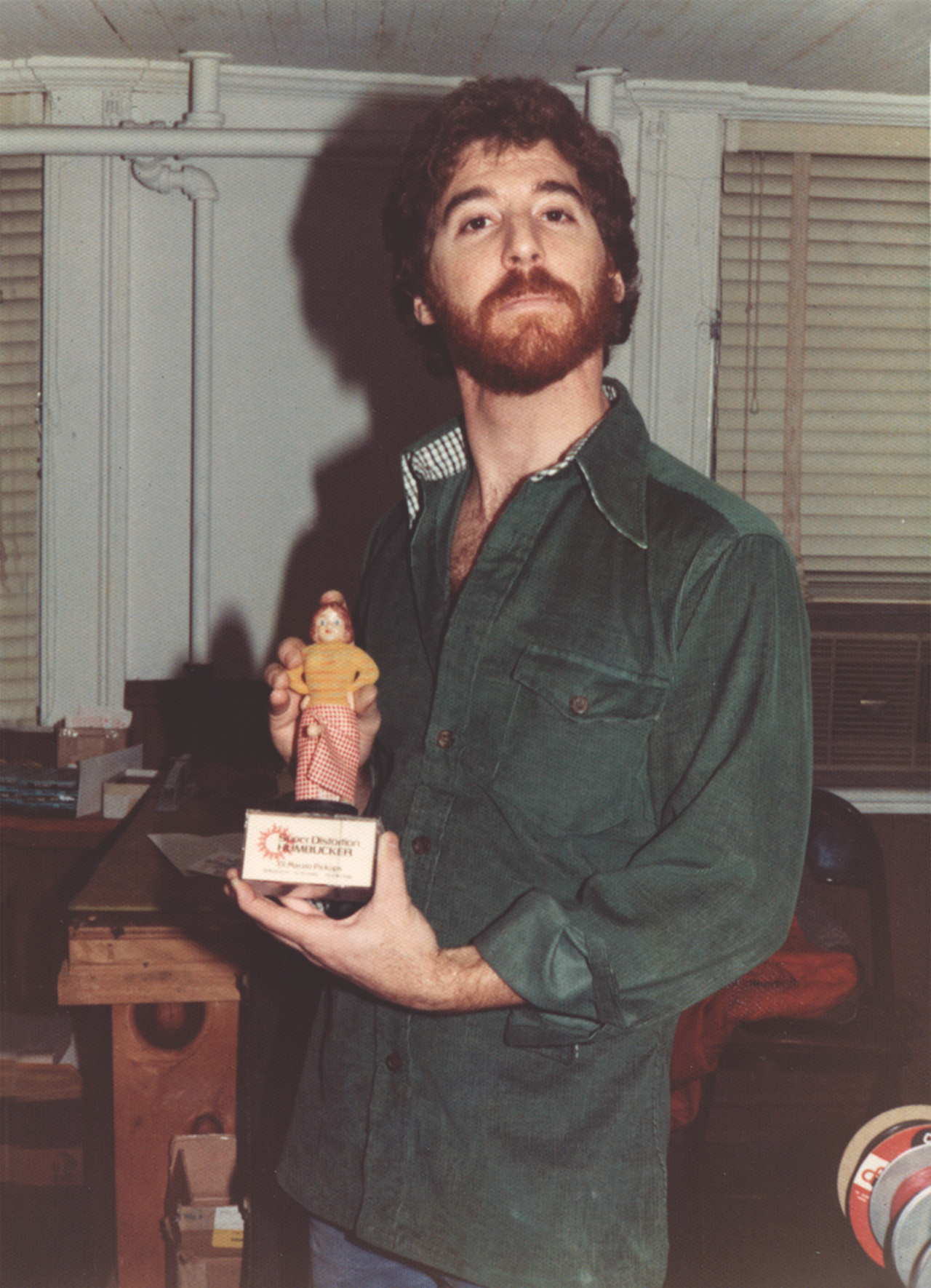

“I dreamt up the Super Distortion because I wanted to improve my guitar without chiseling a hole in the body!” On its 50th anniversary, guitarist and inventor Larry DiMarzio remembers how his company changed electric guitars forever

