the live album, Breaking All The Rules would be it. As far as the energy and the feel on it are concerned. I regard this as the follow-up to the live album.

So do you just write off I'm In You and Where I Should Be?

In a way, yes. I mean, there are songs I like on those two albums, but I've really sort of found the direction that I lost in that crazy period. It was enough to distort anyone's thinking at the time. You can say, "Well, you've had success before, Pete!" You know, I had it with Humble Pie, and earlier with the Herd, but it was nothing compared to what Frampton Comes Alive did. And no one can understand that except me—because I was in my shoes.

Was the sudden rush of success frightening?

Not so much frightening as confusing. I don't want to go into it too deeply, but it was just one of those situations where a lot of people pull you all different ways, and everyone gives you these great compliments and offers, and it's very, very, very difficult to say no. And I did a lot of things that I really didn't want to do, when I thought about it later. Now I've gotten right back to the point where I'm totally in control of what I like to play and do, who I want to speak to, where I want to play, and if I want to do a TV show or not do a TV show. And it's very important to me: I'm still sane after all those live albums [laughs]. It was rough there for a while, but it's really exciting now. I'm very "up," I've had a lot of time to think, and I just want to get out on the road and show everybody what we've got up our sleeves.

You have been out of the public eye for a long time.

The sort of image that was pushed upon me was not of a musician—which I consider myself to be. So, if anything, I've stayed a little low just to remind myself and get back to playing music, which is the one thing that I do now, and I'll be doing all of my life. That's the thing that got the live album to where it got—not hype. It was music! And I think that now's the time that I got my own life in the right perspective again.

How were you able to secure such a large hall in which to record Breaking All The Rules?

It was very easy, actually, because A&M Records has this huge soundstage that was once used by Charlie Chaplin. They use it for videotaping and rehearsing, and it just seemed like an ideal place to record. We spent a year preparing the album with David Kershenbaum, who co-produced it with me. We got to know each other, what worked best, and which songs I'd written would be best to record. He suggested that we try recording there, so we brought the engineer, Harvey Goldberg, out from New York, and used a mobile recording truck called Le Mobile, which is from Canada. They parked outside, and we recorded as if it were a live show.

Did you use a 24-track recorder?

We used two 24-track machines, but one at a time. We used a 24-track Studer recorder and a Neve console, and the truck had more studio effects than I'd ever seen in a mobile unit. It was terrific.

How long did you spend recording the basic tracks?

We did 13 or 14 takes in a week-and-a-half. It was really quick. It took a long time to prepare, but once we started recording it, it was really fast. Then we spent another week overdubbing on the soundstage. After that, we brought the tapes back to Media Sound Studios in New York, and finished overdubbing vocals—there weren't that many to do, actually, because we did most of them live. But there were some places where I wanted to try again. We spent about two weeks mixing the songs we wanted. It was so fresh that we were still dancing around to the tracks while we were mixing.

How does this compressed time schedule compare with your earlier recording schedules?

I would say much quicker. Before the live album, it took about six weeks. The last two before Breaking All The Rules took much longer because there was a lot more pressure involved in making them. It was unfortunate, but there's nothing you can do but accept it. The thing I learned from taking a long time to record an album is this: The more time you spend listening to a song before you've finished it, the more time you have to become bored with it. Then you start adding things and overdubbing it and making it sound unreal.

How important is a producer in all this?

Well, David Kershenbaum is the first producer I've worked with since Glyn Johns, who produced Humble Pie. David was very important to this album because I reached a point where I needed another pair of ears to say, "Yeah, that's good" or "No, no, no! Try this." We work incredibly well together. He knows when you can do better, or whether you've had enough for one day. He won't push it because he knows that you've got to be in the right mood to create.

Does he occasionally make suggestions that inadvertently offend your sensibilities as a guitarist?

There are times when he doesn't know what I'm going for, and it takes a little longer to communicate it. But that's rare. I wouldn't work with anyone if I didn't respect their opinion, and quite honestly, David was right most of the time.

