The Gear Behind the Beatles’ ‘Let It Be’

In the days before the release of the 'Get Back' documentary, we look back at the guitars and gear that defined the Fab Four's long, cold, lonely winter of 1969.

When director Peter Jackson unveiled the preview of his documentary series The Beatles: Get Back this past winter, fans were dazzled by the sight of the Fab Four’s smiling faces, and with good reason.

The film is a document of the group’s notoriously difficult Let It Be sessions, a tortuously bleak period in January 1969 when the British group nearly broke apart while attempting to return to the simpler style of music on which they founded their career.

Jackson’s sneak-preview footage turned the old story on its head, showing the Beatles laughing and clowning with one another in a style not seen since the heady days of Beatlemania. But it wasn’t just the Beatles’ smiling faces (or George Harrison and Ringo Starr’s snazzy threads) that caught the eyes of guitarists.

You didn’t need a particularly sharp eye to notice the thrilling sight of a few new sparkling silverface Fender amplifiers, a pair of large Fender Solid-State P.A. speaker columns, and George Harrison’s solid-rosewood Fender Telecaster – among the treats that stood out in the newly restored film footage.

No doubt many musicians will tune in to the six-hour special when it premieres this fall to see the gear as much as to view the previously unreleased Beatles footage.

The Beatles’ various eras are defined as much by musical styles as by clothing and hair fashions, and they are specified by musical equipment. Their history is full of consequential moments when new gear brought fresh sounds into the band’s music.

They include the 1964 arrival of George Harrison’s 1963 Rickenbacker 360/12 12-string in time for the album A Hard Day’s Night, Lennon and Harrison’s acquisition of Fender Stratocasters for Help!, and their subsequent purchase of Epiphone Casinos in 1966.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Sgt. Pepper’s saw McCartney give up his Hofner bass for a Rickenbacker 4001S, and the White Album brought a new electric guitar, Harrison’s “Lucy” Les Paul, into the fold.

Along the way there were other instruments, including the sitar, Mellotron, Hohner electric piano, and Moog synthesizer, that added new textures to their music. The Let It Be sessions would be the last time such a gear transformation took place, and its source was largely down to one company: Fender Musical Instruments.

The Twickenham Sessions

The January 1969 Let It Be sessions divide neatly into two groups: those held at Twickenham Film Studios, from January 2 through 14, and those that took place at the Beatles’ Apple Studios from January 21 through 31, including their final rooftop performance.

Starting out at Twickenham, Harrison largely played Lucy, the 1957 formerly goldtop Gibson Les Paul gifted to him by Eric Clapton in August 1968, as well as his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar. Lennon almost exclusively played his 1965 Epiphone Casino, which he’d had professionally sanded down to bare wood and covered with two coats of nitrocellulose in 1968.

As for McCartney, he had his 1961 Hofner violin bass as well as his newly stripped Rickenbacker 4001S bass, which he didn’t use. Also on hand was a Fender VI six-string bass of unknown vintage that Lennon played when McCartney switched from bass to piano for the songs “Let It Be” and “The Long and Winding Road.”

The new equipment for Lennon, Harrison, and McCartney at Twickenham consisted mainly of guitar amps. Lennon and Harrison each had new silverface 1968 Fender Twin Reverb amps, while McCartney used a new silverface 1968 Fender Bassman.

At Apple Studios

The misery of rehearsing on Twickenham’s vast, chilly soundstage in the middle of winter took its toll on the Beatles within days. After arguing first with McCartney and then Lennon, Harrison quit on January 10, returning on January 15 with the ultimatum that the group abandon Twickenham and return to Apple Studios.

It was at this point that the sessions became happier, not only because of the return to familiar territory but also because of keyboardist Billy Preston, whom Harrison had invited to sit in on the sessions.

Just as Clapton’s presence at Abbey Road Studios had helped make the group behave during the recording of the White Album’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” so did Preston’s keep the Beatles’ attitudes more positive.

Preston’s arrival also corresponded to the arrival of new gear from Fender in the United States. McCartney had been eager for the sound of a Fender Rhodes electric piano to appear on the album. Andy Babiuk relates how Ivor Arbiter, Fender’s U.K. agent, secured a pair of the pianos, which were rush delivered from the states.

With them came a new surprise for Harrison: a solid-rosewood Telecaster, custom made for him. Fender planned to add the model, as well as a solid-rosewood Stratocaster, to its lineup and believed a pair of high-profile guitarists could help publicize the new products.

