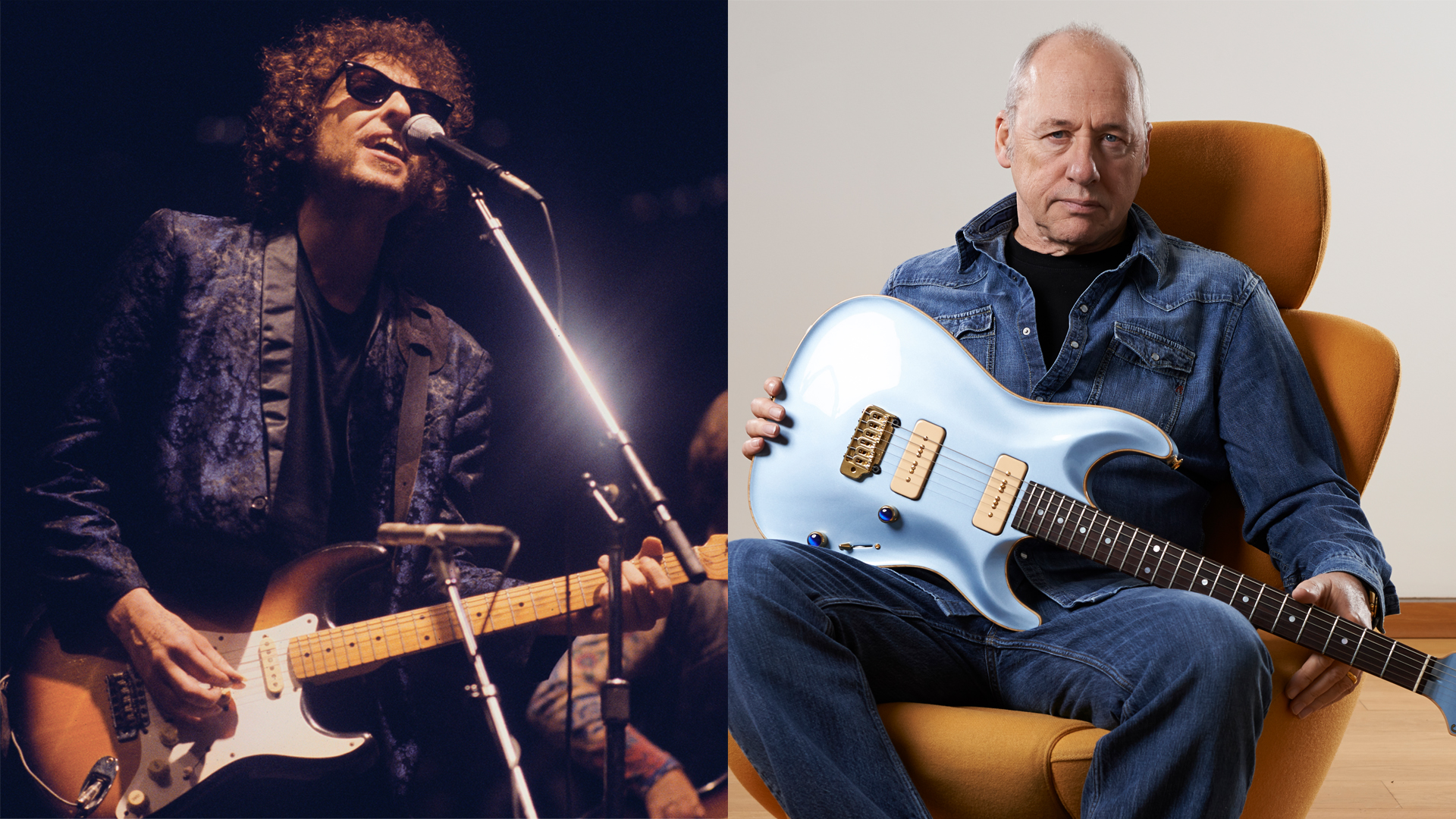

“That's enough to make anybody who writes songs want to retire." Mark Knopfler on his difficult collaboration with his childhood hero, Bob Dylan

The guitarist was at his peak with Dire Straits when Dylan hired him to produce 'Infidels,' the celebrated album that marked the born-again Christian's return to secular music

The saying “Don’t meet your heroes” is one worth heeding, particularly if you’re in the creative arts. The pure feelings we harbor for artists when they’re afar often become tarnished by exposure to the all-too human qualities they exhibit in person, often to extremes.

Producer Rick Rubin writes in his book The Creative Act: A Way of Being, “Many great artists first develop sensitive antennae not to create art but to protect themselves. They have to protect themselves because everything hurts more. They feel everything more deeply.”

Mark Knopfler found out as much when he had a chance to produce his boyhood idol Bob Dylan in 1983. The album he was selected for was Infidels, a record that found Dylan returning to secular music following three albums of songs inspired by his experience as a born-again Christian.

Knopfler had helped out on one of those releases, playing guitar on 1979’s Slow Train Coming, the first disc in Dylan’s “Christian trilogy.” The album arrived shortly after Knopfler’s own ascendency to guitar hero status courtesy of Dire Straits’ 1978 self-titled debut and its hit song, “Sultans of Swing.”

