"You only hit a wrong note if you leave the note by itself.” Michael Schenker talks soloing and technique in Guitar Player's May 1984 issue

The heavy metal guitarist spoke to us about guitar style, solos and why hearing “Michael Schenker is God” made him angry

This interview originally ran in the May 1984 issue of Guitar Player magazine.

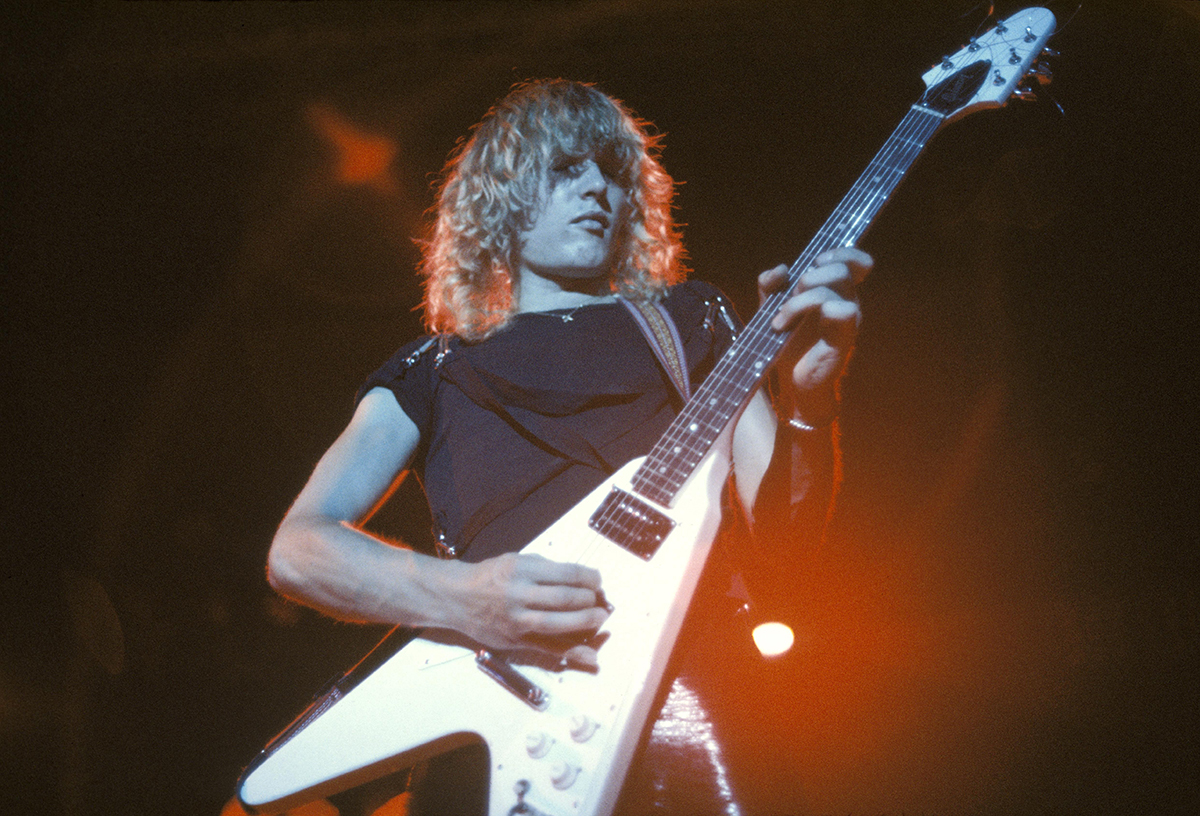

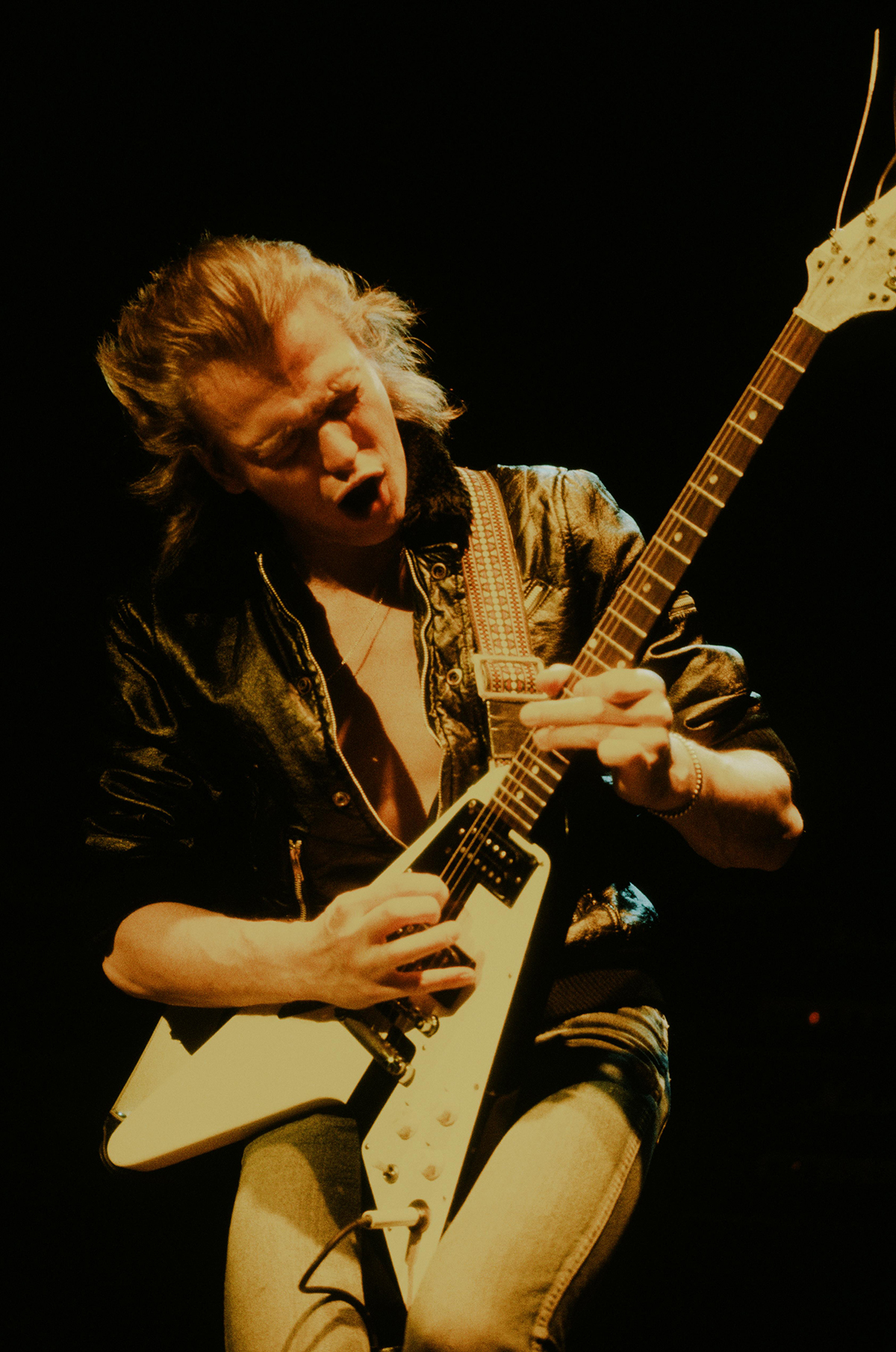

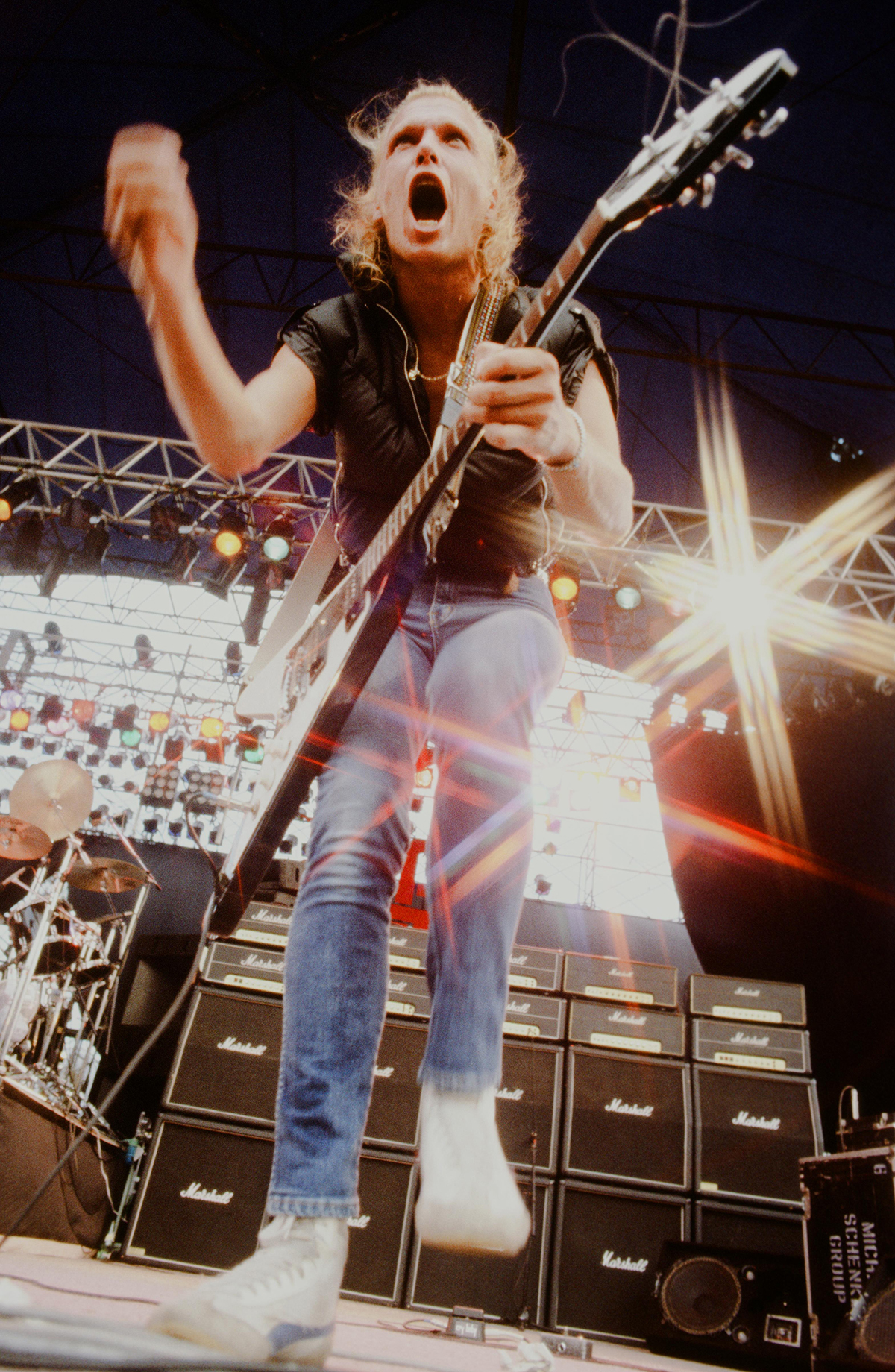

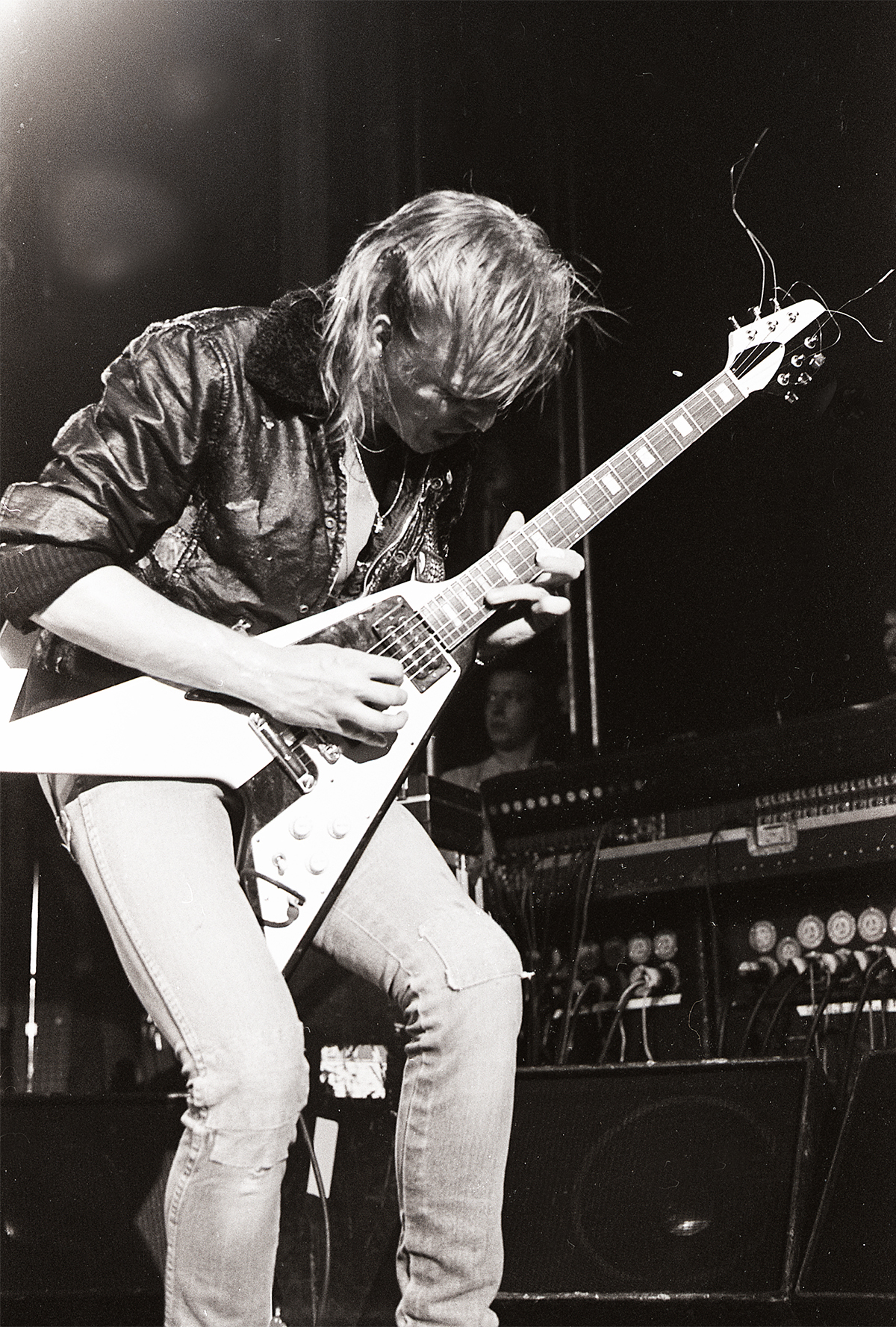

Michael Schenker stands at the forefront of continental Europe's heavy metal guitarists. An adept rhythm player with leanings toward sinuous hooks and full chords, the blonde with the Flying V electric guitar has earned most of his reputation as a soloist. His spontaneous approach uses speedy runs, growls, harmonics, sweeping finger vibratos and dramatic segues to