While Harrison received the Telecaster prototype, the Stratocaster was intended for Jimi Hendrix, who died before it was delivered. In addition to Harrison’s new Telecaster, McCartney brought his 1963 Hofner bass to the Apple sessions, the 1961 model having been stolen shortly after the Twickenham sessions wrapped up. He also used his Martin D-28 – a right-handed model strung lefty – for “Two of Us.”

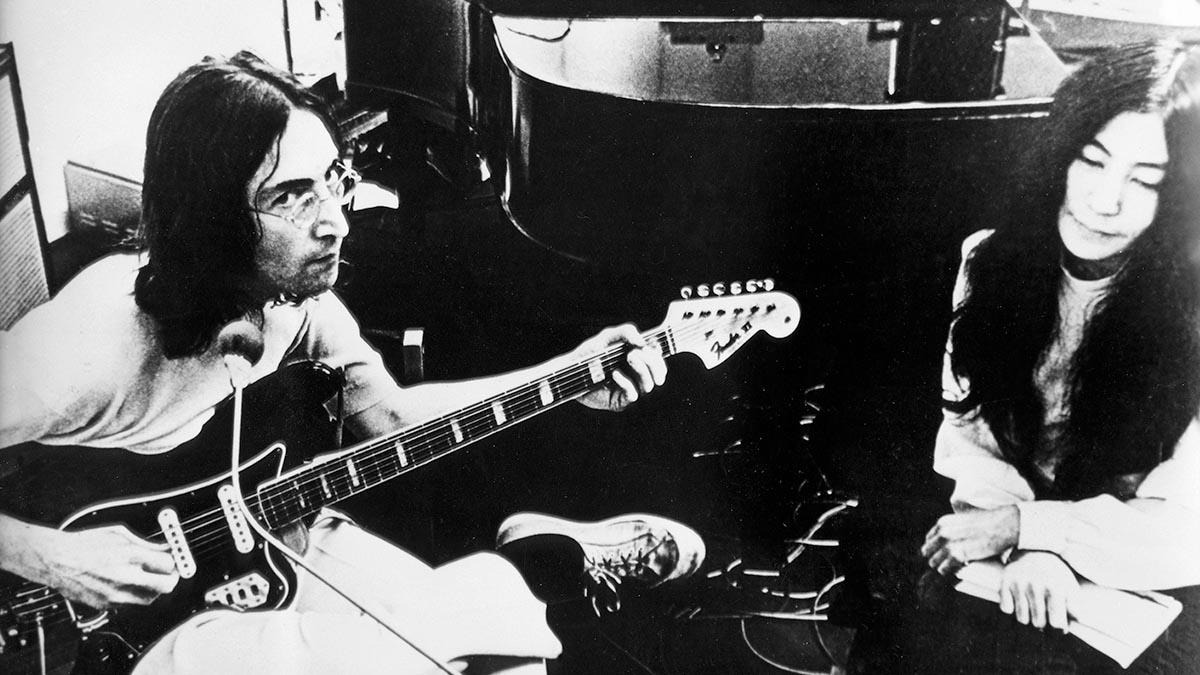

Lennon continued to use his Epiphone Casino, as well as Harrison’s stripped Gibson J-200 and his Martin D-28, whose finish he’d sanded off, just as he had on his Casino and Gibson J-160E. Finally, Lennon played a Hofner 5140 Hawaiian Standard electric lap-steel guitar on Harrison’s “For You Blue.”

Once again, the new silverface Fender Twin Reverb and Bassman amps were called into duty, as was a new Fender Solid-State series P.A. system, which the Beatles used to monitor vocals in the studio. In addition, Harrison used a blackface Deluxe Reverb, a transitional Fender Bassman, and a Leslie 145RV rotary-speaker cabinet.

The result of these gear changes is an album that sounds unlike anything else in the Beatles’ catalog. Over the next pages we dig into the guitars and other pieces of gear that defined this brief but consequential moment in the Beatles’ history and music.

1968 Rosewood Fender Telecaster

Brian Epstein had promised Jennings, Vox’s parent company, “as long as I am their manager, the Beatles will use Vox amplifiers.” When Epstein died in August 1967, his gentleman’s agreement was nullified, opening the door for Fender sales chief Don Randall to interest the group in his company’s wares.

“Paul was outgoing and enthusiastic, a great guy to talk to, very upbeat,” said Randall, who recalled speaking with McCartney about “pickups, styles, and everything.“ That meeting led to Fender supplying the Beatles with a lefty Jazz Bass, a VI six-string bass, and various amps during the White Album sessions.

Undoubtedly, the most intriguing guitar to come from this association was the prototype Rosewood Telecaster custom-made for Harrison and delivered during the Let It Be sessions.

