"You bury the pick with your thumb and you have all the room you need." Leslie West revealed the picking techniques that made him a singularly great guitar hero to Eddie Van Halen, Randy Rhoads and Pete Townshend

Speaking to Guitar Player in 1972, the Mountain guitarist laid out his use of "harmonic jumps" and high volume to achieve a wide range of articulations

“I’m no great guitarist technically,” Leslie West once said, “but you wanna know why people remember me? If you take a hundred players and put them in a room, 99 of ’em are gonna sound the same.

“The one who plays different…that’s the one you’re gonna remember. I learned that you should think about the song, think about the chords you’re playing behind. Most of my solos come right out of those chords. You play the notes within the chords and try to pick a melody from there.”

Long before Eddie Van Halen, Randy Rhoads and Michael Schenker arrived on the guitar scene, each of these three transformative rock guitarists was tuned into West’s guitar work. The Mountain guitarist was a singular force in early 1970s rock, with a style and tone all his own. It even made fans of his contemporaries like Pete Townshend, who at one point enlisted West to help on early sessions for the Who’s 1972 album, Who’s Next. Like the best electric guitar stylists rooted in the blues, West peeled off economical single-note lines as memorable as any melody, using his picking technique and frequent use of pinch harmonics to add interest or drive home the tail end of a line or solo.

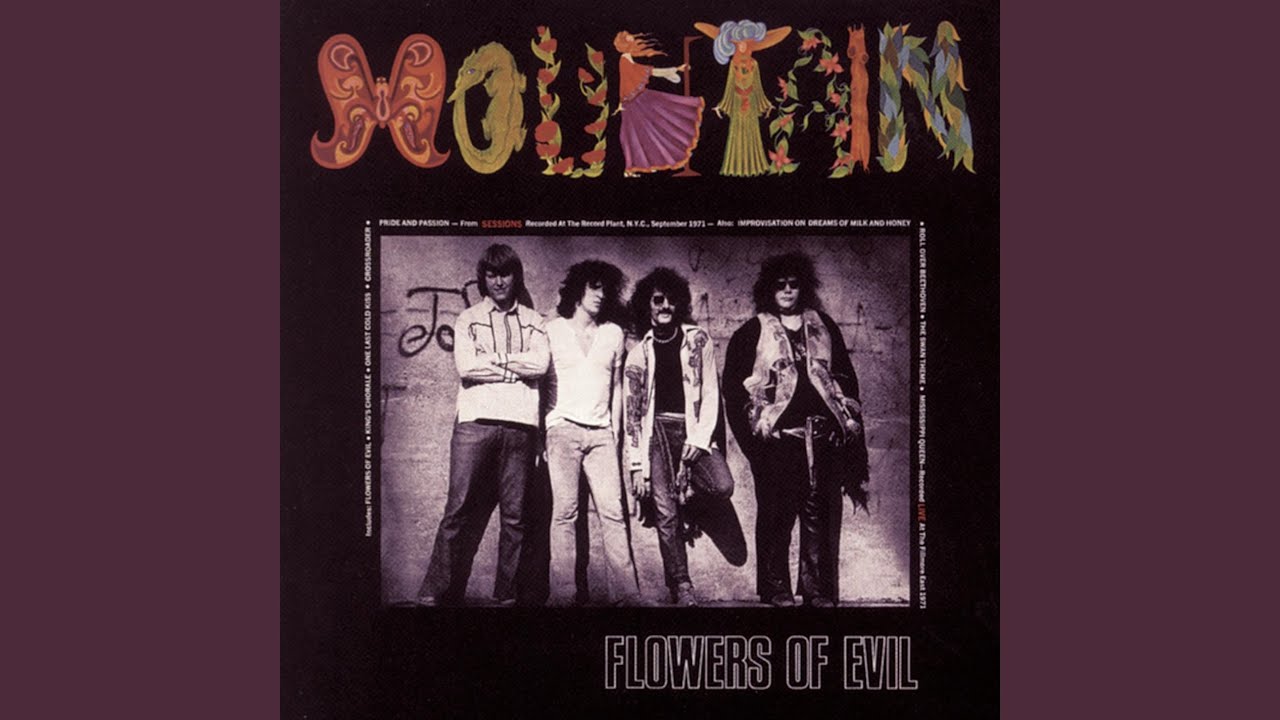

West arrived on the blues-rock scene in 1969 with his solo album, Mountain, a long-player created with the help of bassist and producer Felix Pappalardi, who was fresh from his years producing Cream. West and Pappalardi would use Mountain as the springboard and name for their own band, which would go on to create such timeless tracks as “Mississippi Queen,” “Theme for an Imaginary Western” and “Nantucket Sleighride.”

