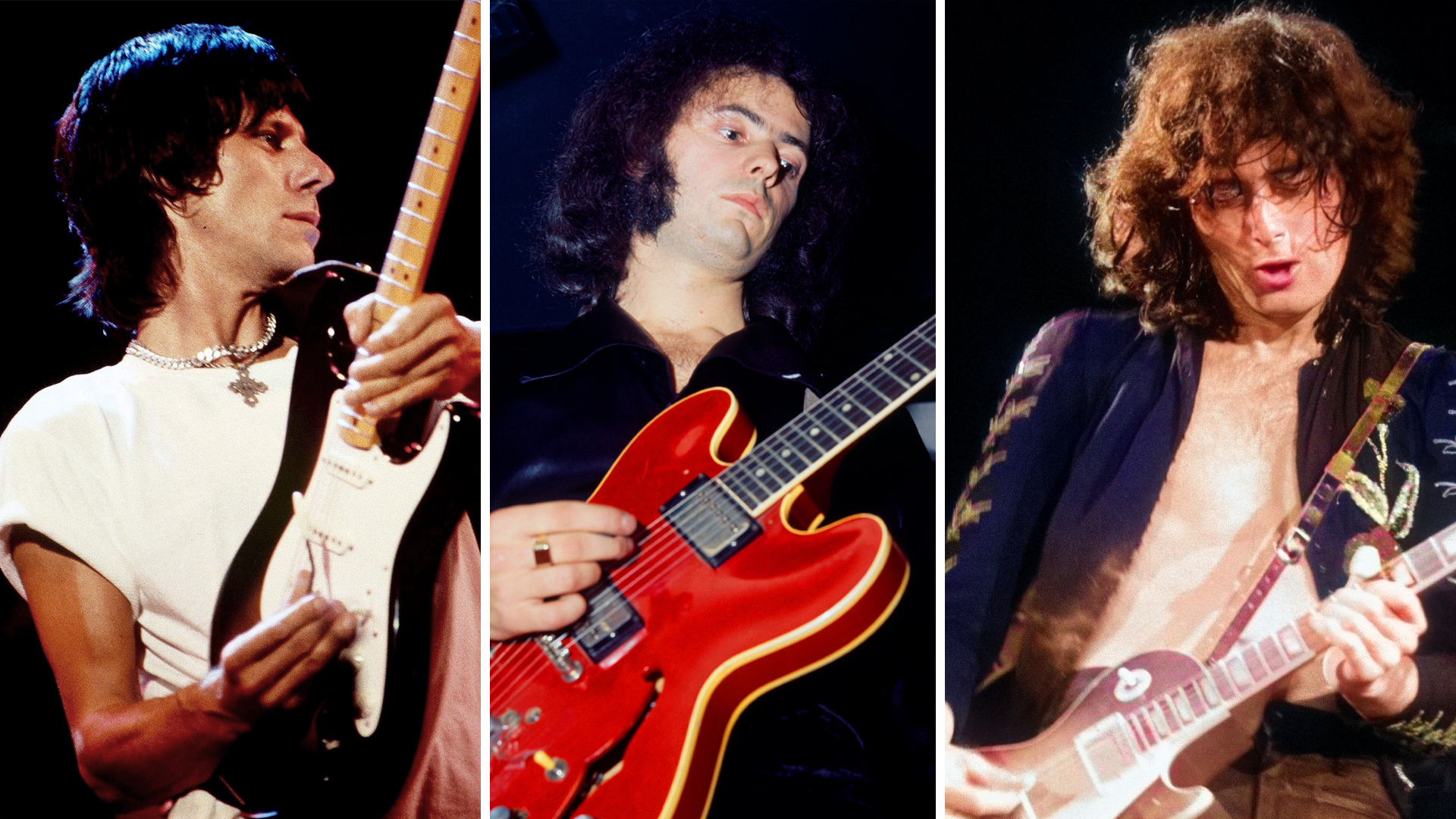

“We went from playing high school dances once or twice a month to playing six nights a week.” Alex Lifeson tells how one change helped Rush’s career take flight

Lifeson and his Rush bandmates were just 18 when a timely stroke of luck opened the door to Ontario's club scene

It takes a lot of hard work to make it in the music business, as well as plenty of luck.