Are there any solos that you wish you had redone?

We tried. There were a couple of solos that I tried redoing, and do you think I could get it as good as the one on the basic track? No. The feel was what it needed. Try to overdub in a cold room when there's no drummer, no bass player. I don't work well in those situations. It's like being in a fish tank being watched. I think that I overdubbed the solos on "Dig What I Say" because I was playing rhythm on that, but we overdubbed them the same day. By doing it all in one day, it felt alright. However, when you overdub, you lose the ambience that's being picked up from the other instruments. I don't mind [microphone] leakage at all. Leakage is my friend [laughs]! There are a couple of flubs here and there, but I never want it to be absolutely perfect—there's nowhere left to go then.

Did Steve Lukather do any solos, or was he simply the background guitarist?

Well, I'd say he was the second guitar. He did some riffs with me, like on "Breaking All The Rules." He's a fantastic guitarist. He did some little lead lines that are not solos per se, but they were very tasty.

How long did you rehearse with the entire band before recording?

Two or three days.

That's all? Did you send tapes of the songs to them beforehand?

No. It was just unbelievably quick. To show how quick it was, on "Friday On My Mind" we used the first run-through on the album. We didn't even know the tape was running. It was a hot item—we were the stars of the A&M studio lot.

There seems to be a slap echo effect on the guitars in that song.

I used my Ibanez analog delay for that live. When we mixed, we used a couple of effects such as Harmonizer, but most were added live.

Did you have to alter your usual amp settings to obtain a satisfactory sound in the studio?

Not much. The room wasn't incredibly ambient, but it was a lot better than a regular studio. It was actually like a small theater. There was no hard slap-back, so if anything I added a little bit more top on my sound.

Did you send a direct signal to the board, in addition to miking your amps?

Yes. On "Dig What I Say" the effect is direct. On "Going To LA," the ballad, it sounds like an acoustic guitar, but it's really a '65 Telecaster with the EMG pickups. And there's also a Coral Electric Sitar. There's a story behind that guitar. When I was doing the I'm In You album, the owner of Electric Lady Studios at the time pulled out a guitar case and said, "I know Jimi would love you to have this if he was here to give it to you," and gave me Jimi Hendrix' Coral Electric Sitar. It's just priceless, and I never take it out on the road.

Do you have any other rare guitars besides your Coral Electric Sitar?

Yes. I have a Selmer acoustic tenor guitar that was owned by Django Reinhardt. I got it from a friend of his.

Have you ever recorded with it?

Oh, yeah. I used it on "Rocky's Hot Club" [I'm In You]. I tuned it like the top four strings of a standard guitar. It never leaves the house; in fact, I wish I had it in a glass case.

Do you have any other rare acoustics?

I have one other one, which I believe is an 1840 Martin. It was given to me by Johnny Halliday, the French singer; he picked it up in Nashville a few years ago. It's just a gut-string guitar, and it's really made for looking at. There's no fretboard at all; between all the frets there's just abalone. I never play it, even though it's in good working order. I touch it very lightly.

What modern acoustics do you have?

I have a reissue of Martin's pre-War D-45. It's being mended at the moment because the front cracked. It has a beautiful sound. I also have a Yamaha steel-string that sounds unbelievably like the D-45. I used it on "Lost A Part Of You" on the new album. In fact, both Steve and myself played acoustic on that. I just got an Ovation Adamas 12-string, too. I also have a Goya nylon-string—nothing special.

Do you fingerpick at all?

A little bit. I was taught classical style, but I must admit that as soon as I get a pick in my hand.... I fingerpick sometimes by using the pick and my other fingers, but I wouldn't put myself in a fingerpicking class at all.

Can you read music notation?

Yes, but I don't write out any intricate charts. I write the chords out, and then Arthur Stead, who taught at the Berklee College Of Music in Boston, helps me polish all the chord charts for everybody.

