“Eric thought he was going to have this little blues trio and be like Buddy Guy. We had different ideas." Jack Bruce on how Eric Clapton was the odd man out in Cream

Bruce said the band's label saw Cream as a quick cash grab and had no idea the group would be as influential as it was in England and abroad

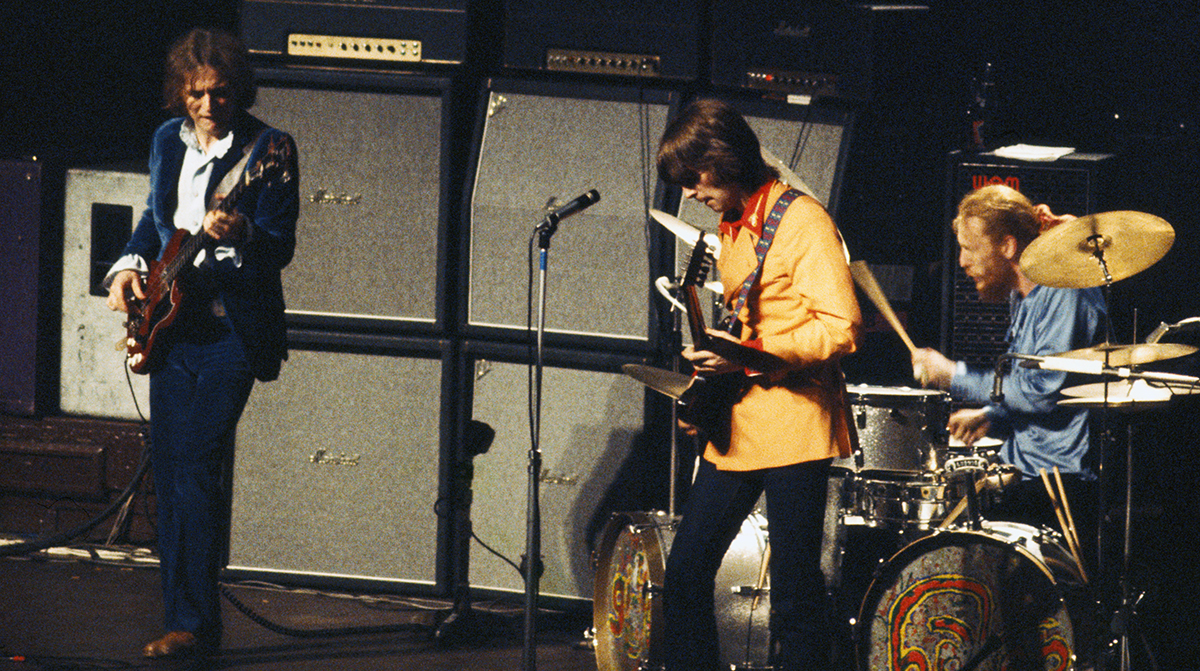

Cream were a revelation when they emerged on London's blues scene in 1966. Until the power trio's arrival, blues guitar had typically been slow, intentional and emotional. Unlike others before them, Cream — Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker — brought rock and roll fire, flair and ferocity to the genre — along with a fair helping of jazz-inspired jamming — and in doing so helped change the game.

Yet despite comprising three superlative musicians — including Clapton, who had forged a formidable reputation with John Mayall's Bluesbreakers — Bruce believes the group was, from its start, destined to pull itself apart.

His comments — from a 2012 interview with Guitarist conducted two years before his death — centered on the supergroup’s creative apex, 1967’s Disraeli Gears.

“I think Eric thought he was going to have this little blues trio and he would be sort of like Buddy Guy standing out the front," Bruce offered. "And then I thought, Great, I can be a composer and get some songs out there. And I think Ginger just wanted to conquer the world, basically, like Genghis Khan or somebody. We had different ideas.

“Meanwhile, the management was thinking, ‘Let’s milk this for all it’s worth because it ain’t going to last. So let’s get them out there and make them play every toilet in the US for as long as they’ll last before they go barmy or kill each other.’”

What management never imagined, according to Bruce, is that Cream would not only become an influential blues-rock crossover act but also cross the pond and catch fire in America.

“[They] thought it was going to be an all-star band that would fill the blues clubs, and maybe be a nice festival attraction,” Bruce said. “They never thought it would spread; they never thought it would get to America; they never thought we’d have hit songs. They had absolutely no bloody idea. And when you look at it, it’s a miracle that it happened.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Bruce was certainly correct about Clapton's aims. Seeing Buddy Guy perform live at London's Marquee Club in 1965 inspired him to sever ties with the John Mayall's Bluesbreakers and launch his own group.

"What [Guy's performance] said to me was 'This was possible,’” Claton recalled of the change-making show decades later. “If you were a good enough guitar player, you could do it as a trio. It seemed to be so free, you could go anywhere. With Jack in my filing cabinet, I was thinking about that as a way of breaking free.”

But Clapton's Guy-inspired foundation would form just one facet of the group's musical direction. Bruce was eager to take the blues to new places.

“Eric was really into the blues and he knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t know," the bassist said. "So I was being a bit presumptuous by saying, 'I love the blues', but I’d want to take it a step further and use the language of the blues as a way to write music for us. I always thought I could really change the world through music.”

in fact, both Bruce and Baker had jazz backgrounds, unlike Clapton. The late Peter Brown, who co-wrote lyrics to Cream songs like "White Room" and "Sunshine of Your Love," believed that helped Clapton elevate his playing to new heights.

“They didn’t put Eric down,” he said of Bruce and Baker. “They didn’t say, 'You don’t know enough about chords, or, You don’t know enough about jazz to play with us.' What they did say was: 'You’re a terrific player with terrific feeling, and if you play with us then this thing will happen. The magic will come.'”

The magic came and went, with Cream disintegrating after four studio albums, leaving behind an untouchable legacy.

Reflecting on what they left behind, Bruce mused, “I think you always would like another go.

“You’re never quite happy about it,” he said. “There’s definitely things that could be changed and, obviously you only hear the mistakes. But once it’s finished, it’s finished.”

A freelance writer with a penchant for music that gets weird, Phil is a regular contributor to Prog, Guitar World, and Total Guitar magazines and is especially keen on shining a light on unknown artists. Outside of the journalism realm, you can find him writing angular riffs in progressive metal band, Prognosis, in which he slings an 8-string Strandberg Boden Original, churning that low string through a variety of tunings. He's also a published author and is currently penning his debut novel which chucks fantasy, mythology and humanity into a great big melting pot.