“Jimi Hendrix was a great player, but he wasn't really creative.“ Pete Townshend talks originality, playing loud and which guitarist was first to use feedback

He says Marshall's '60s amps were rife for experimentation while discussing his “musical” use of screaming amps

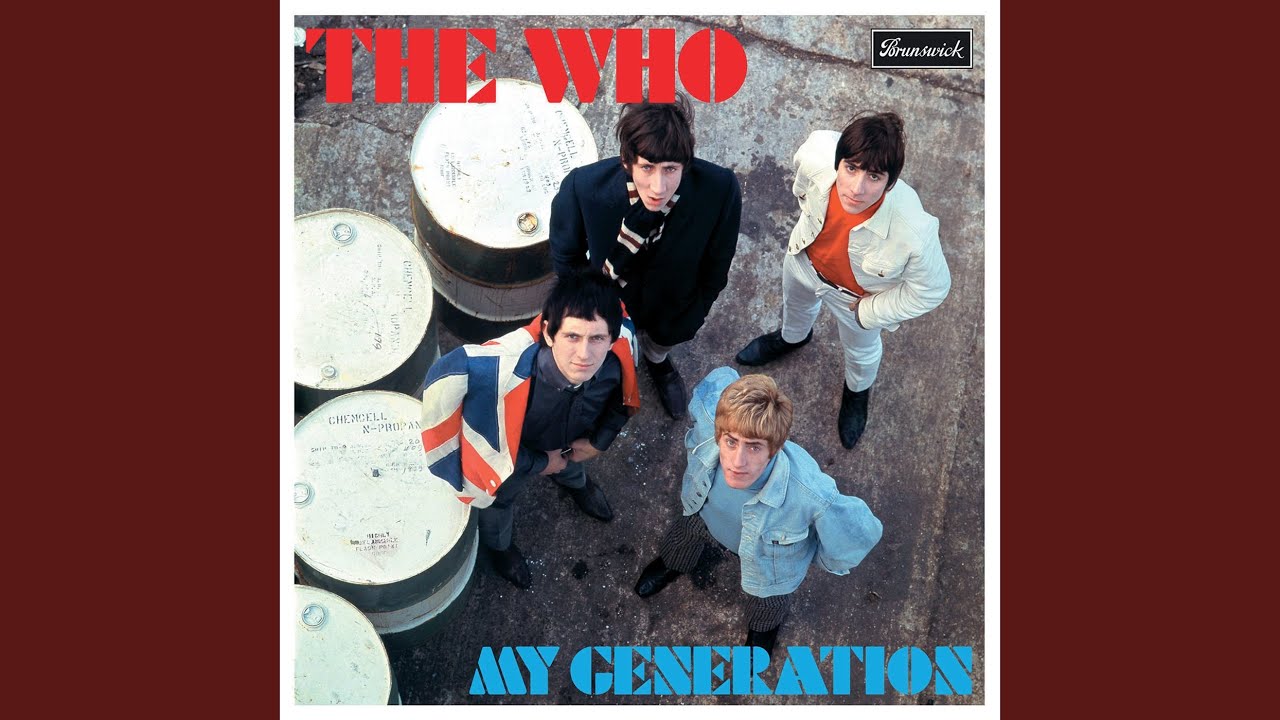

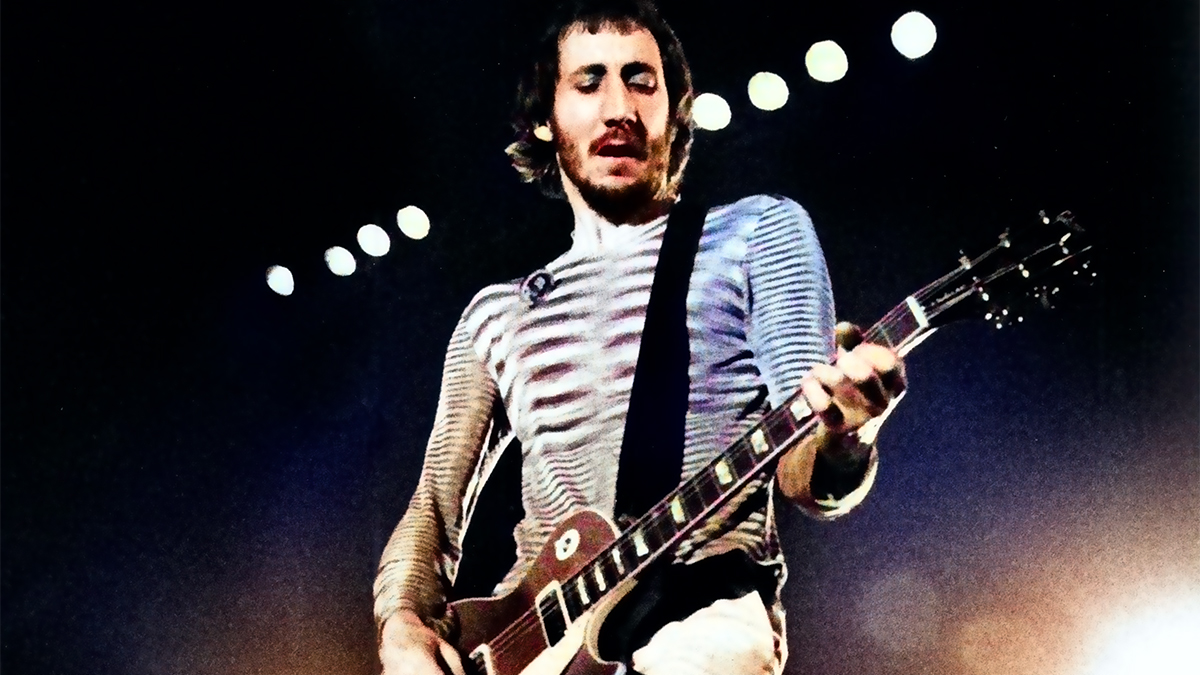

Whether smashing guitars or popularizing the concept album, the Who’s Pete Townshend has always done things differently. In a newly resurfaced 1990 interview with Guitarist magazine, he sheds light on his change-making use of feedback. At the same time, Townshend takes the opportunity to point out that Jimi Hendrix wasn't doing anything with guitar that he and Eric Clapton hadn't already made part of their repertoires.

Townshend credits three factors for influencing his use of amplifier feedback during his early playing days. The most relevant force was the sheer volume of the British group's stage show, which was in part an effort to impress his art school peers.

“I'm afraid I was an arty little sod and I was actually experimenting,” he said when asked if his feedback shenanigans were calculated or a happy accident. “I was at art school, surrounded by real intellectuals, people that were experimenting all the time. I was greatly impressed by all this and wanted to please these people.

“A lot of it was posing, trying to drag something out of the band that it was resisting. As I got louder, [bassist] John Entwistle got louder by inventing the 4x12 speaker cabinet, which he did with somebody up at Marshall. Then I got a 4x12 cabinet and put it on a chair, so then he invented the 8x12 cabinet, to get louder than me, and I invented the stack by getting two 4x12s and stacking them up."

But there was more to it than a volume war. Townshend says it was also a way to drown out the loudmouths in their audience.

“Our experimentations were all to do with our irritation with the audience, who heckled if you played a rhythm-and-blues song that they didn't know," he says. "You'd get blokes in the back with their pints of beer shouting, 'What's all this rubbish? Play some Shane Fenton!' And we just got louder as a result."