“I was hugely influenced by him about the age of 14 or 15,” Knopfler told Dan Forte in an interview published in Guitar Player’s September 1984 issue. “I heard Bob Dylan from the very beginning, the ‘Hard Rain’ days, and went with him all the way up, and I'm still with him. I still think he's great. Blood on the Tracks is one of my favorite records.”

It’s a remarkable sentiment given that Dylan had put the guitarist through the ringer just one year before, while making Infidels. The former folk icon selected Knopfler to produce him after considering and rejecting David Bowie, Elvis Costello and Frank Zappa. Dylan felt inexperienced in the modern recording studio environment and needed someone who was up to speed with technology. His trio of rather bizarre choices suggests he was also looking to make a sea change in his musical approach and sound.

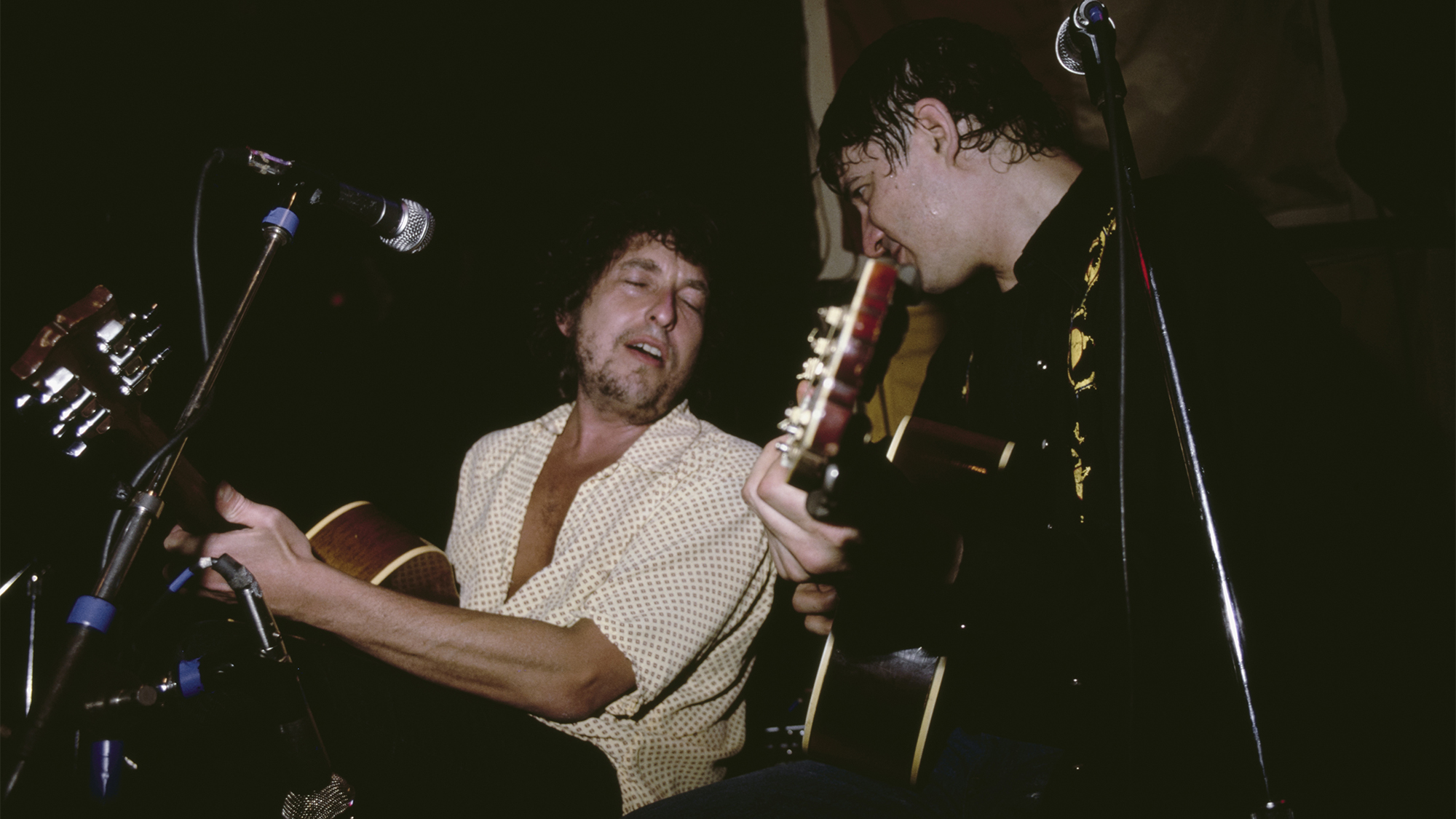

As it turns out, the songwriter had pretty much sewn things up on his own before Knopfler arrived and recording began at the Power Station in New York City, in April 1983. It was the first inkling Knopfler had that he would not be driving the sessions as much as navigating them, guiding the players through Dylan's temperamental fluctuations.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Dylan's choices for band members dictated Infidel’s strong rhythmic vibe and highly polished style. For the rhythm section he hired bass guitarist Robbie Shakespeare and drummer Sly Dunbar, a tandem better known as Sly & Robbie who found fame both as producers and as Island Records recording artists, where they also produced acts like Black Uhuru, Wailing Souls and Grace Jones.