carry statements in fresh directions. He often achieves a penetrating midrange tone with fluid sustain by keeping a wah-wah pedal partially depressed while soloing. On Michael Schenker Group albums, he double-tracks lines exactly or an octave apart to create thick, singing effects. Although musically unschooled, Schenker is among the most melodic and intricate players in heavy metal.

The younger brother of Scorpions guitarist Rudolf Schenker, Michael was born on January 10, 1955, in Sarstedt, a town 25 kilometers south of Hanover, West Germany. He began teaching himself guitar at age nine. Rudolf encouraged him by offering him a Deutsche Mark for each Beatles song he could figure out and teach him. At 11, Michael performed with his first band, Enervates, and afterward joined Cry. "We were the youngest beat band in Germany at the time," he recalls. "Everybody was under 14 years old." His next lineup, Copernicus, included Klaus Meine, present-day vocalist for the Scorpions.

By his mid teens, Michael was practicing four to eight hours a day. His goal, he says, was "to be able to play without thinking. At the same time, I felt it was very important to play fast as well as slow, and with a lot of feeling. I was always after a melody, even if I was doing catchy lines and fast runs.” Among those who inspired him were several Englishmen — Hank Marvin with the Shadows, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck — as well as one American, Leslie West of Mountain and West, Bruce & Laing.

Michael made his first recording at 15, playing on the Scorpions' 1971 debut album, Lonesome Crow. While the Scorpions toured throughout Germany during the next two years, four musicians across the North Sea were trying to slug their way up the English heavy metal heap as UFO. They had recorded two commercially unsuccessful albums in Japan and were about to tour Germany when, in 1973, guitarist Mick Bolton quit the band. UFO plunged ahead borrowing equipment and the lead guitarist from their opening act, the Scorpions. Impressed with Michael's solo abilities and creativity as a tunesmith, UFO invited the 18-year-old guitarist to become a full-time member.

Speaking little English, Michael needed an interpreter during his first months with UFO. Still, he contributed much of the music for the band's 1974 release, Phenomenon, including the riffs that helped make "Doctor Doctor" and "Rock Bottom" the band’s biggest hits. Schenker continued to refine his style during the next three albums — Force It, No Heavy Petting and Lights Out — taking larger solo spotlight and occasionally working in acoustic guitar textures.

