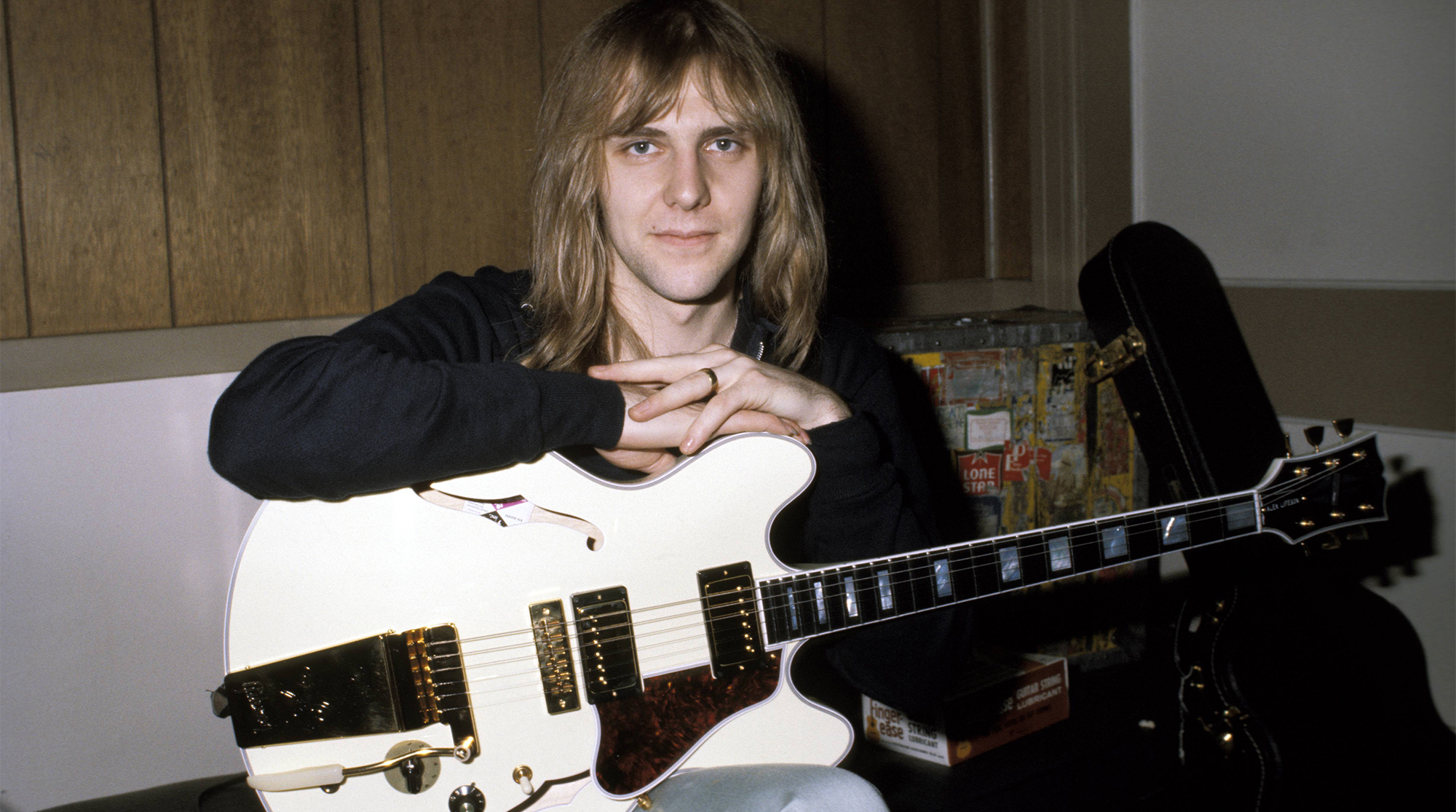

Watch Alvin Lee’s Mindblowing “I’m Going Home” Woodstock Performance and See His Fabled Gibson ES-335 Up Close

We take a look back at this game-changing concert and the mysterious guitar known as 'Big Red'.

