"When it comes to playing, if you do it well and keep at it, somebody is going to appreciate it.” B.B. King on the night in 1967 when he jammed with Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix in New York City

The night marked the moment King recognized his influence on the new generation of blues guitarists — but he had no bitterness for his years in obscurity

B.B. King had enjoyed a long friendship and musical relationship with Eric Clapton prior to his interview with Guitar Player in the October 2000 issue. That year he and Clapton released Riding With the King, their first collaborative album, a number-one entry on Billboard’s’ Top Blues Albums chart and the winner of the 2001 Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album. He told us how Clapton and his fellow guitarists in the British blues boom opened the door for his success, and gave us insights into the night in 1967 when they jammed in New York City.

“In the early years, I thought that everybody seemed to get a break but me,” B.B. King tells Guitar Player. “I wasn't bitter about it, I figured they got a break because they deserved it. But I thought I did, too.”

B.B. King’s name, face, music and heavenly finger vibrato were known far and wide long before the 20th century came to a close. But for the first half of his life, King toiled in near obscurity. His recording career was sustained largely by occasional hit singles on the U.S. R&B chart. He released 13 albums before one of them — 1968’s Blues on Top of Blues — reached any U.S. chart. It hit number 46 on the U.S. R&B roster. Its follow-up, Lucille, released later that same year, marked his first appearance on the Billboard 200 Albums chart.

It was but a prelude to what came next. As 1969 arrived, King kept busy, releasing a pair of albums that would make him an institution unto himself. The first, Live & Well, became his first album to crack the Top 100. The second, Completely Well, soared to number 38, reached number five on the R&B chart and earned King a Grammy for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance. It also gave him a hit with the tune that will forever be his signature song, "The Thrill Is Gone."

King acknowledges his hard-won success was helped along by the popularity of the British blues boom.

“Finally — finally — when the kids started to play blues, they opened up a lot of doors for B.B. King,” he says. “I pray on it sometimes, and I say, ‘Thank God—better late than never.’ ”

But to make it through those years of obscurity, B.B. explains, it took a positive outlook.

“I was never bitter,” he offers. “I don't feel I have a reason or a right to be bitter. No, I didn't get the recognition that I thought I deserved, but why should I be bitter about it? You can't make people love you.” He laughs. “They love you if they want to. When it comes to playing, if you do it well and keep at it, somebody is going to appreciate it.”

Rather than pass blame onto others, B.B. accepts that, if there is a fault, it’s his own.

“When I feel that I'm not recognized now, I figure a lot of it has to do with what I didn't do back then, or what I'm not doing today,” he says. “That's the way I see it. Sure, anytime you're in a lineup trying to get a job and someone else gets picked, you wonder, Why didn't they pick me? But that's the way life is.”

As B.B. acknowledges, a new generation discovered him in the late 1960s after guitarists like Eric Clapton and Keith Richards began singing his praises, alongside bluesmen like Muddy Waters.