Have you played any slide since "Won't You Be My Friend"[I'm In You]?

Not really. Mark Goldenberg's been playing slide on some of the numbers we've been rehearsing, and I really must get back into it. My desire to play slide goes in phases.

Do you use a steel slide?

Yes. I place it on my third [ring] finger.

Do you have any one guitar designated for just slide?

I've got one—a Zemaitis electric shaped like a Les Paul, with an engraved metal front. Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood have them, too. Its action isn't particularly high—just a little higher than normal, so I can play chords. It's usually tuned to an open chord, though.

What kind of tuning do you use?

I use an open A or an open G. It's sort of like Lowell George's tuning. Now, if I use the open A, the top and bottom strings remain the same—E—and the B string is tuned up to O. The G string goes up to A, and the D string goes up to E. The A string remains the same. When I tune to G, as I did when I wrote "Show Me The Way," I duplicate the A tuning a whole-step lower.

What is it about open tunings that appeals to you?

Well, you sort of manufacture your own chords. You play around until you hit on something. There are some really terrific simple chord forms that sound marvelous. You can almost play piano chords in an open tuning.

Do you ever apply your open tunings to a 12-string?

Yes. In fact, the Adamas 12-string used on "Show Me The Way" was tuned to open G. It sounds terrific.

Do you have any flashy techniques that you would consider unusual, such as Eddie Van Halen's right-hand string tapping?

I figured that one out [laughs]. No, I don't. I'm not a real Van Halen fan, but I'm a terrific Edward Van Halen fan. I think he has tremendous technique. I was reading something that Lee Ritenour said: Eddie sort of took Jeff Beck into his own space. He obviously did a lot of listening to him when he was starting out. I'm a little bit older than him, so when I was learning, no one had that technique yet on electric guitar. But now, people starting out have a lot of different techniques they can listen to, and they can take it their own way very early.

Do you have any favorite guitarists right now?

Well, I've sort of gone ape for Jeff Beck at the moment. I've got about every album he's made. And he's just terrific. I still listen to a little bit of Django Reinhardt. In fact, a friend of mine gave me some written-out Django solos. He did so many versions of the same songs that you have to get the right date and the right month of the version, and then you can actually pick up the record. Luckily, I think I've got them all, and I've learned quite a few parts of his solos. It's enough just to work out a little phrase.

Are there any particular musical styles that appeal to you the most?

No. I still listen to some jazz occasionally, but basically I like everything. I also like listening to a bit of classical now and again, as well as some funky stuff. Today I was listening to Prince, and tomorrow I may listen to Little Feat or Van Halen, or whatever.

Since you like jazz guitar, do you ever listen to, say, Wes Montgomery?

Oh, yeah! I have a whole shelf full of his records. And early George Benson, as well as some of his later stuff. I have a couple albums of him with [organist] Jack McDuff.

Have you ever sat down to learn some of Benson's material?

Yes, I have. In fact, there was a period when I was into George Benson for his speed and technique, Kenny Burrell for his ability to play one note and make it sound soulful, and Wes Montgomery as well for his subtle chord solos and things like that.

What contemporary musicians appeal to you?

Obviously, I like Dire Straits because of Mark Knopfler; he has a wonderful technique and, well, he's my sort of guitarist because he plays with melody. Even though he might be playing the raunchiest chord sequence—you know, a blues thing or something like that—and he's got this wonderful melodic mind for solos. I also like the Pretenders. I went to see them live, and I liked them in concert better than I liked them on album. I just think that there's a chemistry combining Chrissie Hynde's songs and voice and the band. They were terrific. You know, once you've seen someone who's better live than on record, you go back and listen to their record again. The other group I was listening to the other day was one of the first bands I used to listen to: the Shadows. Basically, they were the first band in England to ever have Fender guitars, and nobody could get that sound except them. And I like the Beatles and the Stones.

What's your basic procedure for composing a song?