Woodstock was already the stuff of legend when Michael Wadleigh’s documentary about the event arrived in theaters seven months after the 1969 three-day musical festival. As filmgoers thrilled to performances by the Who, Santana, Jefferson Airplane and a host of other acts, the guitarists in the audience eagerly awaited scenes of the festival’s headline act, Jimi Hendrix, and his explosive rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

But well before that footage passed through the projector, many of those viewers were blown away by the sight of guitarist Alvin Lee leading Ten Years After through a blistering performance of “I’m Going Home.”

The British blues-rock act was no stranger to American audiences, but neither was it well known. The group had supported Canned Heat on tour, and its third album, Stonehenged, released in early 1969 had reached 61 on the Billboard 200 chart.

Having expanded their signature boogie-rock with elements of jazz and psychedelic rock, Ten Years After were capturing fans on both sides of the Atlantic. Still, many viewers were unprepared for the sight of guitarist and frontman Alvin Lee ripping into his Gibson ES-335 with a flurry of lightning-fast blues guitar licks. At the time, Lee was one of the fastest players on Earth, earning him the nickname Captain Speedfingers, an epithet he refused to take too seriously.

“Basically, it just came from the excitement of playing live – the adrenaline,” he told the U.K.’s Guitarist magazine in a 1987 interview. “I used to hear tapes of the band from the mixing desk after a show, and sometimes I couldn’t believe it was me playing. I really didn’t know I could play like that. Ten Years After was all about excitement and energy. I basically played guitar from the hip – an instinct or reaction, if you like – because I’m not one for practicing. I’m a jammer. My attitude was to go for it, and on a good night, I could get it.”

Lee passed away in 2013, but his ES-335 remains as a testament to his aggressive style and knack for modifications. The instrument is still enshrined in its original flight case, bearing the name “Big Red” and an inscription in Lee’s own hand: “My famous 1958 Gibson 335 that I bought for £45 in Nottingham. Best investment I ever made – even had a fitted case.”

Although the guitar has been referred to as a 1959 model, it’s impossible to know the year of its make. The neck was replaced in the early 1970s after Lee broke the original at the Marquee in London, England, after accidentally ramming it into the club’s low ceiling. As a result, the serial number on the headstock has no bearing on the guitar’s year of manufacture. An orange label inside the 335’s upper f-hole bears the original serial identification, but it was obscured when the body’s interior was painted over in black, presumably to make the f-holes appear darker. Gibson’s original factory build number, which would have been visible through the lower bout’s f-hole, has been similarly obscured.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Complicating matters further, Lee extensively modded the guitar and added a single-coil pickup between the original PAFs. “I’m a keen dabbler,” he told Guitarist. “I’m always changing pickups and rewiring. The Gibson has the original 1958 PAF humbuckers with covers removed and a Fender pickup in the middle to give a bit more top. It’s good for the studio.” The Fender pickup has its own volume pot that Lee used like a blend control to add single-coil sheen to the humbuckers.

Further evidence of Lee’s dabbling is evident in the removal of the 335’s Bigsby, which he replaced in 1970 with a TP-6 tailpiece with fine tuners. The Bigsby either had a tuning issue that prompted the change or simply broke during one of Lee’s more frenetic onstage workouts.

But perhaps the guitar’s most distinguishing features are the stickers on its body, some of which have been in place since Woodstock. “They just got thrown on, actually,” Lee explained. “But when I broke the neck at the Marquee, I sent it back to Gibson for repair, and when it was returned they had lacquered over all the stickers. So they couldn’t come off.” The original neck had a fretboard with dot inlays; the replacement has block inlays. Its serial number indicates it was manufactured sometime between 1970 and 1972.

Despite trying various other electric guitars during his career, Lee clearly favored Big Red. “The 335 is still my main guitar,” he said. “I think it’s the size of the body. It fits me quite well. I love to play Strats, but I prefer to play them sitting down for some reason. I enjoy Les Pauls, but they feel too small and heavy. I’m just used to the 335.”

