“I just want it known I'm allowed to put four songs on the album, whatever happens.” John Lennon had a plan to keep the Beatles going into the 1970s. Paul McCartney rejected it. The rest is history

A last recorded meeting between Lennon, McCartney and George Harrison revealed how they might have carried on despite their growing differences

As most Beatles fans know, John Lennon quit the group first, on September 20, 1969, bringing the Fab Four to what most would agree was an untimely end.

What many don’t know is that just two weeks before he announced his departure, Lennon proposed that the group record another album as well as release a new single in time for the holidays.

The evidence for this comes from a tape recording made on September 8, 1969, at Apple Corps headquarters in London, of a meeting between Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison. The recording exists simply because drummer Ringo Starr was unable to attend. He’d been taken to the hospital with intestinal complaints — Starr had a history of abdominal ailments and food allergies — and the recording was made for his benefit.

“Ringo,” Lennon explains on the tape, “ you can’t be here, but this is so you can hear what we’re discussing.”

But as the tape shows, Lennon wasn’t merely thinking about one more Beatles album and single — he was planning a future strategy for the group.

The key evidence is his plan for how he, McCartney and Harrison — the group’s main songwriters — would share space on future albums. He planned that each of them should be allowed four songs per album, with another two available for Starr, if he wished.

“Ringo, you can’t be here, but this is so you can hear what we’re discussing.”

— John Lennon

“When we get into the studio, I don't care how we do it, but I don't want to think about equal time,” he said. “I just want it known I'm allowed to put four songs on the album, whatever happens. I don't have to say, ‘Should we do it now?’ because I think we'll all get fed up in three weeks, or actually the album will be full because we did two of Paul’s last week or one of Ringo's or one of George’s, whatever, and, well, it's too late now. Next album.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Lennon was also eager to abandon what he called “the Lennon and McCartney myth” about their songwriting partnership. While the two men had occasionally written together in the past — going back to their earliest days as teens struggling to play acoustic guitars — they mostly composed alone. Despite this, each of their songs was credited to Lennon-McCartney, regardless of who wrote it. Lennon suggested that, moving forward, only the sole writer should get credit.

One might think McCartney would have been thrilled by the suggestion to record a new album. He’d been despondent over Lennon’s lack of interest in the group and had singlehandedly corralled the Beatles and their producer, George Martin, back into the studio to record Abbey Road earlier that summer.

But he said very little in the meeting, aside from rejecting Lennon’s suggestions for a more equitable division of songs and a more accurate assigning of songwriting credits.

Lennon’s suggestion to give Harrison a larger share of each album’s real estate was in recognition of the younger guitarist’s growth as a songwriter. Over the previous year, Harrison had contributed “Old Brown Shoe,” “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun” to the group’s catalog, each song as good as anything Lennon or McCartney created.

The Beatles felt strongly enough about “Old Brown Shoe” that they made it the B-side of their single “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” released the previous May 30. As for “Something,” it would become Harrison’s first, and only, Beatles A-side (albeit a double A-side) when it was released with “Come Together” on October 6, 1969.

I mean, we’ve never offered George B-sides; we could have given him a lot of B-sides, but because we were two people, you had the A-side and I had the B-side.”

— John Lennon

The fact that Harrison could score placement on two singles within a matter of months, while McCartney was left out in the cold, was proof that he had become a stronger songwriter and that, more over, his bandmates and producer had taken note.

“We always carved the singles up between us,” Lennon said to McCartney. “We have the singles market, [George and Ringo] don’t get anything! I mean, we’ve never offered George B-sides; we could have given him a lot of B-sides, but because we were two people, you had the A-side and I had the B-side.”

It’s also possible that Lennon was thinking about Harrison’s abrupt decision to quit the group the previous January 10 during a dustup with McCartney while making Let It Be. Following Harrison’s departure, Lennon and McCartney had a conversation, recorded without their knowledge at Twickenham Film Studios, about what Lennon referred to as the "festering wound" of Harrison’s discontent after years of having his songs ignored. As Lennon saw it, Harrison’s resignation wasn’t a sudden decision but the inevitable culmination of years of feeling marginalized.

As a way to find the best songs for their future albums, Lennon suggested they give away tunes that would be better suited to other performers. All three had already doing this to some extent: Lennon had released “Give Peace a Chance” with his and Yoko Ono’s Plastic Ono Band project; McCartney had given his songs “Goodbye” and “Come and Get It” to Apple Records artists Mary Hopkins and Badfinger, respectively; and Harrison had passed his White Album reject “Sour Milk Sea” over to Apple signee Jackie Lomax.

In making his argument, Lennon specifically mentioned McCartney’s “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” a pair of old-timey singalong tunes Lennon was known to have reviled.

"Wouldn’t it be better — because we didn’t really dig ‘em, you know? — for you to do songs that you dug and for ‘Ob-La-Di’ and ‘Maxwell’ to be given to people who like music like that. Like Mary [Hopkins] or whoever it is that needs a song. Why don’t you give that to them?

"The only time we need something vaguely of that quality is for a single, and for an album we can just do only stuff that we really dug. It’s a drag to put that song on an album that nobody dug, including the guy who wrote it, just because it was going to be popular. ‘Cause the LP doesn’t have to be popular in that way.”

In fairness, McCartney never said he didn’t like either song, but Lennon’s point was clear: The Beatles should choose the material most representative of them as a collective, rather than serve as each other’s backing band, a practice that had begun with the White Album and continued during the making of Abbey Road, in particular with “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and McCartney’s side-two medley.