While Mountain’s music was a yin-yang mix of West’s gutbucket blues rock and Pappalardi’s prog-inspired balladry, what was common to all of it was West’s guitar, overdriven and snarling as he unloaded lines and solos unmistakable from any other guitarist's, giving each track never more than it needed while imbuing each note with plenty of heart and soul.

What made West’s guitar lines so memorable was not only his note choices but his distinct way of picking and articulating them. As he explained to Guitar Player in our April 1972 issue, his stinging lead tone and frequent use of natural harmonics came down to his method of picking.

“When I use a pick — and I use one most of the time — I try to bury it between my thumb and my first finger and just let a little bit of the corner stick out,” he explained. “I can make a string jump harmonics that way. Albert King does that without using a pick; he uses his thumb.

"It really is a great sound, because if I'm playing along like, say, on the B string and all of a sudden I want a note that will really stick out and be an important part of the phrase, I can make a note jump an octave, and it is really effective."

A good example of West's ringing harmonic technique is the last note of his solo in the middle section of "Theme for an Imaginary Western,” from the album Climbing! West would rest the side of his right hand's palm on the bridge or on the strings he wasn't picking, but his technique seldom allowed his hand to remain stationary for long. Along with the pick, he occasionally used his third finger for double picking.

In his early years with Mountain, West’s main studio guitar was a single-cutaway Les Paul Junior with a single P90 pickup. (For performances, he also used a Gibson Flying V and a Dan Armstrong Plexi set up for slide.) As West said of the Junior, the space provided by having just one pickup was useful for his pinch harmonics. “You gotta have the Junior to do ’em right, because of the single pickup,” he explained once while demonstrating his technique. “See the way the strings can bend down when you hit ’em? If there was a neck pickup, it’d be in the way. You bury the pick with your thumb and you have all the room you need.”

Unable to find extra-light string sets in those early years of rock guitar's dominance, West strung his guitars with standard sets of La Bella strings, substituting a .010-gauge banjo A string for the high E and moving the other five strings down one position.

West was also adept at bringing other techniques into his playing. For the instrumental prelude to Mountain's “Pride and Passion,” from Flowers of Evil, he used a hammering technique with his left hand that produced a "violin sound — like what Segovia does,” he said. “You can do it in rock and roll too." To demonstrate for the interviewer, he hammered on a string and then turned up the volume of the guitar. As he explained, the metallic sound of the string rattling against the fretboard was never amplified, and West could control the intensity of the sound by adjusting the guitar's volume knob.

For the prelude to "Pride and Passion," West tuned every string to the same note, or that note's octave, and then played the instrument bottleneck-style through an echo unit. "It sounds like a string section," he said. "I figured that if I can make a guitar sound like a violin, why not make it sound like a couple of violins." The same technique on the low strings would allow him to produce a cello-like sound.

West would also use his "harmonic jump” technique with his guitar at full volume to produce seemingly infinite sustain, as he did during the guitar solo of "Dream Sequence" on Flowers of Evil.

"The note catches, man," he told Guitar Player. "There is a feeling you get; you can feel as soon as you hit the note if it is going to go into that sustain. You can hold it for days if your guitar is wide open."

Notably, West hadn't used a fuzz tone in four years when he spoke with Guitar Player in 1972, preferring to use his amp volume and hands to get all the dirt and sustain he required.

Combining that with his sweet, smooth finger vibrato, West created a guitar voice like none other. "Vibrato is all in control; it's like a voice, you know.," he explained. "Some opera singers control their voice to get that slow vibrato. Eric Clapton has got about the best vibrato I ever heard in my life. Hendrix and Mick Taylor have beautiful vibratos too. I'd take these guys over anybody else because they control the whole thing. Some guitar players hit a note and go into a vibrato that's really fast and intense with no control, and it sounds like an opera singer with a bad voice."

Perhaps the ultimate proof of West’s power is not that he influenced guitarists at the peak of his early fame but that he continues to years after his death on December 23, 2020. Consider Grace Bowers: Just 18, the gifted guitarist cited Mountain’s Climbing! as one of the 10 records that changed her life, calling out West’s guitar solo on “Theme for an Imaginary Western” as “one of the most perfectly crafted guitar solos ever. His tone — not even just on this album, his tone in general — was so good. He's one of those players you can recognize right away. It's that distinct.” If young players like Bowers are tuning into him, there is perhaps no greater proof of Leslie West’s indelible power and influence in guitar.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“I was home with the family and I got a phone call saying, 'You've won a Grammy.' We were like, 'You've got to be kidding?'” Martin Barre recalls Jethro Tull’s famous Grammy triumph over Metallica 36 years on

“F****d me up completely. I couldn’t make head or tail of it.” Eric Clapton on the one guitarist who blew him away onstage