"We thought his music was very similar to ours, and we latched on to him amazingly quickly.” Paul McCartney explained how a youthful error led him to write one of his greatest guitar tracks for the Beatles

"Blackbird" developed from his and George Harrison's love of Bach's Bourée in E minor and their attempts to master the piece as young teenagers

"I wrote that in my front parlor in Forthlin Road. I was about 16,” Paul McCartney recalled of his acoustic guitar–driven country-western tune, “I’ll Follow the Sun.” "It was one of those very early ones. I remember standing in the parlor, with my guitar, looking out through the lace curtains of the window and writing that one."

Though composed circa 1958, “I’ll Follow the Sun” wasn’t completed until 1964, when McCartney rewrote its middle eight so the song could be recorded on Beatles for Sale, at a time when he was lacking new material. “I’ll Follow the Sun” was the first of a few noteworthy times McCartney returned to a song from his youth as he sought material or inspiration for new songs. He did it again in 1965 with “Michelle,” a tune written while he was in art college as a farcical imitation of French cabaret, and once more in 1967 with “When I’m Sixty-Four,” a song he again drafted in the style of cabaret music when he was just 14.

Clearly, McCartney had a rather sophisticated sense of music as a teen, one that comprised such far-flung styles as country-western and musical theater.

But it turns out there was a touch of classical in his repertoire back then as well. It just didn’t show up until years later in a solo performance from the Beatles’ 1968 White Album: “Blackbird.”

