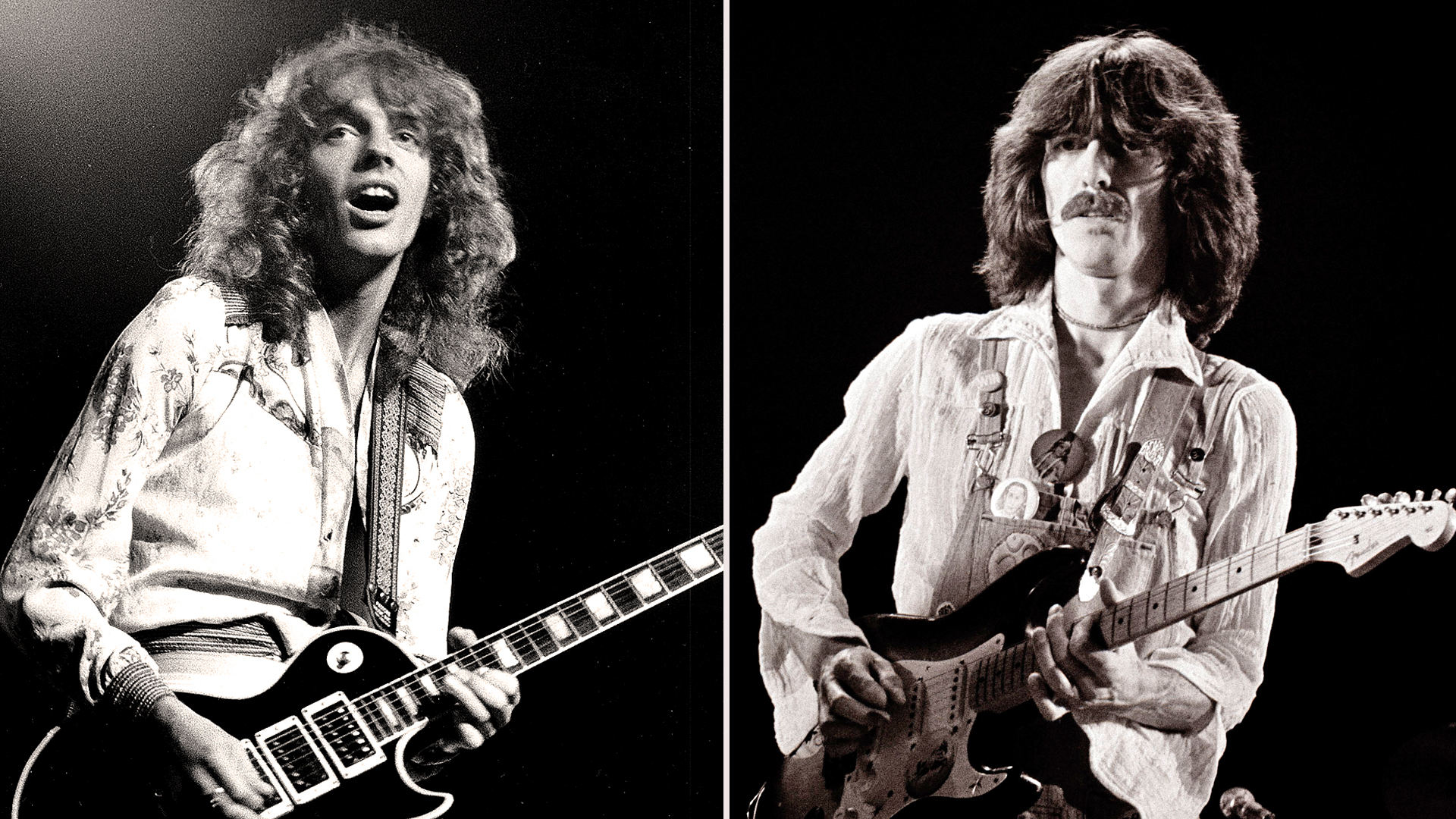

“George said, ‘No, I’m playing rhythm. You’re playing lead.’” Peter Frampton recalled the shocking recording session that led him to perform on George Harrison's 'All Things Must Pass'

The guitarist said it was the first time he met George. It led to a friendship that lasted until Harrison’s death