Dylan had likewise selected former Rolling Stones lead guitarist Mick Taylor, possibly before choosing Sly & Robbie. The two had met the previous summer, and Dylan had begun showing him his new songs months before recording began.

Knopfler, for his part, brought in keyboardist Alan Clark and engineer Neil Dorfsman, who had worked on Dire Straits’ 1982 album, Love Over Gold, and Knopfler’s soundtrack for the movie Local Hero. As one of the album’s musicians, as well as its producer, Knopfler was paired with Taylor, who played slide guitar for much of the record.

The result was the sound of two virtuosos lending their fluid electric guitar chops to what many consider to be one of Dylan’s best albums from his later catalog. Combined with the strongly syncopated rhythms of Sly & Robbie, they helped Infidels achieve a remarkable, and successful, shift in style for Dylan, as exemplified by standout tracks like “License to Kill,” “Neighborhood Bully,” “Sweetheart Like You” and the stunning lead track, “Jokerman.”

“I suggested Billy Gibbons, but I don't think Bob had heard of ZZ Top,” Knopfler told Guitar Player. “It would have been great to have done that with Billy.”

As Knopfler would soon find out, working with his hero was anything but smooth. Dorfsman’s recollections of the sessions are vivid and excruciating.

“I don’t want to use the wrong word, here, but Bob was also a little bit of an agent provocateur, or he even had a little saboteur in him,” Dorfsman told Uncut. “If things were going maybe too well, in somebody else’s definition, he would consciously make an effort to make that stop.”

On one session, Dylan took the tinfoil wrapper from the sandwich he’d had for lunch and began flexing it, accordion style, into the microphone. ”It was just his way of saying, ‘I’m bored with this, I don’t want to do this particular song anymore,’” the engineer recalled.

I don’t want to use the wrong word, here, but Bob was also a little bit of an agent provocateur, or he even had a little saboteur in him."

— Neil Dorfsman

Dylan also announced one night that he wanted to start recording a Christmas album immediately. “We all laughed, thinking, He’s just messing with us,” Dorfsman said. “But, of course, years later, he subsequently came out with a Christmas record. It was kind of intimidating, challenging, but also hilarious in its own crazy way.”

Tasked with keeping the sessions running smoothly, Knopfler found himself frustrated at how differently it was going from what he had initially imagined.

“I know that it really, really bothered Mark, that song choices were dictated a little bit, and were turning out to be different from the song choices he thought we were going in to do,” Dorfsman said. “I could feel the air just sort of going out of Mark a little bit, when he realized that the traditional role of the producer was not going to be in play on this record... I’m sure it was very frustrating to Mark.”

Knopfler admitted as much — albeit with admirable diplomacy — when speaking with Forte for Guitar Player.

“Was it difficult producing Dylan?”

“Yeah. You see people working in different ways, and it's good for you. You have to learn to adapt to the way different people work.

“Yes, it was strange at times with Bob. One of the great parts about production is that it demonstrates to you that you have to be flexible. Each song has its own secret that's different from another song, and each has its own life. Sometimes it has to be teased out, whereas other times it might come fast. There are no laws about songwriting or producing. It depends on what you're doing, not just who you're doing. You have to be sensitive and flexible, and it's fun.

“I’d say I was more disciplined. But I think Bob is much more disciplined as a writer of lyrics, as a poet. He's an absolute genius. As a singer — absolute genius. But musically, I think it’s a lot more basic. The music just tends to be a vehicle for that poetry.”

I’d say I was more disciplined. But I think Bob is much more disciplined as a writer of lyrics, as a poet.”

— Mark Knopfler

Regardless of the trials he endured, Knopfler maintained his love for Dylan’s work on the album, particularly the song “I and I.” He was particularly moved by the song’s first lines: “Been so long since a strange woman has slept in my bed / Look how sweet she sleeps, how free must be her dreams / In another lifetime she must have owned the world or been faithfully wed / To some righteous king who wrote psalms beside moonlit streams.”

“To hear the first lines of ‘I And I,’ that's enough to make anybody who writes songs want to retire,” Knopfler told GP. “It's stunning.

“Bob's musical ability is limited, in terms of being able to play a guitar or a piano,” he explained. “It's rudimentary, but it doesn't affect his variety, his sense of melody, his singing. It's all there. In fact, some of the things he plays on piano while he's singing are lovely, even though they're rudimentary. That all demonstrates the fact that you don't have to be a great technician.

“It's the same old story: If something is played with soul, that's what's important. My favorite records, by and large, aren't wonderful technical achievements, with the exception perhaps of people like Chet Atkins. But generally speaking, all you've got to do is listen to a Howlin' Wolf album. That's just soul.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.