The upside to it all is that Townshend and the Who became known as rock's loudest band, a label that served them well as bands moved from clubs to arenas to stadiums in the 1970s and '80s.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It shows that radical experimentation really is worth pursuing," he says. "Because even though it might feel stupid and pretentious if you do discover something new, it's your property and you're identified with it forever.”

Townshend accepts he wasn’t the only player who found feedback worth embracing, although not all players can agree on who got there first. Some point out that John Lennon was perhaps the first to use it intentionally and creatively when he employed it on the opening of his 1964 Beatles song "I Feel Fine." But Townshend says the use of feedback was gaining popularity with bands as early as 1963, when Jeff Beck used it with the Tridents, two years before he joined the Yardbirds.

“Other people stumbled on feedback at the same time as me,” Townshend says. “Jeff Beck was using it when Roger [Daltrey] went to see the Tridents rehearsing.

“He said, 'There's a shit-hot guitar player down the road and he's making sounds like you.' Then later, when we supported the Kinks, Dave Davies was adamant: 'I invented it, it wasn't John Lennon and it wasn't you!' ”

But Townshend pours cold water on Davies’ claim.

“I believe it was something people were discovering all over London. These big amps that Marshall were turning out — you couldn't stop the guitars feeding back!”

Radical experimentation really is worth pursuing. If you do discover something new, it's your property and you're identified with it forever

Pete Townshend

The origin of using feedback as a tactful play is admittedly blurry. But one thing Davies and Townshend can agree on is how their use of it differed. Davies was more animalistic. Townshend’s art school background, meanwhile, saw him longing for a more musical application.