The guitar was created under master builder Roger Rossmeisl, who had previously worked for Rickenbacker, where he designed the 325 and 360/12 models played by Lennon and Harrison, respectively.

The Rosewood Tele’s body had a thin piece of maple sandwiched between a solid rosewood top and back, over which a clear polyurethane was applied, sanded, and hand rubbed with a fine cloth to achieve a satin finish. The Telecaster was flown to England in its own seat and delivered to Apple in December 1968.

Harrison used it for much of his work on Let It Be, including the rooftop performance. Later in 1969, he gave the guitar to Delaney Bramlett, of Delaney & Bonnie, from whom he learned slide guitar technique. Bramlett sold the guitar in 2003, where it fetched $434,750 when it was purchased by an intermediary for Harrison’s widow, Olivia.

1957 Lucy Gibson Les Paul (serial number 7-8789)

One of the most storied guitars in Harrison’s collection, this former goldtop 1957 Les Paul was a gift from Eric Clapton, who gave it to Harrison in August 1968 during the White Album sessions.

Harrison had just recommitted to playing guitar, following a year’s worth of sitar studies with Ravi Shankar. Previously, John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful had owned the guitar before trading it to Rick Derringer – then with the McCoys, who were touring with the Spoonful – in exchange for an amp.

“It was a very, very used guitar, even when I got it,” Derringer said of the Les Paul, “so I figured that since we didn’t live far from Gibson’s factory in Kalamazoo, the next time the group went there I’d give it to Gibson and have it refinished. I had it done at the factory in the SG-style clear red finish that was popular at the time.”

Derringer eventually sold it to Dan Armstrong’s Guitar Service on 48th Street in New York City, which is where Clapton purchased it. The guitar saw heavy use from that point on.

Clapton wielded it for his solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” and Harrison played it on the White Album, for his solo on Abbey Road’s “The End,” and during the Let It Be Twickenham sessions. Stolen in 1973, Lucy was eventually retrieved, and Harrison owned it until his death in 2001.

Arbiter Fuzz Face

The Beatles had been fans of distortion since the making of their second album, With the Beatles, in 1963.

They experimented with a Maestro Fuzz-Tone during the recording of “She Loves You” and “Don’t Bother Me,” and in 1965 McCartney ran his bass through a Tone Bender for the recording of “Think for Yourself.” It’s not known when the Arbiter Fuzz Face entered the Beatles’ world, but Harrison is seen using one in photos from the Twickenham sessions.

1965 Epiphone Casino

Early in 1965, Lennon played some new Beatles recordings to a reporter from Melody Maker magazine. “Hey, listen! Hear that playing by Paul?”

It was probably during playback of “Ticket to Ride” or “Another Girl.”

“Paul’s been doing quite a bit of lead guitar work this week,” Lennon explained. “I reckon he’s moving in.”

Not content with his bass work, McCartney, who’d started in the Beatles as a guitarist, bought himself an Epiphone Casino in 1964 and had it restrung to accommodate his lefthanded style. In 1966, Lennon and Harrison bought 1965 Casinos and used them on the sessions for Revolver, as did McCartney.

McCartney's ’62 model had the black knobs and Gibson-style headstock of the period, while Lennon and Harrison's ’65 models had gold knobs and the later flared Epi head. Harrison's came with a Bigsby, Lennon's with the regular trapeze tailpiece. Lennon and Harrison had the guitars sanded down to the bare wood in 1968.

“I think that works on a lot of guitars,” Harrison said. “If you take the paint and varnish off and get the bare wood, it seems to sort of breathe.” McCartney still owns his 1962 Casino, Olivia Harrison owns Harrison’s ’65, and Yoko Ono owns Lennon’s ’65.

1960s Hofner 5140 Hawaiian Standard Lap Steel

It’s unclear where it came from, but a Hofner Hawaiian Standard lap steel was among the instruments at Apple Studios on January 25, when the Beatles cut Harrison’s “For You Blue.”

The German-made Hofner brand was distributed in the U.K. by Selmer. According to Hofner’s 1964 catalog, the 5140 lap steel featured a solid-wood body with a “lustre mirror finish, shaded sunburst to rich brown,” and was fitted with a double-pole single-coil Nova-Sonic pickup with tone and volume controls.

Lennon plays the lap steel on “For You Blue” using what some have identified as an early disposable butane lighter as a steel.

Gibson SJ-200

Harrison bought his Gibson J-200 on a trip to the U.S., presumably in 1968, as that was when it first appeared on a Beatles session. The guitar had a traditional sunburst finish, a gold-plated Tune-o-matic bridge, and Grover tuners.