Then, on the eve of an important U.S. tour, Schenker vanished without explanation. Paul Chapman was hired to substitute. (In his January '81 Guitar Player interview, Michael summed up his disappearance: "I was a bit errant and went on holiday and got myself straightened out.") The guitarist resurfaced after two months, rejoined the UFO tour, and recorded Obsession. The brilliance of his stage playing at the time was documented on a 1979 double-LP, Strangers In the Night. Finding it increasingly difficult to express his creativity, Schenker gave his two-month notice after the album's release and quit UFO for good.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As a favor to his brother Rudolf, Michael added several solos to the Scorpions' 1979 Lovedrive LP. He embarked on a series of European dates with the band, only to announce midway through the tour that he was leaving to pursue a solo career. His initial lineup of the Michael Schenker Group featured the rough-voiced Gary Barden, keyboardist Don Airey and a rhythm section acclaimed for its work with Jeff Beck: drummer Simon Phillips and bassist Mo Foster. The group booked London's Wessex Studios from May through July ’80 to record The Michael Schenker Group, which introduced the concert favorites "Armed and Ready" and "Cry For the Nations." Schenker and Barden co-wrote all of the material, with the exception of Michael's instrumentals, "Into the Arena" and "Bijou Pleasurette.” The album rates among the best work Schenker has ever done.

Only the writing team of Schenker and Barden remained intact for MSG, recorded in London and the West Indies during the spring of 1981. Paul Raymond, who had played with Michael on UFO's Lights Out, Obsession and Strangers in the Night LPs, came in on keyboards and guitar. Current band member Chris Glen took over on bass, and Cozy Powell provided drums.

The following year the Michael Schenker Group cut a live album in Japan, One Night at Budokan, that reached number three on the U.K. charts (the project has yet to be released in the U.S.). Afterward, Barden, Raymond and Powell left the band, and Schenker listened to over 700 tapes before recruiting Graham Bonnet as his singer, Ted McKenna, who had worked extensively with Rory Gallagher, took over on drums.

The revitalized lineup travelled to Le Chateau in France and Musicland Studios in Munich, Germany, to record Assault Attack. Schenker heightened the dramatic effect of the title track and "Desert Song" by multitracking lyrical, classically influenced solos into otherwise aggressive material. He also provided a searing guitar instrumental "Ulcer." After the session, Schenker and Bonnet had a disagreement during a warm-up gig for 1982's Reading Festival, and Gary Barden was brought back into the fold.( Bonnet has since become the voice of Alcatrazz.) Chrysalis Japan issued a deluxe Michael Schenker Anthology in 1983.

The Michael Schenker Group's latest release, Built to Destroy, showcases the guitarist's melodic sensibilities. Tracks of layered guitars create a symphonic effect in the instrumental "Captain Nemo." "Rock Will Never Die" highlights Michael's flair for dramatics, evolving from a flatpicked ballad into a screaming solo climax. Different mixes of the album have been issued in Europe and the U.S. The American version gives Andy Nye's lush keyboard textures a more prominent role. The album has peaked the charts in Japan and is selling steadily stateside.

The following interview took place earlier this year during Michael's opening West Coast appearances. Afterward, the band embarked on a tour package with Ted Nugent.

What should a Michael Schenker solo do?

It has to build. It's like a book, where you get an introduction, the highest point, and the happy ending or whatever. I like things that are melodic.

Some of your solos, especially in cuts such as "Assault Attack” and "Desert Song," sound as if they were separate compositions injected into the songs.

Yeah, you are right, actually. Do you remember any of our old songs, like "Try Me" [from UFO's Lights Out] or "Born to Lose" [UFO's Obsession]? They all used to be instrumentals, like a solo. When Phil Mogg heard them, they were guitar instrumentals. He just put his vocal to it. He used to just stick bits and pieces at the end and front. That's how I used to write all the time.

What led you to do a classical-sounding break in "Assault Attack" instead of a screamer?

Maybe I had too many screamers already. I try to balance the amount of different lead breaks.

Will you ever record completely different types of solos for the same song and then choose between them?

If I know what I want, then I wouldn't. But if I'm not quite sure what would sound better, then I maybe would try both. I think that was the case in "Assault Attack.” But usually my approach is the same as what I do onstage: improvise. I don't have much time to think. I just go for it.

How do you avoid falling into repetitious patterns?

I don't know. A repeat is part of a trademark. You have to repeat certain types of things because that's your style. How much you repeat is up to you. I don't think I repeat too much, but I don't know how I do avoid it. You just have to be careful.