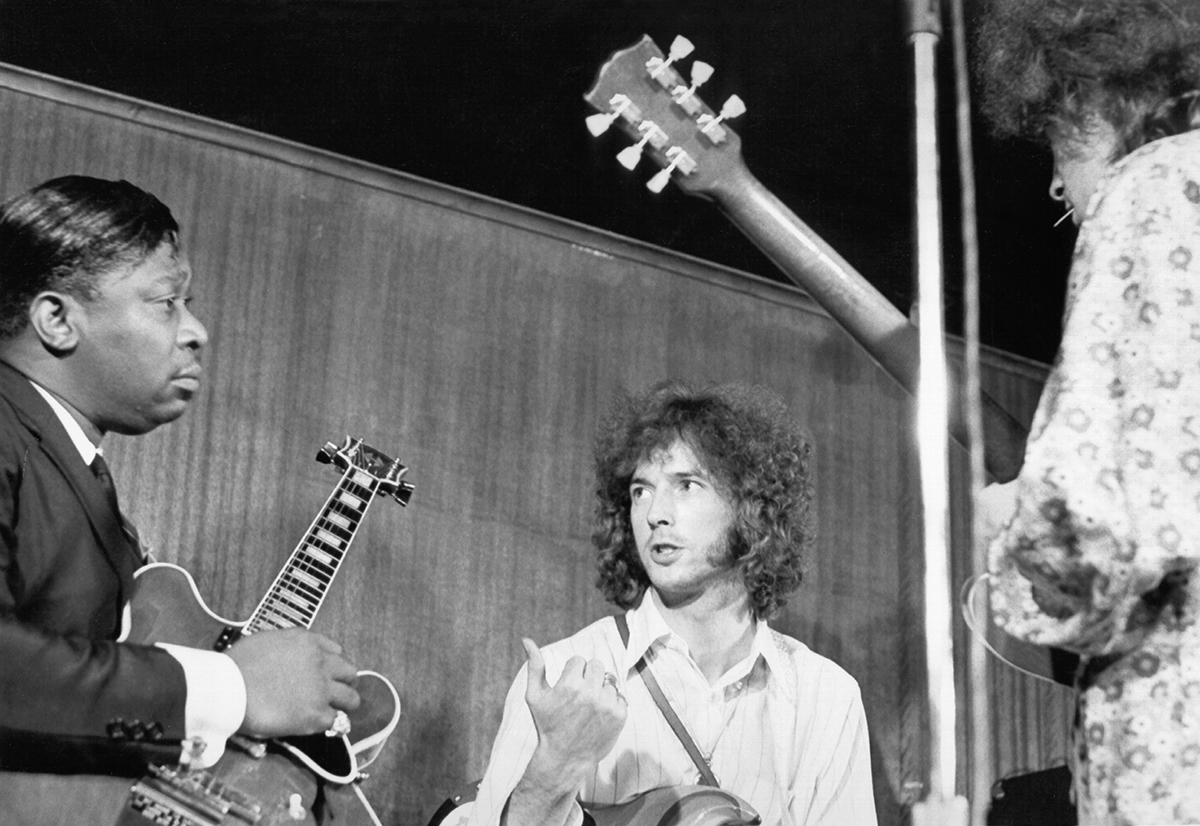

And while there are many great moments in an artist’s career that exist only in memory, we have photos of when B.B. King met Eric Clapton, and his rise to broader popularity began. It was the night he and Clapton famously jammed at New York City’s Cafe Au Go Go. The event is captured in a few prosaic snapshots that include guitarist Elvin Bishop. King is playing his Gibson ES-355 electric guitar, while Clapton — wearing his Cream-era bouffant hairstyle — strums the Fool, his psychedelic-finished Gibson SG.

“Ha, ha! And look at me — I'm wearing boots,” B.B. says, viewing the photos. “I haven't worn boots for years, but this was during the early rock and roll era, and boots were popular. And look at us — we're sitting on those Fenders.”

King confirms it was, to the best of his memory, the first time he and Clapton met. And while he can't recall if the jam happened during a show or after hours, he swears Jimi Hendrix and Al Kooper of Blood, Sweat & Tears were there as well. If his recollections are accurate, there may even be a recording of that night’s jam on a tape somewhere in the Hendrix estate.

“I remember Jimi recording what we played that night,” King says. “He was supposed to give us a tape, but he died before I got mine. When I die, if I can find Jimi, he's going to give me my tape!” B.B. laughs and slaps his knee. “Because that was a memorable occasion. It has been a lot of years of fun, man.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“F****d me up completely. I couldn’t make head or tail of it.” Eric Clapton on the one guitarist who blew him away onstage

“We were underdogs that still had to prove ourselves.” Aerosmith feared their label would drop them if 'Toys in the Attic' wasn’t a success. Fifty years on, Joe Perry discusses the riffs that saved them from oblivion