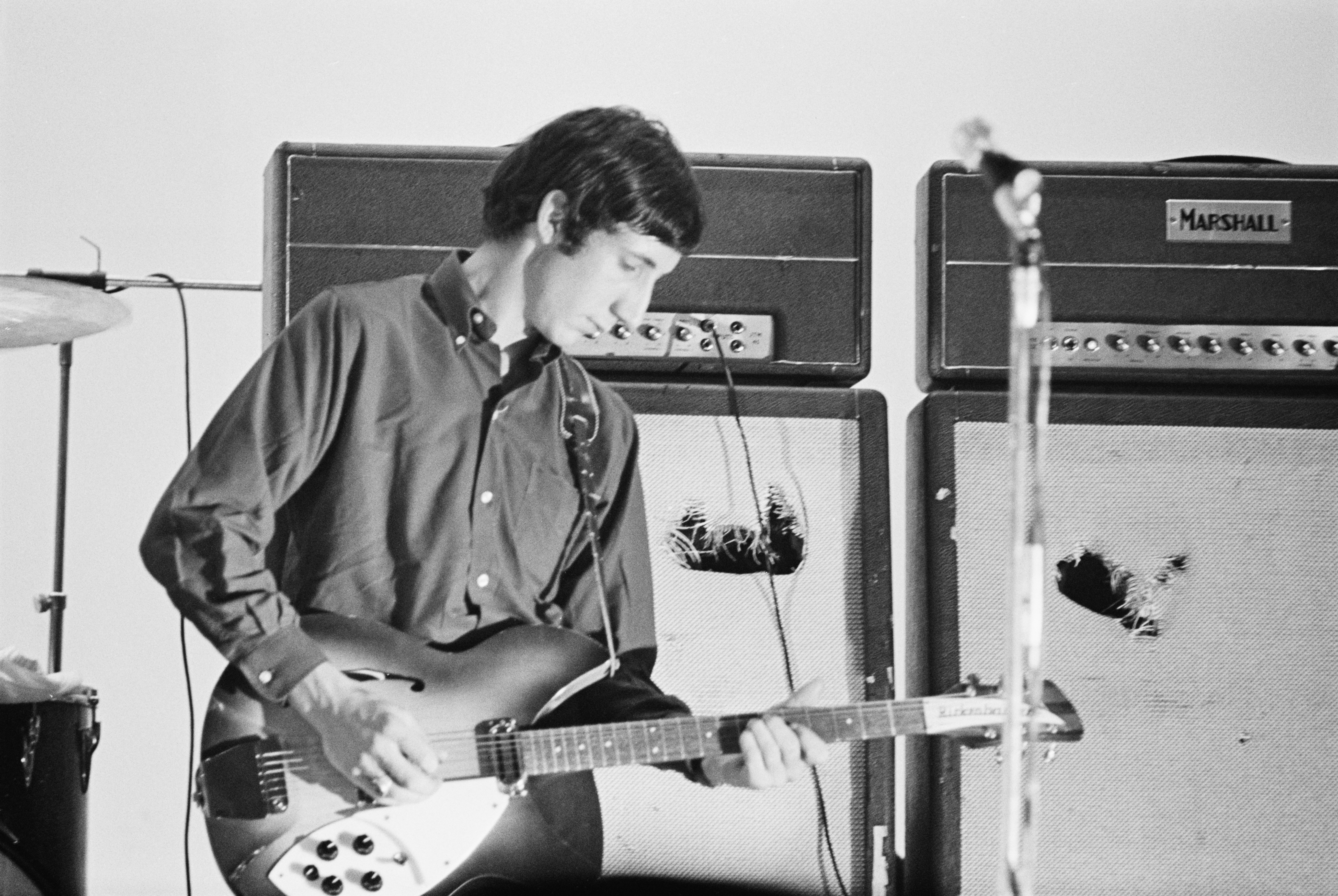

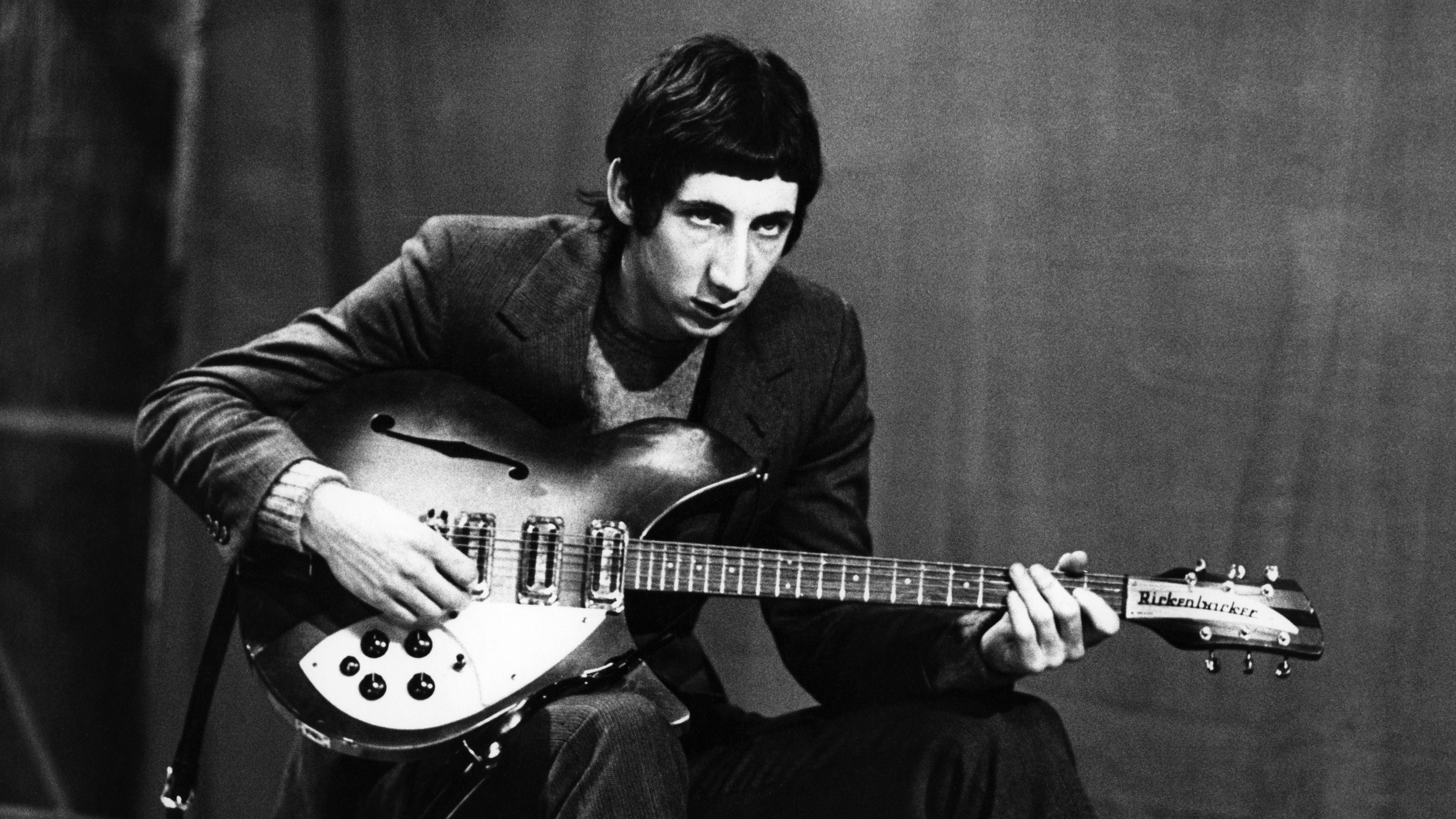

“On 'Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,' during the solo, on the note A I would flick a harmonic, get it feeding back, and then go 'dit-dit-dit-dar-dar' with the switch. And by standing at certain angles I could get incredible sounds out of it, some of which were just characteristics of the Rickenbacker body, which I stuffed with paper.

"You could control it and it could be very musical,” he goes on. “Certainly that sort of thing where you hit an open A chord and then take your fingers off the strings... the A string is still banging away but you're hearing the finger-off harmonics in the feedback.

"Then the vibrating A starts to stimulate harmonics in other strings, and it's just an extraordinary sound, like an enormous plane. It's a wonderful, optimistic sound and that was something that happened because I was posing — I'd put my arms out, let go of the chord then find that the resulting noise was better.”

The interview also saw Townshend discussing Jimi Hendrix’s talents. His fellow feedback-loving guitarist Jeff Beck said Jimi's arrival on the scene nearly ended his career. While Townshend was impressed by his chops, he didn't find him to be an original when it came to his more blues-based guitar playing and some of his stage antics, which included destroying his instruments as Townshend had been doing for years.

“Hendrix was a great player,” he says, “but he wasn't really creative. He was dealing in other people's ideas, old blues things and tricks that were either borrowed from Eric Clapton or the pyrotechnic things that he had caught off watching me.

“He used to follow the band around, watching, and then he suddenly appeared on stage doing all this stuff. But it was something else that made it extraordinary. Talk to the women who came in contact with him — he literally enchanted them. He was a pretty unremarkable kind of gnarled-looking guy, but he was a real enchanter.”

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.