Harrison had the guitar in the studio during the Let It Be sessions, where Lennon frequently played it, rather than his own Gibson J-160E or stripped Martin D-28. This appears to be the guitar Lennon is using to perform “Two of Us” in the original Let It Be film.

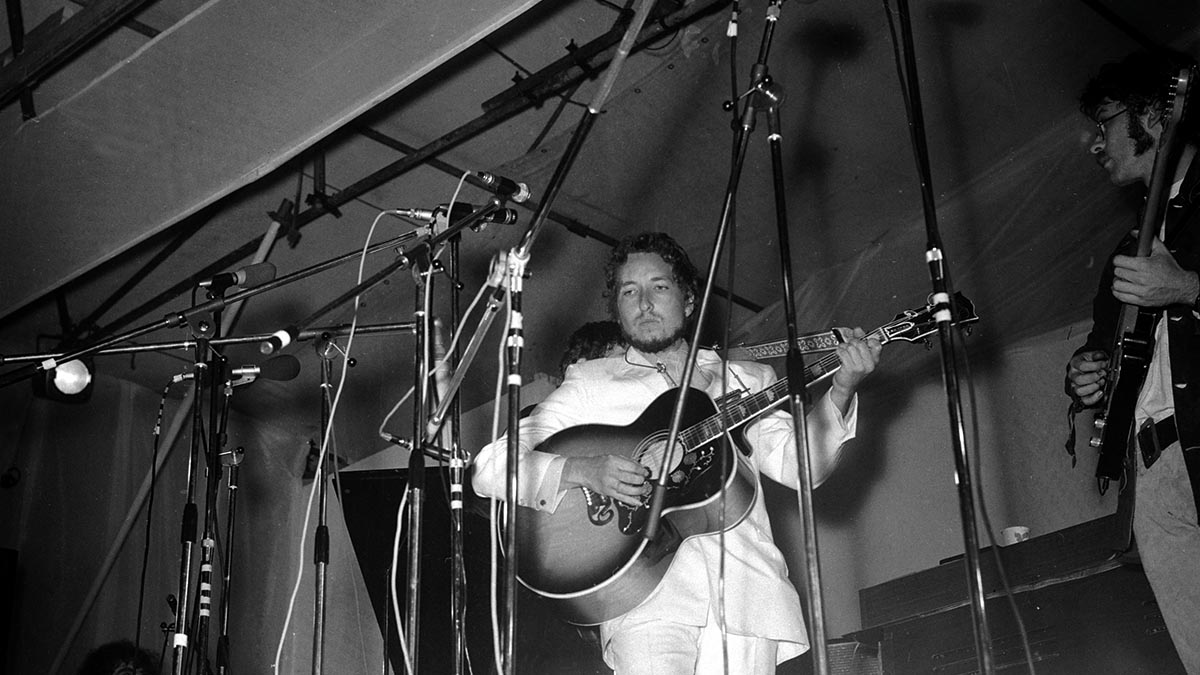

The guitar is seen only from the side, but the woods and finish rule out the J-160E and the D-28. Harrison gave the J-200 to Bob Dylan, who played it at the Isle of Wight Festival in August 1969, a show attended by Lennon, Harrison, and Ringo Starr, and it’s the guitar he’s holding on the cover of Nashville Skyline.

1963 Hofner 500/1 violin Bass

Stu Sutcliffe was the Beatles’ first bass player and used a ’59 Hofner 500/5. With his departure in 1961, McCartney took over bass duties and in 1961 bought his first bass, a left-handed Hofner 500/1, in Hamburg for £30.

“I got my violin bass at the Steinway shop in the town center,” he recalled in 1993. “I remember going along and there was this bass which was quite cheap. My dad had always hammered into us never to get into debt because we weren’t that rich.”

The ’61 Hofner saw him through the band’s early days, but in 1963 he bought a lefty ’63 500/1, which he used onstage and in the studio throughout the Beatles’ glory years. The pickups provide the main visual clues to tell the two Hofners apart: The pickups on the ’61 bass are close together at the neck, while the ’63 bass has them spaced conventionally, at the neck and bridge.