Today, the guitar is weathered from many years on the road and countless gigs. Lee placed the guitar in semi-retirement in 1986, when Tokai made him a replica. Big Red’s last gig has been recorded as having taken place in 1992. Lee stopped using it simply because it had become too valuable. Reportedly, he had been offered half a million for it.

There’s no doubt that Big Red’s most credible claim to fame is Ten Years After’s 11-minute sequence from the Woodstock movie. “When the movie of Woodstock came out, Ten Years After really took off,” Lee told Guitarist. “It was our spot on the movie that accelerated the band up to the 20,000-seater gigs instead of the usual 5,000-seaters.”

The group’s appearance may have catapulted them to fame beyond their collective imagination, but on the night in question, things didn’t go exactly to plan. Like other groups that performed, Ten Years After were flown in by helicopter to avoid the traffic jam leading to the festival. “There was a thunderstorm just before we were due to go onstage, so we had three hours to wait,” Lee explained. “I walked around the audience and around the lake, really got into it all – fantastic.”

At the time, Ten Years After were on their third American tour, criss-crossing the States. In July, they had played at the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival, sharing the bill with acts such as Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin, and the night before their appearance at Woodstock, they were in St. Louis, Missouri, with Nina Simone and Dizzy Gillespie. Recalls Ten Years After bassist Leo Lyons, “When we got to New York City and we were met by the guy that was looking after us in America, he said, ‘It’s a disaster. The roads are closed and the festival is, like, half a million people.’ So we drove as far as we could and then from there we took the helicopter.”

Ten Years After were originally scheduled to perform in the afternoon, but the infamous rainstorm delayed their performance until dusk. “The stage was flooded,” Lyons says. “There were cables running all the way across the stage, nothing like you get on a festival now with health and safety factors taken into account. In between the cables was water. Alvin said, ‘If one of us dies, we’re going to sell a hell of a lot of records!’ ”

Ten Years Afters’ hour-long set opened with “Spoonful” and was followed by three takes of “Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl.” “Because of the rain and the humidity, we had to keep stopping,” Lyons says, explaining the numerous attempts at the song.” Next was the drum solo “Hobbit,” performed to give Lee a moment to work on Big Red. Notes Lyons, “Alvin broke a string and we needed time to tune up.”

From there, the group performed “I Can’t Keep From Cryin’ Sometimes,” “Help Me” and finally “I’m Going Home,” which Lee famously introduced as, “I’m Going Home… by helicopter.” But as Lyons observes, “He was totally wrong, because after dark the helicopter stopped running.”

Although Ten Years After were music history at Woodstock, Lyons had little chance to savor the moment. “I spent most of the time in the back of U-Haul truck, hiding from the rain,” he says. “I intended to get something to eat, but just after I got to the festival, Pete Townshend came over to me and said, ‘Don’t eat anything or drink anything because there’s so much acid going around.’ So we were just sitting there waiting to go on, waiting for the rain to stop.”

Despite that, the significance of Woodstock is not lost on him. “It changed the music business forever,” Lyons says, “because, up until that point, you had your pop acts and then you had what were then called the ‘underground’ acts. There wasn’t much money to be made out of underground acts at the time, but once that whole thing happened, record companies jumped on it. Ten Years After went from playing to three to five thousand people to 20,000 regularly, and up to 50,000, 60,000 a night.”

Thanks to Leo Lyons, Suzanne Lee-Barnes and Loraine Burgon for their assistance with this article.

“We’d heard Jimi Hendrix, we'd heard the Who, but now we finally got to see these guys. And watching Jimi Hendrix burn his guitar….” Grace Slick on Hendrix at Monterey, Jefferson Airplane and the Spanish origins of “White Rabbit”

“I’m still playing but I’m covered in blood. Billy’s looking at me like, ‘Yeah! That’s punk rock!'” Steve Stevens on his all-time worst gig with Billy Idol — and the visit to Jimi Hendrix's grave that never happened