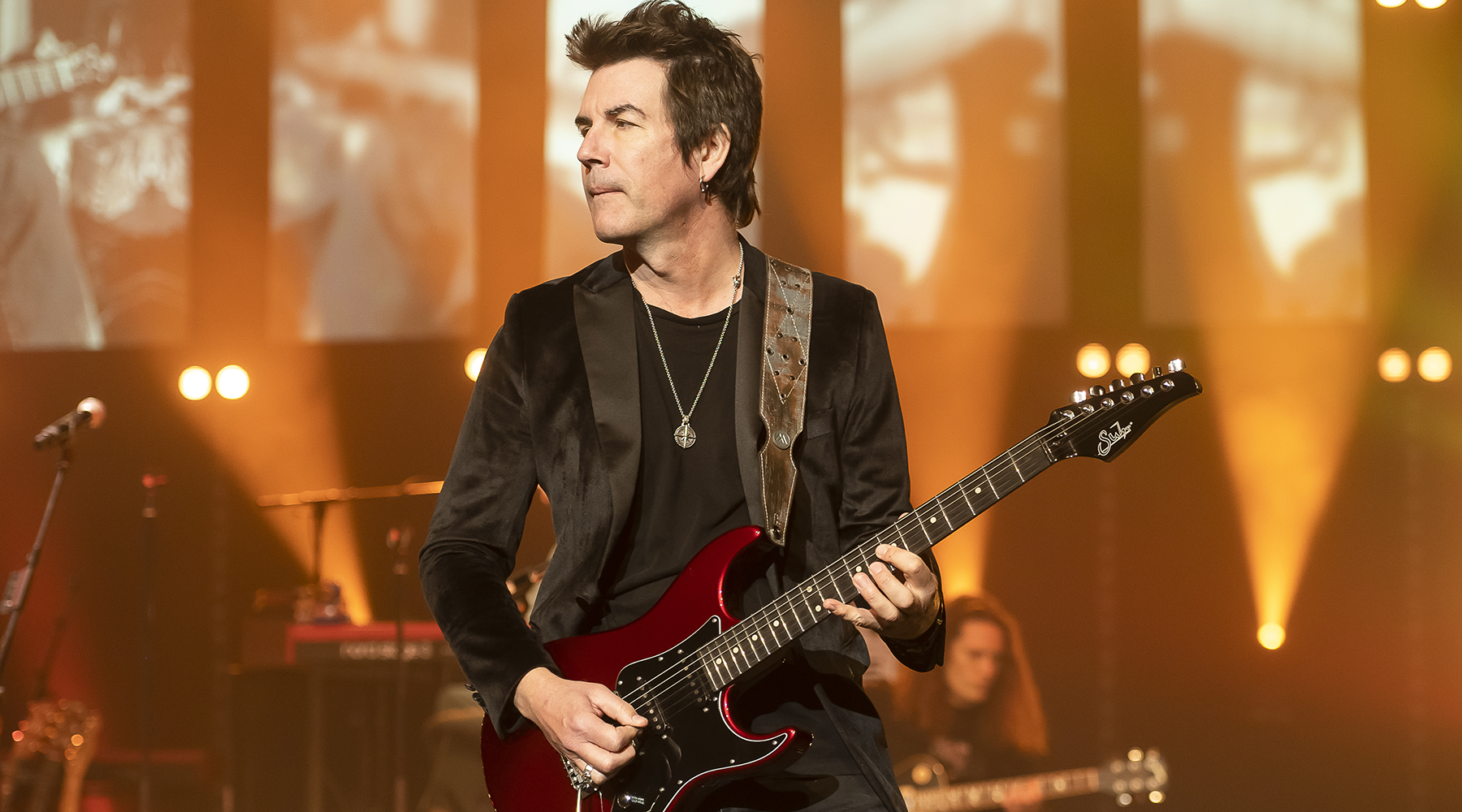

It’s a song that owes as much to Bach as it does to George Harrison. McCartney and Harrison met while they were both about 14, drawn by their common interest in guitar. They practiced together and helped each other improve on the instrument. And one of the songs they both attempted to learn, to no avail, was Bach’s Bourrée in E minor, the fifth movement from his Lute Suite in E minor BWV 996. Both youngsters were attracted to the song’s moving melody and bass lines.

"The original inspiration was from a well-known piece by Bach, which George and I had learned to play at early age, he better than me actually,” McCartney explained in his 1997 memoir, Many Years From Now. As he revealed then, he was drawn to the “harmonic thing between the melody and the bass line, which intrigued me.”

Bach, he explained, was one of their favorite composers. “We felt we had a lot in common with him. For some reason we thought his music was very similar to ours, and we latched on to him amazingly quickly.”

Speaking on the British TV talk show Parkinson in December 2005, McCartney elaborated on how Bach led to "Blackbird."

“How that sort of started, it was because me and George used to sit around learning all the old basic rock and roll chords, but there was one little thing we used to do, which was a sort of semi-classical thing… Well, it was actually classical, but we made it ‘semi,’” he remarked to laughter from the audience.

As he explained, he and Harrison got part of Bach's melody wrong, but McCartney said their youthful invention was the bit he always liked best. And it was this part that he ended up adapting into “Blackbird,” by shifting it from E minor to the relative major, G.

What’s remarkable is that, even if you knew both Bach’s work and McCartney’s song, the connection wouldn’t be evident. But just as remarkable is the fact that McCartney, more than 10 years after attempting the play Bourée in E minor, drew from his childhood experience with the piece to craft a new tune as elegant and original as Bach's own.

McCartney — who has said he sees himself primarily as an acoustic guitarist — began writing “Blackbird” while the Beatles were studying with the Maharishi in India in early 1968, inspired by the call of a blackbird one morning while he was meditating. The song finally came together at his farm in Scotland, its lyrics influenced by events in the struggle for Black civil rights in the United States.

“I was in Scotland playing my guitar and I remembered this whole idea of 'you were only waiting for this moment to arise,'” McCartney explained in a 2002 radio interview with KCRW's Chris Douridas. “You know, the Black people's struggle in the southern states, and I was using the symbolism of a blackbird. It's not really about a blackbird whose wings are broken, you know. It's a bit more symbolic.”

"Blackbird" was first recorded in May of that year as a demo at Kinfauns, George Harrison's home in Esher, where the Beatles were compiling songs for inclusion on the White Album. Footage of McCartney in Abbey Road Studios on June 11 shows him recording the song for the album as his girlfriend Francie Schwartz looks on.

As McCartney has repeatedly shown, his inquisitive mind draws inspiration for his songs from the past and present, and from culture at home and abroad. Most importantly, he never lets a good idea go unused. The proof is in the records.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened

![The Beatles - Blackbird [REHEARSAL] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/KoywIMfEIvU/maxresdefault.jpg)