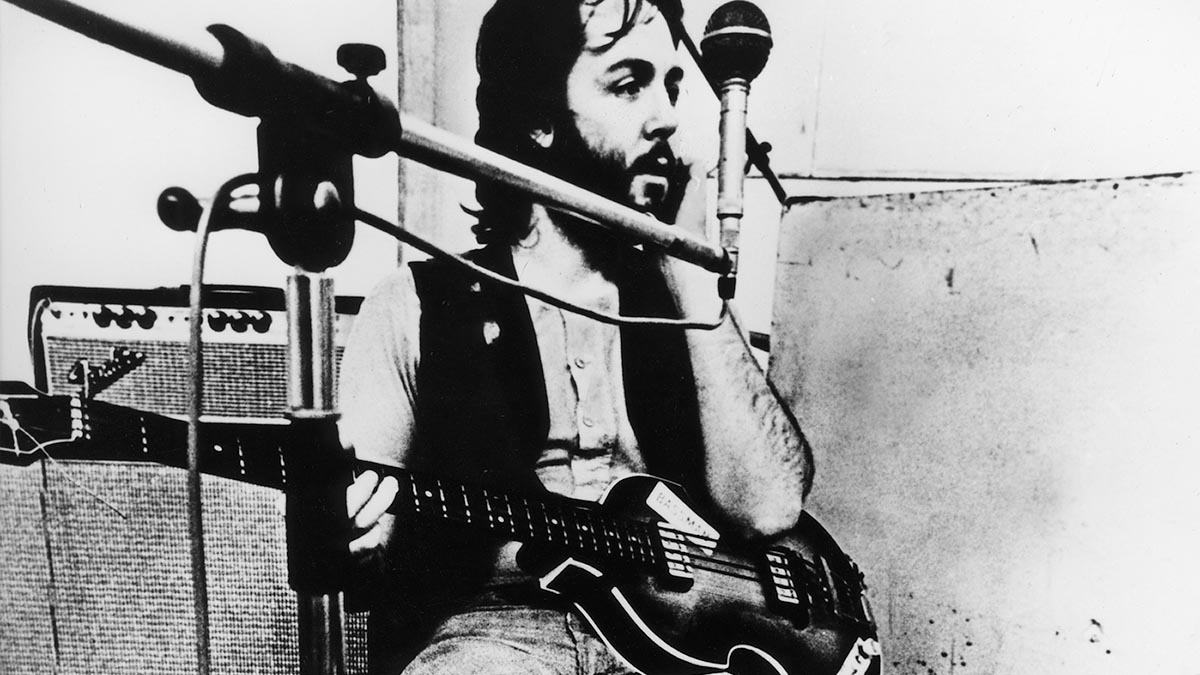

In the roots-rock spirit of the Let It Be sessions, Paul returned to his Hofner 500/1, using his ’61 model at Twickenham and reverting to his ’63 model when the other was stolen sometime after filming wrapped at the studio.

“I noticed a clip of me in the Let It Be rooftop sequence, and, you know, you play differently when the instrument itself isn’t heavy,” he said. “You’re tempted to play more melodic riffs and more kind of ‘guitar’ parts, really. I think its tone, for a little lightweight bass, is incredible, because it really sounds like a string bass sometimes.”

Although he retired the 500/1 after the Beatles broke up, McCartney began using it again at the recommendation of Elvis Costello when the two collaborated in the 1980s on McCartney’s Flowers in the Dirt and Costello’s Spike. He still owns the bass.

1960s Fender VI bass

Introduced in 1961, the Fender VI six-string bass was designed with guitar players in mind. Its offset body was similar to that of the Jazzmaster/Jaguar, it was tuned an octave below a standard guitar, and it had a 30-inch scale length, the same as a short-scale bass.

The Beatles received one in 1968, when Fender began supplying the group with gear, and both Lennon and Harrison played it on the White Album. The VI found use on the Let It Be sessions whenever McCartney was needed for piano duties. The Beatles originally intended to record live, with no overdubbing.

Although they later abandoned that approach, they adhered to it through the January sessions, with the result that Lennon found himself playing the VI for both “Let It Be” and “The Long and Winding Road.” He can also be seen in the Let It Be film playing the instrument on “Dig It,” where he frets full chords.

Either due to his unfamiliarity with the instrument or his lack of interest in the song, Lennon made a mess of his VI bass work on “Let It Be,” prompting McCartney to replace it at the behest of producer George Martin. Lennon’s bass playing on “The Long and Winding Road” was deemed sufficient.

1968 Fender Twin Reverb

In 1968, Fender ushered in the silverface era for its amplifier line with a new brushed aluminum faceplate in place of the original black plate, and a silver grille cloth with subtle turquoise stripes, framed by aluminum trim.

The amp had two 12-inch speakers, a vibrato circuit, and spring reverb, and produced a total of 85 watts from four 6L6 power tubes. Lennon and Harrison received a pair of new silverface Fender Twin Reverbs during the Let It Be sessions.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.