“John learned to play guitar upside down too. That’s more unusual.” Paul McCartney revealed he and John Lennon were both ambidextrous guitar players, thanks to this one thing

McCartney also explained how he came to understand the bass guitar's transformational power while recording the Beatles' "Michelle"

The Beatles’ Anthology doc-series is back on screens this week, and as the first installment reveals, Paul McCartney and John Lennon spent a lot of time playing face to face as they learned to play guitar and write songs.

As a lefty, Paul McCartney had an extra complication. Left-handed guitarists have never had it easy, especially in the early years of the instrument's U.S. popularity. Reportedly, Jimi Hendrix’s father forced him to play right-handed when he was a youngster out of belief that left-handedness was a sign of the devil. Jimi accommodated his dad when he was around and then flipped the guitar for left-handed playing when he was gone.

Paul McCartney had it somewhat easier. A southpaw, his dad didn't force him to play right handed, but like other lefty guitarists he had to tweak his Zenith acoustic guitar by switching the string order and making homemade fixes to the nut. Even so, over time he managed to learn how to play guitar right-handed given that much of the time he was among right-handed guitarists with no suitable instrument in sight.

“I can play right-handed guitar a bit, just enough for at parties,” he confirmed to Guitar Player in 1990. “Hopefully, by that point everyone is drunk when I pick it up, because otherwise they're going to catch me. But I could do that."

He explained that it would have made little sense to ask if he could re-string someone's guitar. "And at a party, you only want to play it for 15 or 30 minutes or so, and by the time you've goofed up their guitar and you hand it back to them, they've got to string it back again, and it's silly. So I had to learn upside down.”

John Lennon found McCartney’s left-handedness useful for when the two were practicing. Lennon, whose early musical skills consisted of playing banjo chords on guitar strung with five strings, picked up much of his chord knowledge from McCartney, who would position himself opposite Lennon, providing him with a mirror image of how to fret a chord. Some of that left-handed knowledge undoubtedly seeped into his brain. As McCartney revealed, Lennon had no difficulty playing McCartney’s left-strung guitar.

“It's funny: John learned upside down too, because of me — because mine was the only other guitar around for him, if he broke a string or he didn't have his,” McCartney said. “That's more unusual; left-handed guys can nearly always play a straight guitar.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

