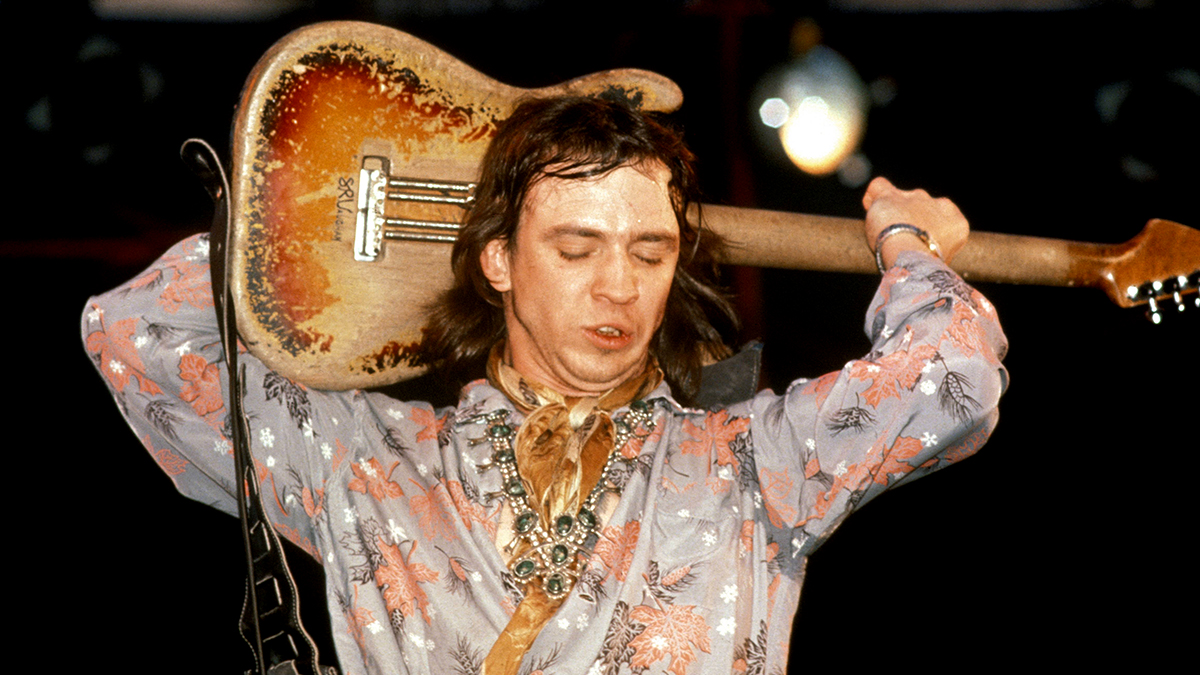

“Stevie had this superstition about numbers.” Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar and amp secrets are revealed in this deep dive into his gear and tone

César Díaz shared the several notable improvements he made to SRV's gear with Guitar Player in this classic interview

An outspoken advocate of tube amps and vintage guitars, the late César Dîaz worked as an amp tech and gear adviser to Stevie Ray Vaughan, Eric Clapton and Keith Richards, among others electric guitar players. He was working with Bob Dylan when Guitar Player caught up with him for a discussion about guitarists’ gear and tone.

Among the players Dîaz spoke of, Stevie Ray Vaughan stood out as one who benefited perhaps most significantly from the tech's insights. Given that SRV was young and working with little guidance at the time Dîaz met him in 1979, he stood to get more from him than more experienced players. Stevie — whom fellow Austin guitarist Eric Johnson recently lauded for his uncelebrated singing talents — benefited with improvements to his guitars and, especially his amps.

What was the state of Stevie Ray Vaughan's gear when you started working with him?

I first saw Stevie in 1979 at a club in Bethesda, Maryland, and I immediately got floored. I went, "Man, the guy can play his ass off, but he sounds like shit!"

So I went up to him and said, "Look, you sound great, but I can make you sound better." He had the '59 Strat he called Number One, except that it wasn't beat-up yet and the letters "SRV" were still intact. He didn't have the left-handed whammy bar on it. So when I told him that Hendrix had his bar on the top so that he could do that vibrato stuff with his elbow, Stevie said, "Oh, great, can you get me one of those things?" I did, and I thought that he would put it on a new Strat body or something like that, but the next time I saw him he had it on Number One.