But sometimes it just takes a little help from the government to get you on your way.

That’s what Rush bandmates Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee and drummer John Rutsey discovered in 1971, when the Ontario government lowered the drinking age from 21 to 18. The teenagers had been confined to playing high school dances, banned from the clubs due to their young age.

The change in drinking laws in 1971 changed all that.

“That was the year that we just turned 18,” Lifeson tells Q with Tom Power. “And we went from playing high school dances once, maybe twice a month if we were lucky, to playing six nights a week and some matinees on Saturdays, for week after week after week.”

“All those clubs popped up: the Abbey Road, Piccadilly Tube, Gas Works, Larry’s Hideaway. So you went from playing a week at one place to a week at another to another. You constantly played. And that’s really so important in the early stages, when you’re learning your stuff.”

But Rush weren’t just playing other band’s songs. They were writing their own originals and presenting them to the audiences.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We spent a lot of time writing music every chance we had,” Lifeson says. “We did all that stuff, and we were very dedicated to what we were doing.”

That commitment caused problems for Lifeson with his parents, who fought against his desire to pursue a career in music with his electric guitar rather than go to university. Their tense combat was revealed in a 1973 Canadian documentary Come On Children, which explored the generation gap between parents raised in more conservative times and their children, who were influenced by changes in norms brought about by the 1960s cultural revolution.

“I don’t see why I have to go through all the bullshit of high school to learn music,” the teenage Alex says to his parents at one point.

As Lifeson reveals today, he had a firm resolution to see what he could accomplish with his talents.

“I really had a belief in myself: If this music thing doesn’t work out, well then I’ll do something else,” he says. “I’ll work with my dad as a plumber’s assistant or whatever. But I really believed that this was going to work out. I never worried about it in the early days.”

Of course it did work out, and Rush enjoyed a long career with drummer Neil Peart taking over from Rutsey in 1974, although they had trouble early on finding their groove. As Lifeson has revealed, the success of 1975’s Fly by Night was followed by the disappointment of Caress of Steel.

"That record didn't do very well," Lifeson acknowledges. “People didn't respond to it.

"I remember playing Caress for Paul Stanley when we were touring with Kiss. We played it, and he had such a look on his face, like 'What the hell is this?' He started smiling and nodding, 'this is great guys...,' then nodding and quickly leaving.

"We were quite disappointed with that, because we thought we'd made something really, really special.”

Rush found their groove with the next album, 2112, and continued strong until the end. Lifeson and Geddy Lee still meet every week to jam.

In addition, Lifeson is enjoying success with his new group, Envy of None, which has just released its second album, Stygian Wavz. After feeling reluctant to call themselves a band with their first record, the group found their groove on Stygian Wavz.

“I bloomed on this record,” Lifeson says. “I let myself go a little more which is a good thing, 'cause I tend to hold back and be tentative with a lot of things. And on this record I just let go, and there was a new confidence and I had a better, clearer picture of what we wanted to create as a band."

Elizabeth Swann is a devoted follower of prog-folk and has reported on the scene from far-flung places around the globe for Prog, Wired and Popular Mechanics She treasures her collection of rare live Bert Jansch and John Renbourn reel-to-reel recordings and souvenir teaspoons collected from her travels through the Appalachians. When she’s not leaning over her Stella 12-string acoustic, she’s probably bent over her workbench with a soldering iron, modding some cheap synthesizer or effect pedal she pulled from a skip. Her favorite hobbies are making herbal wine and delivering sharp comebacks to men who ask if she’s the same Elizabeth Swann from Pirates of the Caribbean. (She is not.)