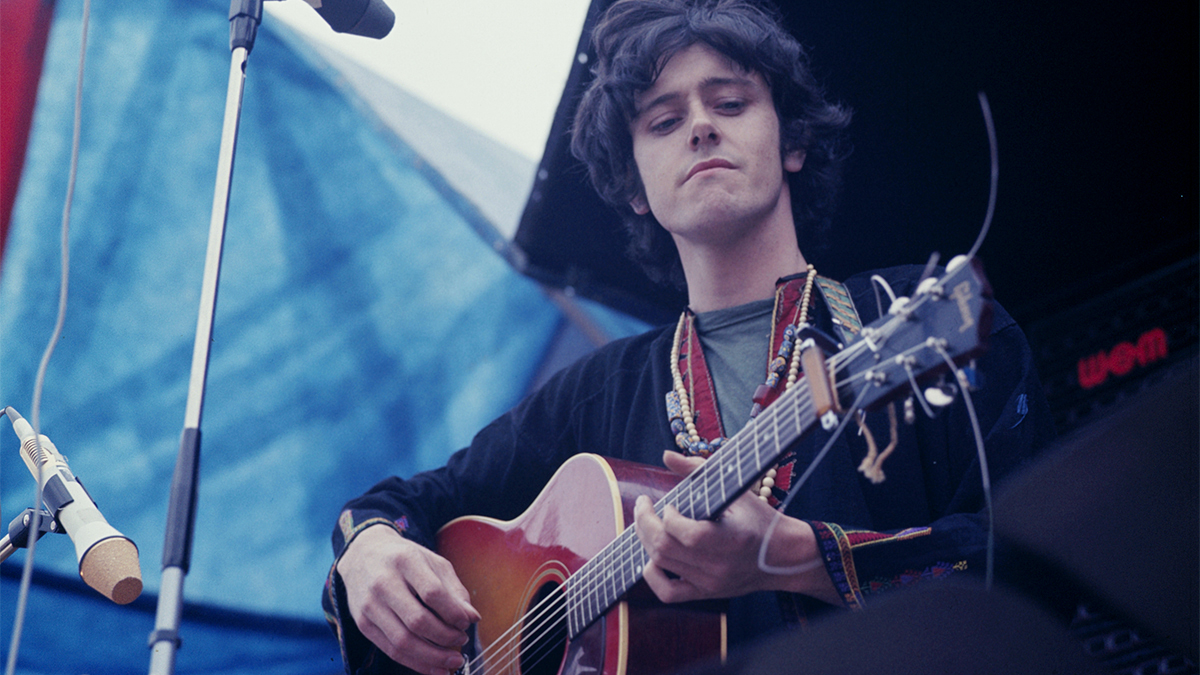

McCartney’s recollection offers an interesting insight into Lennon’s guitar talents. As he told Guitar Player in that same interview, Lennon was also the only Beatle who learned how to properly fingerpick, a skill he learned from folksinger Donovan while they were in India studying with the Maharishi.

McCartney recalled that he was playing a Rosetti Lucky 7 electric guitar by the time the Beatles began performing in Hamburg in 1960. The guitar didn’t last long,

“When I went to Hamburg, I had a thing called the Rosetti Lucky 7, which is a really terrible British guitar with terrible action,” he said. “It just fell apart on me — you know, just the heat in the club and the sweat made it fall apart. Eventually I sort of busted it — early rumblings of the Who! — in a drunken moment. It was busted somewhere, and it had to go. So I ended up with my back to the audience, playing piano, which was then the only thing I could do unless I could get a new guitar.”

It soon wouldn't matter. When bassist Stuart Sutcliffe quit the group in July 1961, it fell to McCartney to take on bass guitar duties. Lennon didn't have the skill for it, and Harrison was too valuable as a lead guitarist. While McCartney at first resented his new position, he came to embrace it.

But he said it wasn’t until 1965, during the making of Rubber Soul’s “Michelle,” that he discovered the instrument’s power to create harmonic tension and release.

“I did pretty much get lumbered into playing bass. I didn't really want to do it, but then I started to see some interesting things in it,” he said. “One of the very earliest was in ‘Michelle.’ There's that descending chord thing that goes, [sings bass notes] ‘do do do do, words I know, do do do do do, my Michelle’ — you know, the little descending minor thing.

“And I found that if I played a C, and then went to a G, and then to C, it really turned that phrase around. It gave it a musicality that the descending chords just hadn't got. It was lovely.”

It’s a transformational power acknowledged by players like Sting, and one that Neal Schon discussed when he spoke with us about creating the Journey hit recording of “Don’t Stop Believin’.”

“And it was one of my first sort of awakenings,” McCartney continued. “’Ooh, ooh, bass can really change a track!’ You know, if you put the bass on the root note, you've got a kind of straight track.

“But later I learned how to make other notes work for me, as Brian Wilson was to prove on the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, a big, influential album for me. If you're in C, and you put it on G — something that's not the root note — it creates a little tension. It's great. It just [takes a long, expectant, gasping breath] holds the track, and so by the time you go to C, it's like, ‘Oh, thank God he went to C!’

“And you can create tension with it. I didn't know that's what I was doing; it just sounded nice. And that started to get me much more interested in bass. It was no longer a matter of just being this low note in the back of it.”

The Beatles Anthology continues streaming with Episodes 4–6 on Thursday, November 27 and Episodes 7–9 on Friday, November 28.

Elizabeth Swann is a devoted follower of prog-folk and has reported on the scene from far-flung places around the globe for Prog, Wired and Popular Mechanics She treasures her collection of rare live Bert Jansch and John Renbourn reel-to-reel recordings and souvenir teaspoons collected from her travels through the Appalachians. When she’s not leaning over her Stella 12-string acoustic, she’s probably bent over her workbench with a soldering iron, modding gear.