Is it more difficult to record a fast solo than a slower, more classical one?

If it really has to be screaming and singing, I would say maybe that is more difficult. But then again, it depends what you expect from a clean sound. You can be lucky and just twiddle and you have got it straight away.

How do you psych yourself into playing your best in the studio?

I don't know. Just being very serious about it, I think. I just have to practice a bit, and then play. I have to work myself up to playing fast because that's what the fingers need. You have to warm them up.

What is involved in maintaining your level of skill?

I used to practice quite a lot, four to eight hours a day. I did the hardship when I was young — when you are supposed to do it. Now I'm just making sure I practice two hours a day outside of shows. I like to play between the soundcheck and when we go onstage. I just do whatever I like. When we are close to writing an album, I come up with licks all the time.

Do you ever get into slumps?

No. I'm happy with my playing. It might happen when I don't practice enough. I feel more satisfied when I practice a lot.

Will you ever spend a long period of time without picking up a guitar?

That does happen when I go on holiday or am ill or something for a week or so. When I come back and pick up the guitar, it's a very strange feeling. Sometimes I come out with very spontaneous, good things straight away. Often what I do alone is the same or very close to what I do onstage, except I don't play much to chords. I just play open solos.

Have you been exploring any new techniques?

No. I don't really look for any. I just like to stick with a plectrum and my guitar, and play normal.

Have you changed your recording methods since the first Michael Schenker Group album?

No. It goes into a microphone and into the mixing desk. I have left everything the same way. The music is always done first, and then the vocals.

On Built to Destroy, you've given keyboards a more prominent role than ever before.

Yeah. That is because Andy [Nye] has been involved in the songwriting. Because he writes songs on the keyboards, you hear more keyboards. Plus, the American mix of that album has got more keyboards than the European one, maybe. At least that's what I've been told. I haven't compared them both that much lately. If that is so, it's because Jack Douglas thought that would be the best idea when he directed the remix. I don't know about balance-wise, but sound-wise, overall I prefer the American mix.

Did you record with just Gibson Flying V's?

As far as I know, yeah, except for the middle bridge in "Rock Will Never Die," which was done with a Stratocaster. This was a quiet bridge, and Stratocasters have a good sound for that type of thing.

Do you use the same setup in the studio as onstage?

Yeah, everything is the same. I use 50-watt Marshalls and a Cry Baby wah-wah pedal, and I play loud. There might be other effects here and there, but I don't know all those names of things they have in the studio. There was something on the [flat-picked] beginning of "Rock Will Never Die." I think that was a mix between a flanger and something else. They took one signal of straight guitar to the board, and on a different track they recorded the signal with the effect.

Some of your solos on Built to Destroy seem a little shorter than usual.

I don't know. I was listening to UFO stuff a few months ago, and I think the difference is that I used to play a lot more in between vocal-like fillings — which I've left out a little bit, but I think they're coming back.

Do you rehearse solos before recording them?

If it's a tune where it's obviously worked out, then I have to learn it. This was about 20 percent of the last album. The rest of them are live [spontaneous]. If I do something in harmony, that's a signal that I worked it out and proved it. Sometimes these lines come out when you play, and if you are lucky, they come out at the same time you are recording. There might be one melody that you play by accident, which you might like so much that you try to learn that part and repeat it and maybe make something out of it. If I record a part like this two or more times, it takes what it takes. Like on that [cascading] part of "Systems Failing" — ! don't know if each line is double-tracked, but they are in harmony and octaves. On "Captain Nemo," the beginning, middle section, and end section are double-tracked.

What's important to keep in mind when you're double-tracking?

To play exactly the same twice. Obviously, how difficult this is depends on how difficult the part is you're playing. You have to make the parts up, and it's up to you how far you want to go, how tuneful you want to have the whole thing. It's up to you when you think you're satisfied with the sound before you put it on the tape.

Did you do much splicing as far as the other solos are concerned?

Apart from the worked-out bits, all the improvised solos on Built to Destroy were done in one go. This doesn't mean that they are the first takes, but the lead breaks you hear are complete lead breaks that were taped in one go. But it could have been the 10th one or whatever. I used to have, say, seven solos, and cut the best parts out of them and put it together — and the result was a terrible solo. But on this album I haven't done anything like that. I think it's the first time I've done it this way.

How do you judge which take to keep?

Say you can't make up your mind. The reason some people put them together is because they find something great in every break and try to connect them. But if you have got 10 lead breaks that are all a little bit different and good from beginning to end, you just try to pick the break which hasn't got something you have done before in a different song. It should be the one take that has everything, whatever you expect from yourself.