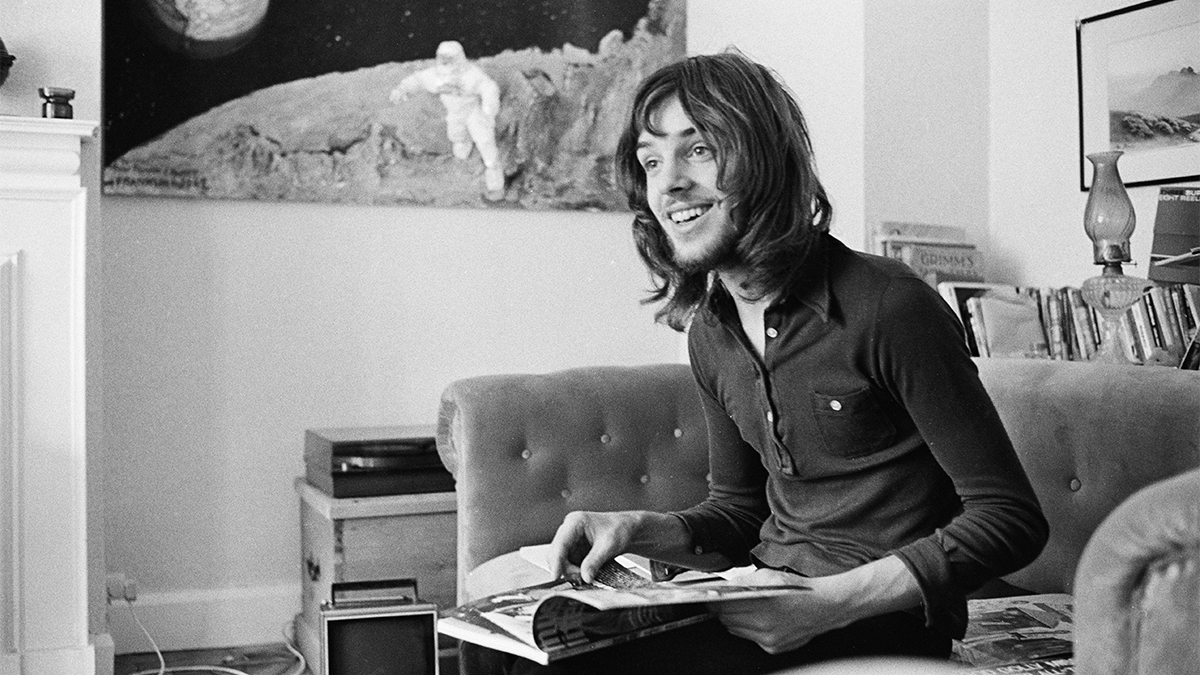

Long before he became known for hits like “Show Me the Way” and “Do You Feel Like We Do,” Peter Frampton was building his career as a guitarist in his native England. After finding success at age 16 in the U.K. rock band the Herd, he joined Steve Marriott in Humble Pie, which quickly established itself in England in the last years of the 1960s.

It was sometime in early spring 1970 that Frampton had a chance meeting with George Harrison that would lead to what he called “one of the highlights of my life.” Thanks to that introduction, Frampton — who previously revealed some of the lessons he learned from Marriott and Harrison — would go on to play acoustic guitar on All Things Must Pass, the former Beatle’s celebrated triple-disc magnum opus.

As Frampton explained to Reverb, their friendship began when he was invited to attend a recording session Harrsion was producing for Doris Troy, his latest signing to the Beatles’ Apple Records. Troy, who would go on to sing backup for Humble Pie as well as Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones and countless acts, was known at the time for “Just One Look,” a 1963 hit she’d co-written under the name Doris Payne, with which the Hollies had a U.K. hit the following year.

As Frampton explained, he was having a drink in a London pub with his friend Terry Doran — who also happened to be Harrison’s assistant — as the session was going down around the corner at Trident Studios.

“Terry said, ‘Do you want to come and meet Harry?’ ” Frampton recalled. “I said, ‘Harry?’ He said, ‘No, no — it's George.’

“They had code names,” he said, laughing.

“I said, ‘Oh my God, uh — yes!' This would be my first Beatle meeting, you know?

Walking into the control room at Trident, Frampton immediately spied Harrison behind the console. “And it's sort of like an apparition, you know, when you see a Beatle. And he goes, ‘Hello Pete!’ And I literally looked behind me to see if Pete Townshend walked in.”

Harrison and Troy were cutting “Ain’t That Cute,” a song they’d co-written and which would be the lead track for her self-titled Apple debut.

“And George says, ‘Do you want to play?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Yes. Okay.’ And he hands me that red Les Paul — the storied Les Paul. And, of course, I had no idea what it was.”

It was, of course, Lucy, the red-finished 1957 Gibson Les Paul that Eric Clapton gifted to Harrison in 1968 and that he subsequently played on the White Album and Let It Be.

“So he shows me the chords and we’re starting to play, and I’m playing very quiet rhythm behind him,” Frampton’s says laughing. “You know, and not wishing to stand out or overstep my bounds.

“And he stopped, and he said, ‘No, I play rhythm, you play lead.’

“So that's when I ended up playing all the licks on this, which ended up being the single,” Frampton says.

Frampton couldn’t have met Harrison at a better time, given that the former Beatle was beginning to record All Things Must Pass, an album that featured an all-star cast of guest artists, including Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, members of Badfinger and many others. Harrison was clearly impressed by Frampton’s performance and manner at the Troy session, and just a few weeks afterward invited him to participate.

“He said, ‘I’m doing a solo album. I'd like you to come and play some acoustic with me,’” Frampton recalled.

It’s not clear which tracks Frampton performed on, and he has stated he can’t remember after so many years. He refers to playing on “about five or six of the more country tracks,” and it’s largely accepted that he played on “Isn’t It a Pity.” Part of Frampton’s confusion is down to producer Phil Spector, who requested numerous instrumental overdubs to achieve his signature wall of sound production. As Frampton told Reverb, Harrison requested his presence for many of these overdubs, which have blurred his memory.

“After we’d finished those sessions, George called me back up and said [imitating Harrison], ‘Guess what? Phil wants more acoustics!’ I said, ‘You're kidding me!’ He said [in Harrison’s voice], ‘No!’

“So we're sitting in front of the control room, there’s Phil Spector in there, and the two of us are just between takes, jamming, you know,” he recalled. “Probably one of the highlights of my life.”

Frampton, who is planning two 10-date tours of the U.S. this year, recently told attendees at Martin Guitar's NAMM 2025 booth about the time he performed Harrison's "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" onstage with Harrison's pal Clapton. He said that, just like Harrison, Clapton insisted he play lead.

"It was one of the most exciting moments of my career," he said. "I've met Eric many times. I've spoken with him, but we've never ever played together. And, of course, I'm a huge fan."

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened