“The last conversation I had with Tom, he said, ‘If I have to be in a wheelchair, I'm going to do it.’” As he prepares to release his new memoir, Mike Campbell shares the joys and struggles of his years as Tom Petty’s guitar partner

With his upcoming memoir, Heartbreaker, due March 18 from Hachette Book Group, guitarist Mike Campbell delivers a spellbinding account of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, the classic American band he was a part of since its inception till Petty’s tragic death in 2017.

With captivating candor and a compelling narrative flair, Campbell relives his musical and personal journey, from a hardscrabble upbringing in Florida to meeting Petty and joining his fledgling band Mudcrutch to the heights of fame with the hit-making Heartbreakers.

In addition, he chronicles multi-Platinum collaborations with Don Henley and Stevie Nicks, as well as his post-Heartbreakers activity leading his own band, the Dirty Knobs, touring with Fleetwood Mac. It’s achingly poignant, sharply funny and remarkably detailed, a fact made more astonishing as Campbell penned the book without notes.

“In the early days, I tried to keep a journal,” he says. “It went from Mudcrutch to ‘got to L.A.’ But it got so depressing, because every day I'd write, ‘Went in the studio, couldn't get a track, went in the studio, couldn't get a track.’ After 20 pages of that I said, ‘Forget this.’ So there was no journal. It's was all in my head – what's left of it.”

“I think I brought a musicality that Tom wasn’t capable of.”

— Mike Campbell

He pauses, then says, “But I'll tell you, I know it's a good book. That’s not just ego — I know it's good because when I read it for the audio version, there were times when I got choked up.”

Paired with Petty, Campbell wrote enduring songs such as “Refugee,” “Here Comes My Girl,” “You Got Lucky” and “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” among others, and his memorable riffs and solos helped to numbers like “American Girl” and “Breakdown” into beloved classics.

As it is with any great songwriting combination, Petty and Campbell brought to each other matched though disparate strengths.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

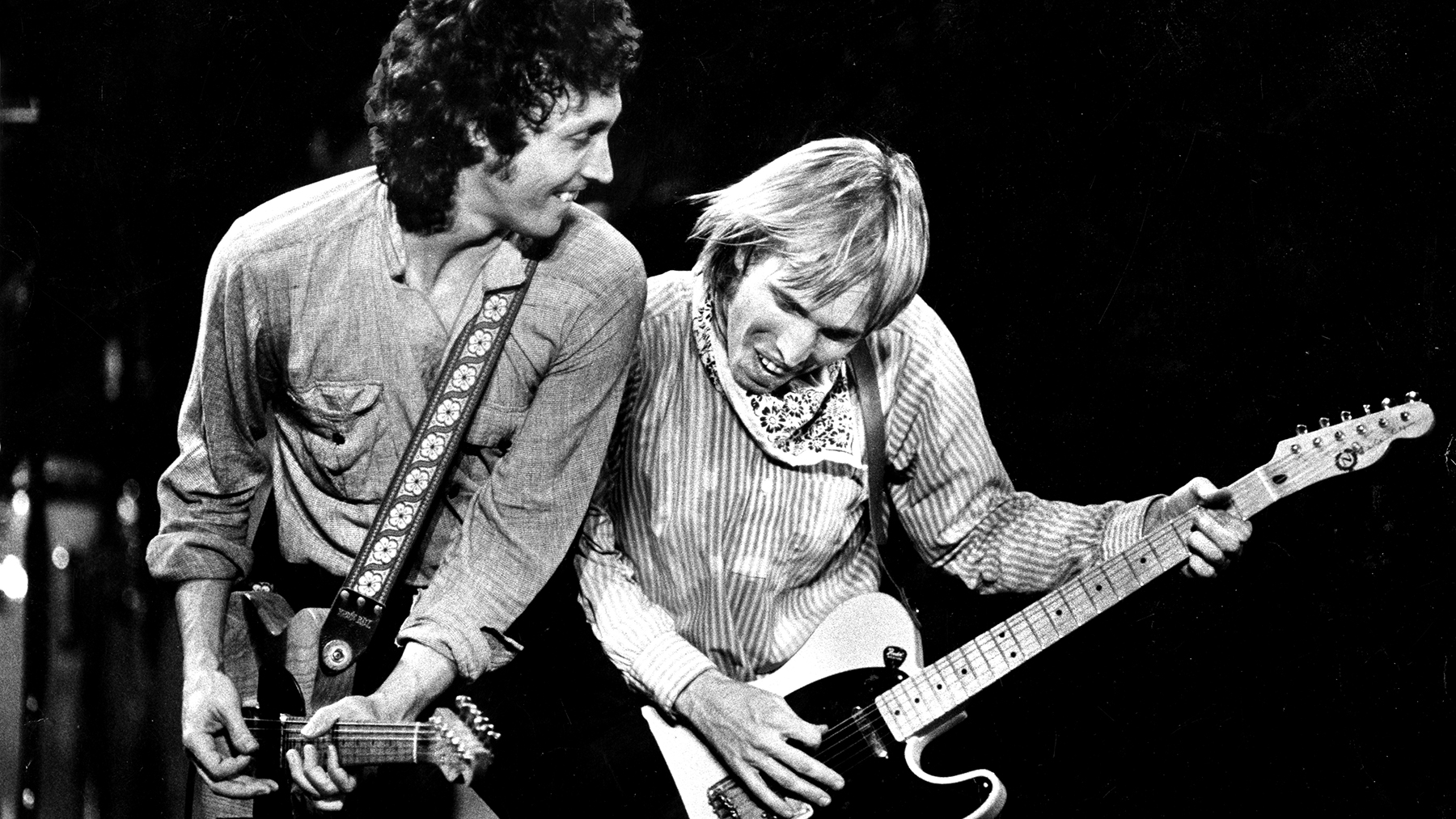

“I think I brought a musicality that Tom wasn’t capable of,” says Campbell, who recently spoke with us about his Fender Broadcaster, the electric guitar at the heart of tracks like “American Girl.”

“I had guitar techniques and musical influences that I could express to him in his songs, or present to him as my music, that he couldn't have done on his own.”

He smiles, then recalls, “In fact, there was one instance when I gave him something that sounded like a Heartbreakers song, and he said, ‘That sounds too much like me. Go do something that I can't do.’”

Campbell pulls no punches in recounting the band’s interpersonal conflicts, and in the case of Petty he doesn’t indulge in hagiography (“Sometimes he made me so angry I couldn’t look at him,” he writes). But what ultimately comes through is the guitarist’s genuine gratitude for the life he’s led and the bonds he formed along the way.

“Lord knows what would've happened if Tom and I never met,” he says. “As I wrote the book, I realized how many miracles have happened to me through timing, luck, divine intervention. I started with nothing, and these songs came to me from somewhere. There were chance encounters with my heroes, and of course, there was my relationship with Tom.

"We had our brotherly friction here and there, but there was a deep love that kept us together through all the rough times.”

You mentioned how Tom once asked you to write something that didn’t sound like him, but when you played him your demo of “The Boys of Summer,” he rejected it as “too jazzy.”

Yeah, and in the version I showed him, when it went to the chorus, instead of going to that glorious major chord, I went to some kind of minor thing. I don't know what I was thinking. It wasn't really jazzy per se, but I knew what he meant. It didn't lift up like a chorus should. I took that advice, and after he left, I thought, “I’ll change that chord. I can make a better chorus there.” The version that Don Henley heard had the new chord. Later, when Tom heard it, he said, “Ohhh. You changed it.”

It’s amazing how your journey with Tom started with his band Mudcrutch. You two jammed and he said, “Join the group, Mike.” It’s like he wasn’t even asking.

Tom was like that. He was undeniably dynamic. He was driven, and he could convince you to go on the road with him. “I'm going down this path. Come with me.” He had that great leadership quality, and I was sitting duck for that kind of thing.

You come across in the book as very non-confrontational, a peacemaker almost. But there was one big moment, during the making of Damn the Torpedoes, when you stood up for yourself and asked for a bigger piece of the pie. Tom just looked at you and said, “But I’m Tom Petty.”

That's a perfect example of our relationship, me going, “Don't you think dah, dah, dah?” And he goes, “Yeah, but I'm Tom Petty.” I couldn't really argue with that. I could say, “Well, yeah, but I'm Mike Campbell,” and he would go, “Nobody knows who that is.” So it was checkmate, and even though it stung a little bit, I had to give him credit. Tom would always give it to you straight, and I couldn't argue with that.

“He goes, ‘Yeah, but I'm Tom Petty.’ I couldn't really argue with that.”

— Mike Campbell

It’s eye-opening to read how the group seemed to be on the verge of breaking up at various points. A lot of people didn't know that.

I think people will see the struggle within the band, how it wasn't all Gold records and sold-out shows. Bands are very delicate animals. There's egos and resentments that can develop. Wives sometimes can split bands up. Everybody's passionately involved in this thing, and it can get very intense. I don't think a lot of people realize how tough it is to keep a band together. Things come up and one guy gets mad and says, “I don't need this shit.”

The reason why the Heartbreakers didn't break up was because Tom and I had a brotherhood. It’s hard to define, but no matter what happened from day one with him, the music came first. Whatever we might have agreed or not agreed, we agreed that the music was more important than anything else. We couldn’t let that fall apart, no matter what.

I was a peacemaker. I mean, guys in bands have different role. Tom was a leader. I was a kind of a peacemaker. Benmont [Tench, keyboardist] was a genius. Stan was a ball of fire, and Ron was the quiet, solid bass player. I embraced my role, and if there was a conflict that might break the band up, I wasn’t going to let that happen. I'm going to get in there and negotiate to keep it going. And we did.

There’s too many songs to touch on, but I was struck by your account of “Don’t Do Me Like That.” Tom had that one kicking around before there was a Heartbreakers, but it didn't make the first two albums.

It almost didn't make the third record if it weren’t for the second engineer, who said, “Do you remember that track you guys cut the first day? Let’s hear that again.” The title was a line Tom got from his dad. It started out there and it became a good song.

Of course, there’s “American Girl.” You write that the song didn’t truly come together until you came up with its riff.

Well, that was what I did on a lot of songs: I’d try to find a part that could be powerful and help the song as much as the vocal. That’s what I always thought – “It’s what George Harrison might do.” These things, I don’t know… it’s just another miracle. I have an ability to hear that, and with Tom, I think that's what endeared him to me. I could take his Bo Diddley four chords and turn them into something that was maybe a little better than he would've done on his own. If you take a lot of those guitar parts out, like on “Breakdown” and stuff, it's not the same song.

“That tonality we found between the guitar harmonics and the energy and the riffs. That was the sound of our band.”

— Mike Campbell

You single out “American Girl” as perhaps the best song you guys ever did.

There's something about it, yeah.

There’s also something tragically poetic about it. You said that it was the sound of the band discovering its identity, and sadly it would be the last song you would play with Tom.

Yeah. Irony.

Given all that, does it now have even more significance to you?

Well, now that you mentioned it, yeah. But I don't ever think of “American Girl” as the last song we ever played together unless somebody brings it up. It's like one of the first songs we ever played together. I don't have a sad attachment to it – it’s too much of an optimistic burst of joy.

But I am glad we played that song together at the Hollywood Bowl, and we played it together for decades. Every time we played it, the hair on the back of my neck would stand up. There's something about it that's just inspired and poetic and exuberant. It's the Heartbreakers, that tonality we found that day between the keyboards and the guitar harmonics and the energy and the riffs.

That was the sound of our band. That's what we sounded like when we were at our best. And that's what we tried to do after that. That's the sound we worked for.

Going back to “The Boys of Summer,” that song was the result of you experimenting with a LinnDrum.

That's the way songs are. I wrote “Refugee” to a drum loop I got off of a record. “Here Comes My Girl” I wrote to a drum loop. I didn't have a drummer in my demo studio at home, so I would make drum loops before there were drum machines. That was just business as usual. Now I had this machine that will do the drum loop for me, but I could program it any way I wanted. I was just having fun with it.

One night I sat up – “I can play claps. I can play tom-toms. It’s all in a beat, now let me put some chords to it.” It was just an inspired moment. It could have been a drum loop, but it could have been anything. Songs come from everywhere.

“I gave him something that sounded like a Heartbreakers song, and he said, ‘That sounds too much like me. Go do something I can't do.’”

— Mike Campbell

You don’t shy away from the addiction problems that existed in the band. You write about your own trouble with cocaine and how you wound up in the hospital. That was your moment of clarity.

Yep. Your body will tell you when it's had enough. I was the same with drinking, too. I thought I was Keith Richards for a while there – “I can just have whiskey and play.” And then my stomach said, “Uh-uh. No, don't do that. I'm going to hurt you.” So I stopped. It wasn't hard to stop. It just didn’t work for me anymore.

Others weren’t so fortunate. You dealt with Howie Epstein and Tom’s drug problems quite differently. [Epstein was fired from the band in 2002 over his substance abuse.] With Howie, you confronted him directly and said he had to stop. However, with Tom, you took a more hands-off approach.

Howie and Tom were two different people, and they happened at two different parts in my life. When Howie was struggling, I did not understand addiction. I now do. I've been through Al-Anon. At the time that Howie was caught in his disease, I didn't get it. I was angry. I thought he was being stupid and disrespectful to the band. I didn't understand that he was sick, so I was angry with him and I dealt with it that way.

I told him I still loved him, but I just didn't have any patience for his behavior. By the time I had been through some stuff and learned more about addiction, I could see that it’s a disease and it's not a choice for some people. Then I had more compassion for Howie and what he had gone through.

Tom started struggling through his divorce and all, but I had a different relationship with him. I could go to Howie and say, “I don't like what you're doing,” and he might listen to me. With Tom, it was like “Your private life is yours, and mine is mine. I can see what you're doing, but out of respect for you, I'll trust you'll do the right thing. If you need me, call me.”

I could have gone to him and said, “Hey, you’ve got to cut this shit out,” which I kind of did once to the manager. But the thing with Tom was, you could say that and he would just look at you like, “But I'm Tom Petty. I'm going to do whatever I fucking want. Get out of my face.”

Those were the sides of his personality. He was intimidating, but there was love there. I think one reason we stayed together is because we kept our private lives separate. We didn't socialize that much off tour.

\When the tour was over or our studio time was over, I went to my world, and he went to his world. My kids, my family, his kids, his family. We would talk occasionally on the phone for an hour or two just to catch up, but we gave each other space. Tom made his own decisions about what he wanted even to the last tour.

That was his decision — he wanted to go on tour. Nobody was going to tell him no for any reason. We suggested to him that we could postpone the tour, but he said, “Nope, I’m doing this.” That was the end of it.

“Sometimes he made me so angry I couldn’t look at him.”

— Mike Campbell

Tom had hip problems that progressed to a broken hip, and to alleviate the pain he self-medicated. A week after the 2017 tour ended with the Hollywood Bowl show, he passed away. A lot of people in your position would torture themselves – “I should have gotten in his face.”

Well, I have no problem with that for the reasons I just explained. I don't torture myself. My conscious is clear because Tom knew that I knew, and Tom knew that I wasn't forcing him and getting in his face about it.

We had this invisible understanding, and I didn't have to confront him for him to know how I felt about it. Like I said, there was no second thoughts or reservations about going out on tour. In fact, the last conversation I had with Tom about it, I said, “Are you sure you want to do this? Are you up to it?” He said, “I'm not staying home. I'm going out. I want to do it. If I have to be in a wheelchair, I'm going to do it.” I said, “Okay, then what?” He said, “Well, when the tour's over, I'm going to go get my surgery. We'll write some more songs, make another record.”

That was the plan. It was kind of business as usual. I know that Tony, our manager, spoke to him and gave him options like, “We can postpone this. You can get your surgery now.” Tom said, “I need to be out there. I want to play with the band, and we're going to do it. I'll be okay.” So I have no second thoughts about it. I don't beat myself up like that. I miss them – same with Howie – but I did all I could.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.