Do you move around as much in the studio as onstage?

No, I sit down most of the time. Of course, my playing sounds different when I'm sitting down.

Does your high onstage volume level ever influence the lines you choose? Can fast passages come across as well as slow ones?

The volume just gives you the sound. If you play louder, you.get more sustain. For a certain type of run or feel, you need a certain volume to do it right. Playing fast or slow is up to you, what type of sound you want.

Will you ever play something onstage that you've never tried before?

Oh, yeah. I try to do it all the time, here and there. I don't know how much chance you get to do this. Sometimes you want to, but you just go back into the same old trough. It depends on the mood you are in. Sometimes you feel in a risky mood; sometimes you don't.

What do you do when you play the wrong note?

If I can, I make up for it. You only hit a wrong note if you leave the note by itself. If you have the chance to to think good enough, you can connect the note which would be wrong by itself with another note that makes it the proper two notes to play together. This is what I do.

What guitar do you use most often for concerts?

The one I've been playing since I was 16: a [late-'60s] Flying V Gibson. I also have a spare V, which is a Gibson, and an Aria Flying V. I've got a Les Paul somewhere, but I never really use it. I have got that because I found sometimes I did need another guitar here and there for rhythm on previous albums. I still use it if I have to.

Do you often change your guitar and amp settings during shows?

On the 50-watt Marshall amplifiers, not at all. Everything is at 10, except the volume, which is at 8. But I'm using the Cry Baby wah-wah pedal like an equalizer. I have got my foot on it every time I play a lead break, and I move it in different positions. I also change the volume on the guitar — I go up and down for rhythms — and I change the pickup for whatever different lead break it is. My tone control is always on 10. On the lead breaks everything is on 10. For rhythms, my volume setting is on 10 or sometimes eight.

Will you change pickup selection as your solo moves from the low strings to higher ones?

No. I wouldn't change the pickup for the different strings. I would change the setting on the wah-wah pedal for the different strings.

What kinds of strings and picks do you use onstage and in the studio?

The picks are Hercos, the gray ones. usually follow an up-and-down picking pattern, or just downwards or up — it depends on where I am at. My strings are Fender Rock 'N Roll — from .009 to .042. I change the strings for every show. It's not unusual for me to break strings during a solo, either, so I do play with five strings quite often.

Do you ever experience tuning difficulties?

Yeah, because my guitar has been smashed many times, and it wasn't fixed very well. The cracks have been filled out with some material, and it doesn't stay in tune very good. It's not too bad, except when we are in a club and the temperature is hot. Then I have to tune a bit more.

Have you modified any of your Marshalls?

No. But some of them made in different years sound obviously different. Amplifiers can lose parts they used to have, or maybe little bits and pieces are changed. Over the years the comp any may change the people they get the parts from, and they'll get a different type of part that does the same job. But every little thing makes a difference in the amplifiers.

Sometimes you produce a vibrato effect that sounds as if it were done with a tremolo bar.

I do bend my neck. I press on the thing where you tune the headstock. I only do this when I play harmonics or open strings. If I press a string, I do it with my finger. [Ed. Note: Applying force to a guitar neck to create vibrato effects is not a recommended technique, since it could cause the neck to snap off.]

How many fingers do you use to bend a note — say, the G string at the 12th fret?

In that position I would use one finger the middle one. But if l go higher — like say the 22nd fret — and bend the E string, I would use two fingers for more control because they do slip away up there. I never bend with my little finger.

What do you listen to for pleasure?

I don't think I listen to music for pleasure. The only time I hear it is when other people listen to the radio and I have to be there. Also, it's my job, and I like to do things fresh. I like to be onstage and enjoy myself for as long as I can. If I listen to too much of what I'm doing myself, then I would be sick and tired of things much sooner.

Do you keep up with the latest heavy metal guitarists?

When people come out, some friends of mine or people who work with the group — like the road crew or whatever — might play it for me. I think Eddie Van Halen is a very good player. I also like Gary Moore, and the old ones, like Leslie West and Jeff Beck.

Do you feel any competition among heavy metal guitarists?

Competition? I don't think that should be even happening in the music business. It's not like you get a prize like the Olympics, where you get a medal if you jump higher than somebody else. Okay, you get a Gold album or you make more money if you sell more than others. But if you have got a festival with six groups playing, how do you do a competition? It doesn't bother me if I'm compared to other players. Everybody can do what they want to. If someone has got a reason for doing it, then it's good for them.