I write the music first—the melody—and I tape it. If I don't go on to something else, I'll write the words. If I'm in the mood, I'll write the words right away, but sometimes I go on and try to write another melody and chord sequence. Naturally, the words sometimes come at the same time as the music, as with "I'm In You." I sort of wrote a line of melody and a line of words, but that doesn't happen very often. That also happened with another song called "I Wanna Go To The Sun" [Frampton Comes Alive].

Do you usually write your songs using a guitar or a piano?

Lately, it's been guitar more. I used keyboards for writing two songs on the new album: On the ballad "Going To LA" I used a synthesizer, and for "Wasting The Night Away" I used a Wurlitzer electric piano. All the others are written on guitar.

Do you ever work out solos on keyboard to obtain a different perspective, and later transfer them to guitar?

Not intentionally. I'm not really a soloist on the piano; I just play chords and little riffs. The reason I like to write on a keyboard is that there are piano chords and there are guitar chords, and it's interesting to play a guitar solo over something you've written on the piano. It opens the song right up. It's like the difference between writing something in an open tuning on a guitar and playing the solo in standard tuning.

Do you think that if you were to cut loose and play speed maniac you'd be able to solo as melodically as you do now?

I've had my moments when I freaked out, speed-wise. I'm a little faster now than I've ever been. I've done a hell of a lot of practicing, and I'm much more into playing guitar than I ever was. But let me put it this way: There are very few people who can play fast and put feeling into it. A lot of it, I find, comes down to cold technique. I'm not saying that because I'm not a speed freak guitarist; I'm saying it because I could if I wanted to be. It just means sitting down and practicing scales all the time. And in effect, that's what comes out of many people: scales. But when it comes to someone like Django—he could play one note through an entire 12-bar phrase, but it was the way he played it. Then he would go from one end of the fingerboard right up to the top in two seconds flat! But there was something about the way he played that allowed him to retain that feeling. It was probably the whiskey [laughs].

So, there is speed with substance.

Sure. I won't name names, but there are quite a few guitarists who are highly rated, although I don't enjoy them. It's a definite imposition to have to sit down and listen to it because it's so boring. I can see a lot of people saying I feel this way because of jealousy. But I've never been jealous of someone simply because they can play incredibly fast. I was listening to Kenny Burrell at the same time as I was listening to George Benson—I was really doing a jazz guitar study. They're two good examples of how differently two people can play: George Benson is all technique, but he still has feel, and Kenny Burrell doesn't have quite as much technique but he has a lot of feel. I'd like to be able to play as fast as George Benson, but I much prefer to play at my own pace.

As your technique has evolved over the past several years, can you recall any distinct milestones in your growth?

Yes. I've run into what I call brick walls—where you can't seem to go any further, and one little thing that you pick up helps you over the brick wall. One significant technique that I've picked up is the use of harmonics, 12 frets above the note you finger. You can play entire melodies that way. I try to slip those in on occasion. I also like to employ open strings in chromatic runs.

Can you cite any songs on which you've used this technique?

I've mainly used it in my live playing, but here's how it works. You choose a position very carefully, so that you can include the notes in your run. For example, to produce a descending run, I'll make a G on the high E string using my 1st finger; then I'll play the F* on the B string with my 4th finger, and then use the open E string to get the E note. Then I go to another position and I'm ready to go down further. It can have a nice twinkly sound as you go down.

When do you find this technique fits?

Wherever I feel like sticking it in—wherever it fits. I also like the technique where you finger a note with the left hand, then fret a note higher on the same string with the right hand, and then bend the note. Everybody seems to be doing it nowadays. I mentioned this technique and the ones that Eddie Van Halen does to Ed Monteleone; he saw Les Paul at the NAMM show in Chicago, and Les was using all those techniques—playing beautiful arpeggios and things, to make sure everybody realized he was doing those things years ago. Nothing's new!

What would you consider to be the essential Peter Frampton solo collection?