Sadly, rather than discuss the merits of Lennon’s suggestions, the three Beatles descended into discussions about Harrison’s songwriting — McCartney said his tunes had only improved that year, while Harrison argued that they’d been written even earlier — and whether or not Lennon had participated enough in recording Harrison’s songs.

“Most of my tunes, I never had the Beatles backing me,” Harrison falsely complained.

“Oh, c’mon, George! We put a lot of work in your songs, even down to ‘Don’t Bother Me,’” Lennon responded, referring to Harrison’s first song, which appeared on 1963’s With the Beatles. “We spent a lot of time doing all that, and we grooved. I can remember the riff you were playing, and in the last two years there was a period where you went Indian and we weren’t needed!”

Oh, c’mon, George! We put a lot of work in your songs, even down to ‘Don’t Bother Me.’ And in the last two years there was a period where you went Indian and we weren’t needed!”

“That was only one tune,” Harrison said. “On the last album [the White Album] I don’t think you appeared on any of my songs. I don’t mind.”

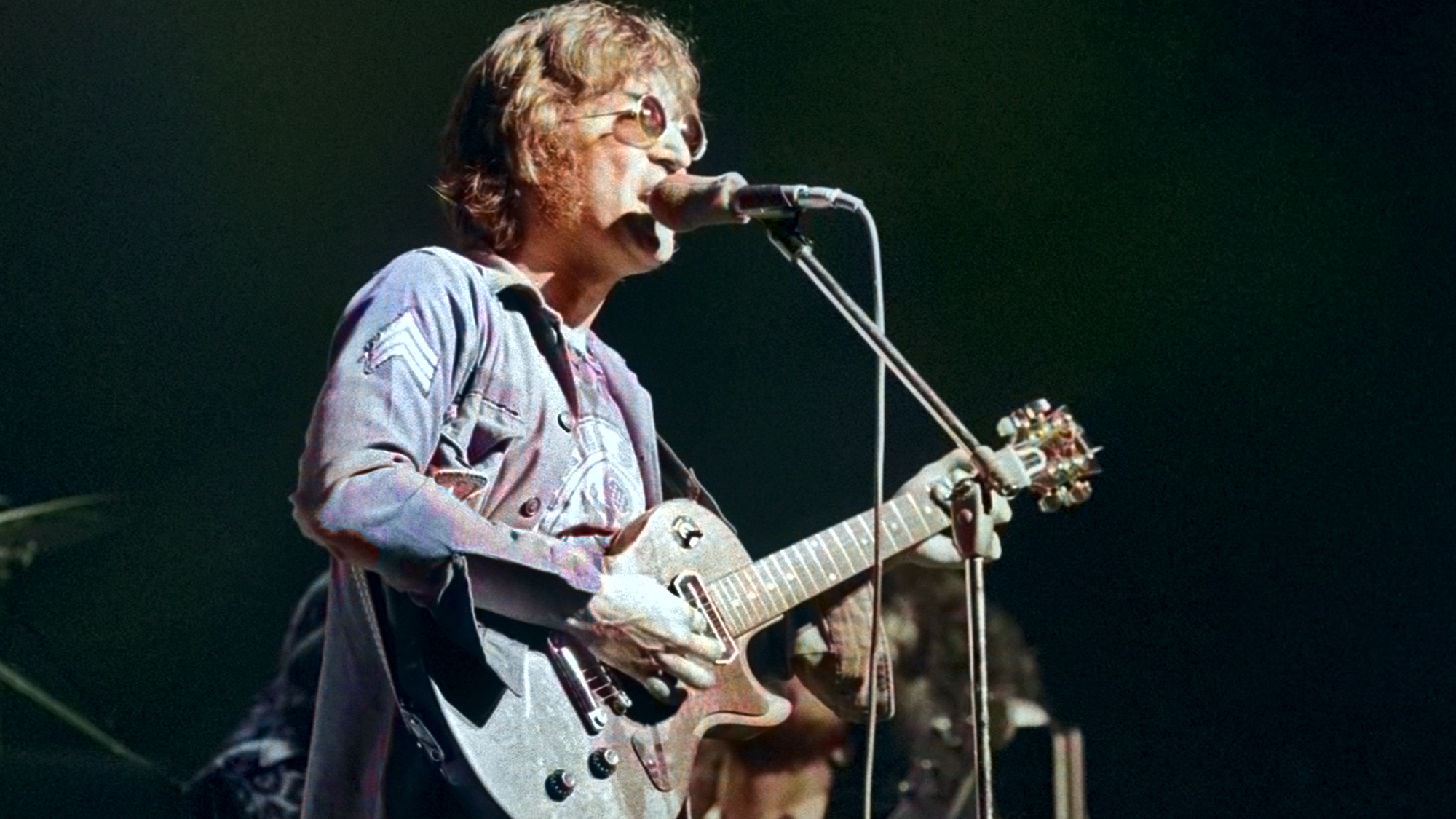

“Well, you had Eric, or somebody like that,” Lennon replied defensively, referring to Eric Clapton’s electric guitar contributions on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” recorded with Harrison’s “Lucy” 1957 Gibson Les Paul.

It’s remarkable that neither Harrison nor McCartney seemed to grasp that Lennon was, for the first time in at least a year, showing his commitment to the group’s future.

It was a missed opportunity. Soon after the meeting, Lennon and Ono departed for a September 13 performance at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival Festival with an ad hoc Plastic Ono Band lineup featuring Clapton, bass guitarist Klaus Voormann and drummer Alan White.

By the time they returned, Lennon wanted out. On September 20, 1969, he told his bandmates he was quitting. The Beatles’ last chance to stay together had passed.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.