You know, Stevie wasn't an educated guy. He just did what came natural to him. It was up to somebody else to make him sound great. He just plugged in and played. Later on, though, he did become somewhat of a maniac and really cared about his stuff.

What was his amp in the early days?

He was using a black-panel Vibroverb, the rare one with the single 15-inch speaker. This is not to be confused with the chocolate-brown one that has an active tone section. When he added a second Vibroverb, the two were in numerical sequence with their serial numbers. They were 1964s, the only year of production for this particular model. In '65 they became the Pro-Verb. Stevie was sounding fine with that pair of 'Verbs, but the stuff was a little loose on the low end.

Was he open to suggestions about how to improve his sound?

Always. When we were on the road, he would come in my room in the middle of the night to talk about how to sound better. He was always happy to have me around because I could make the changes in the equipment. He could get uptight about his sound, and around the crew I got to be known as Stevie's pacifier.

What was Vaughan's first major equipment change?

The first big change was replacing the amps' output transformers, because the old ones were worn out. The secondary taps on the transformers were not matching, and with push/pull amp designs it's very important that the two taps read close to each other. If not, to put it in simple terms, one tube will not be heating up or phasing with the other as well as it could. One of the first things I do to an amp is test the DC resistance, and then I test the signal out of the transformer taps to see how each tube is being pulled.

Did his use of beefy strings—.013 through .052—and half-step-low tuning affect his amp performance?

Definitely. An amp's input sensitivity is set for a certain amount of pitch. Stevie's nonstandard frequencies created a different set of spikes in the amp, so his input had to be buffered slightly to reduce the signal from the guitar. He also hit the low strings real hard, which would do wonderful things to the tubes [laughs], like sparks and Fourth of July kinds of things. I saw plenty of smoke coming out of his amps. In some of his passages he would be hitting spikes that would go up to 700 plate volts! But he felt that it was his sound, and that the Vibroverb was the amp for him.

See, Stevie had this superstition about numbers. He was used to his controls being set at a certain level, no matter what the amp was sounding like at that point. So in order to avoid problems, I would back off the volume control by unscrewing the knob and turning it back a bit so it would appear to be at the same level as before. Or I'd turn it ahead a bit, depending on how the amplifier was working at that particular time. That way when he would turn the volume to 6, it would sound the same to him.

Do you mean that no matter where he was playing, he always dialed the same settings?

Yes, the same. Volume at 6, treble at 5 1/2, bass at 4. But he was up and down a lot with the guitar controls.

Were his guitars modified?

They were stock except for one that had an extra coil inside to cancel out the hum. I did try to tell him about the ways I had been rewinding pickups with reverse wrap and reverse polarity, but I wasn't the guitar tech. Rene Martinez was.

Did Stevie ever talk about the tone of other guitarists?

Oh, yeah. We were always talking about other players like Mike Bloomfield and Hubert Sumlin, Howlin' Wolf's lead guitarist. Stevie was also really into Otis Rush's tone. And Pee Wee Crayton and Guitar Slim as well. Most of those guitarists favored a bright, cutting tone similar to a Tele's.

Did you ever see Stevie play one?

The only time was during the In Step session for "The House Is Rockin'," when he used Paul Burlison's Esquire. Someone had added a rhythm pickup near the neck, so I suppose that qualifies it as a Tele.

Did Stevie play loud in the studio?

Yeah, as loud as he played anywhere. He never let an engineer or producer tell him to use little amps. When we started the In Step rehearsals in New York, Stevie was being extra particular about everything, to the point where it kind of got on the nerves of some of the other participants. He had a tough time making up his mind about things, so we took 32 amplifiers with us.

So he would hit these notes, and the whole place would rattle. There were 32 amps running into the board, and Stevie would put his headphones down in the middle of recording and come over to me and say, "The little Gibson amp upstairs is fucking up!" I'd give him a look like, "What, are you kidding me?" But then I would go check and sure enough, there was a problem with the amp. Stevie could really hear every little thing. It was amazing.

Had he found his ultimate sound?

No, not at all. He was always searching, looking, trying to learn more. And there was so much more that he wanted to do. He was never satisfied with his accomplishments, and being free from drugs allowed him to have an incredibly sharp focus on his future.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"The only thing missing is the noise from the tape loop." We review the Strymon EC-1 Single Head dTape Echo, a convincing take on a very special vintage tube Echoplex

A gigantic $360 off Positive Grid's celebrated BIAS amp sim software may have just put the nail in the coffin of my beloved valve combo