Do you think guitarists in general are getting better?

Yeah, I think that there are many more around and they seem to learn easier, but I'm just wondering about how original they are. An awful lot of people are picking up from the same person, and then what you hear in the end is about 50 players with very, very similar styles.

Do you perceive a difference between European and American heavy metal?

Yeah. The type of music they call heavy metal in America is different. Motörhead is how I think of heavy metal over in England, and in the States it doesn't have to be that rough. Heavy metal doesn't seem to be very musical in England — it doesn't seem very melodic. It just seems to be loud and rough.

Are American audiences different?

I wouldn't say it. If you didn't know you were in America, I don't think you would guess. Japan is the big exception for my market, and the rest all seem the same to me. America looks like a mixture of Europe — Spanish, German, Swedish, French and English people. If you were looking at an audience over here in America, it would seem as if you would put the whole of Europe together.

How would you characterize heavy metal from Germany?

I don't know. I don't know much about Germany anymore, because I got involved when I was 17 with the music scene in England. And since then I've only played like a whole tour once in Germany, and that was just a few months ago. But to be able to speak about the German audience, you have to be able to see different concerts to see something about how they react from an audience viewpoint.

At some of your recent concerts, fans have shown up in T-shirts with "Michael Schenker is God" printed on them.

I didn't see that, but I heard about that one when I was younger. I got used to the image of being a guitar hero — after all, it was my aim when I was young — but I got angry when people said, "Michael Schenker is God," because I was very sensitive about those things.

You frequently change personnel in your band. What do you look for in a vocalist?

Well, I liked Gary Barden's voice when I picked him. And once you pick musicians and play with them for a long time, you just get used to it. And then you just accept them as a voice. I still think he has a good voice . Still, there are better voices around and worse ones. But he suits me. I think [former band mate] Graham Bonnet is one of the best in the world. When I picked him, I imagined that that was it. But Gary has got many qualities that he didn't have — not just singing, but all-around.

What do you expect from your bassist?

I like Chris Glen just the way he is. I prefer bassists who are simple. I played with [Talas bassist] Billy Sheehan, and I think he is the best around. But he's more an acrobat. He's so clever that maybe he wouldn't be able to get a straightforward song together. It would be more messy if I had a bass player who didn't know where to keep simple. Some people play like a solo on the bass, and I think the bass in a song should be going with the rhythm. A lead guitar should do the things lead guitar is supposed to do, unless you call the bass a lead bass. If you have a screaming lead guitarist, you should have the exact opposite in your bassist.

Was One Night at Budokan a good representation of your live show at the time?

Yeah, it was very good. I hope to have it released in America sooner or later. I was aiming to have it out ages ago, but Chrysalis only wanted to bring out one single, and I didn't know which one I would choose. I wanted a couple of them out at the same time, or not at all . We just did some live recording at the Hammersmith in London, and maybe they will put the Budokan and the Hammersmith together in one package.

Has your band taped any videos?

No, but I think we are going to soon for "I'm Gonna Make You Mine." You need one over in this country.

What are your plans for the future?

Just to carry on and try to play wherever we can in America. Ten years from now, I would like to be doing the same thing I'm doing now if I feel the same.

What would you like to be remembered as?

I don't think that it's very important to me to be remembered.

What motivates you?

It's become a sort of routine, and I like the excitement. You have got a lot of advantages when you do play music. In the beginning, my aim was to be one of the best guitarists. As you get older, you also start thinking about philosophy, things like why do you live? You want to find other things as well once you have topped one aim. You also want to understand what life is all about. You connect more things together and aren't as extreme. It's not just music. There are more important things than music, but it's nice to have music with you while you are going your own way.

When are you happiest?

I used to think differently because I had to drink all the time before I went onstage, and now I don't. I'm happiest when everything is connected together as one piece. That's a very interesting thing, because if you want, you can connect the business with your private life and you don't even realize you're touring. After all, it's my profession, and instead of keeping it like, "Well, now I'm going to work, and now I'm coming home," I'm working and being at home at the same time all the time. Because I've got my fiancée with me, I've got my home.

What would you advise a young player who wanted to follow in your footsteps?

Once they have picked up their bits and pieces and tricks in a technical way, they should try to let their soul talk. Mix them all up, and bring your own character into your playing. Then people can put a name on your playing just by hearing you, without seeing your face.

Jas Obrecht was a staff editor for Guitar Player, 1978-1998. The author of several books, he runs the Talking Guitar YouTube channel and online magazine at jasobrecht.substack.com.