On the Frampton's Camel album, there's an interesting solo in a song called "Don't Fade Away"—nice chords to solo over, too. That was always one of my favorite numbers. We did it live a couple of times, but it's more of an album track than a live song. I really like the solos from "I Lost A Part Of You" and "Dig What I Say" off the new album. Way back, there's a number I did in Humble Pie called "Strange Days" [Rock On] that I liked. And in general, I liked my playing on the live Humble Pie album [Rockin' The Fillmore]—"Hallelujah" and all those songs.

Do you think the press has treated you fairly in recent years?

It can be unfair at times. Let's face it: '77 was the year to knock Frampton! That was just the beginning; I was already on top with Frampton Comes Alive in '76, so it wasn't fun to say, "Wow! Pete's finally made it." It was time to knock me. They're going to anyway, but you have to make sure that you don't give them fuel for the things they're going to use when they try to put you down.

Do you think you supplied them with fuel?

I'll be honest about it. I gave them two albums after the live one that weren't so good because I had so many other things to worry about that I didn't have time to sit down and write like I used to on my way up. So, I wasn't paying as much attention to the new stuff after the live album as I was before. The culmination of all this put-down came when the reviews started getting to the point of "Frampton's just doing the live album set now, and it's not going any further. It's not progressing."

Now, if I had gotten onstage and played any other numbers then that weren't on the live album, the audience would have walked out, because that's what they wanted to hear. But we were on a plane late at night going to a show that was supposed to take place the next day. The plane had been to that city earlier, and on it was a newspaper for the next day with a concert review of the show we hadn't even played yet! It was something like Twilight Zone. It wasn't fair [laughs]!

Cheap shot.

To say the least. As far as the reviews for I'm In You and Where I Should Be went, they weren't good. Those records weren't up to my standards, and I think that had I been a reviewer or a critic, I would have put them down, too. But I think the new album deserves a good review. I really feel that it's a step backwards as well as a step forwards: It regains all the old things that I lost, and I'm now taking them to a new level.

Do you think starring in the Sgt Pepper movie was bad for your career?

The Sgt Pepper movie was a wrong move for anybody to make; even if you were a milkman, it would have been the wrong thing to do. There were two reasons I did the movie. First, someone asked me, "Do you want to be in the movies?" At that point, so many people were pulling me every different way that my ears pricked up. Second, I was promised that there was going to be one of the Beatles in the movie—which never came off. It was rumored that Paul McCartney would be the one.

Also, George Martin [the Beatles' producer/arranger] was supposed to do the music. I figured that it couldn't be too bad. Now it's very easy to look back and say, "Why the hell did he do that?" I hope people realize that it's very difficult to be in that situation and do everything right, because not too many people had been in my shoes at that time. I couldn't say, "No, I can't do this for you. I won't do that. I don't want to." I didn't want to seem big-headed and not do anything. And so I did a lot of things that perhaps I shouldn't have done.

What's your message to guitarists who have been wondering where you've been hiding the last couple of years?

I'd just like people to know that I'm back into rock and roll. I've got the time now, people leave me alone, and I've had time to get back to playing my guitar. I'm doing the things I love, and I remember why I love music, why I love playing guitar, and why I don't want to be an actor [laughs]. I'm not asking forgiveness or anything like that. I'm back to music. I'm back into rock and roll and lots of guitar playing.

First published in Guitar Player magazine, November 1981.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Tom Mulhern worked at Guitar Player magazine for over 13 years and has contributed to Guitar World, Guitar, Guitar Shop, Billboard, Musician, and more. He has edited a number of books, including Bass Heroes: Thirty Great Bass Players, Concert Photography: How To Shoot And Sell Music-Business Photographs, and contributed chapters to The Gibson and 100 Years Of Gibson Guitars. Visit his website here.

![[Putting My] Heart On The Line - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/XChqqeNbm2o/maxresdefault.jpg)