A massive hit with everyone from Kiss to The Grateful Dead, Larry DiMarzio’s pickup was the start of something big

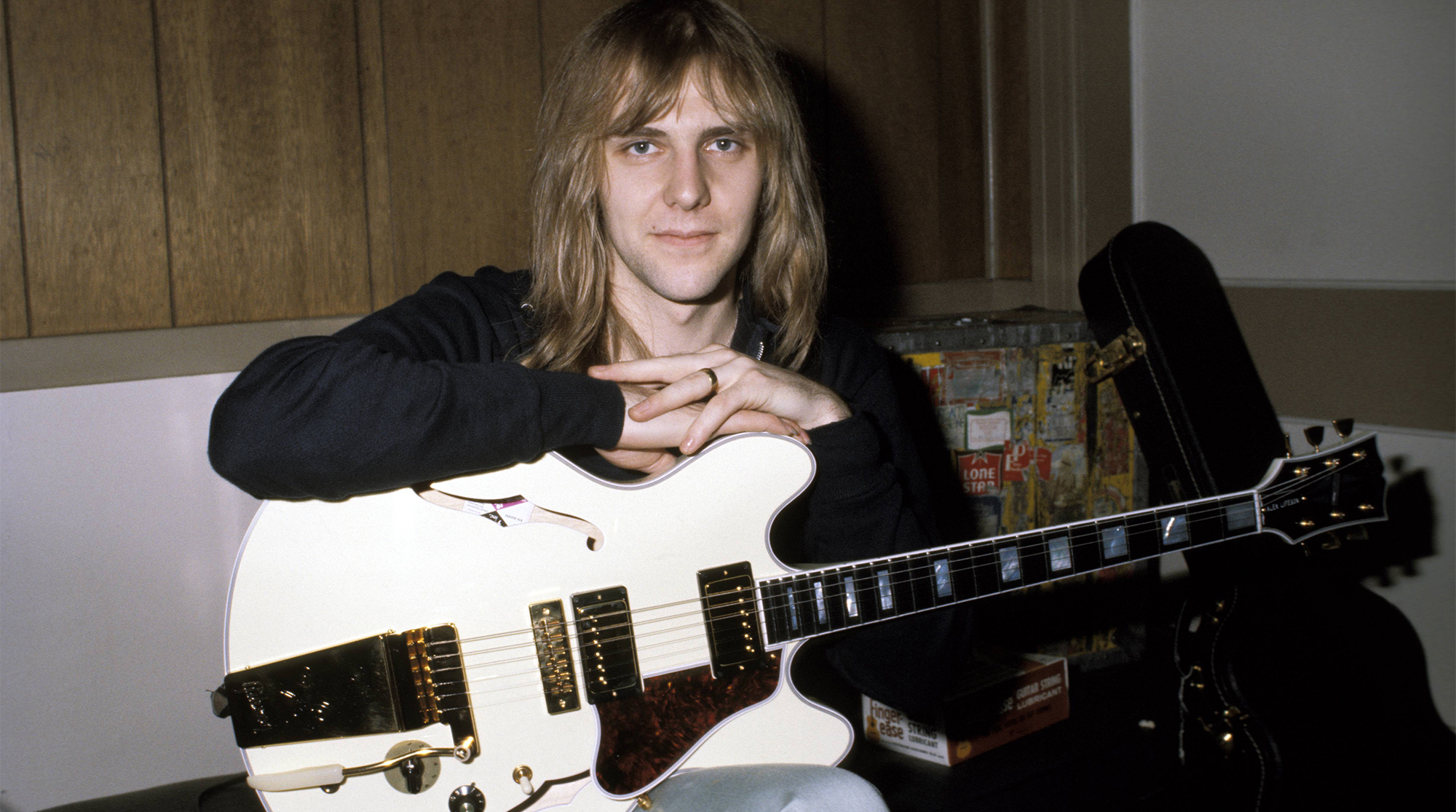

Innovator, guitarist, inventor and photographer are some of the words that define Larry DiMarzio, whose early interest in making guitars sound and play better led him to start a company that offered players better tone in the form of replacement pickups.

The concept was unheard of in the early 1970s, but DiMarzio revolutionized the music industry by doing what guitar companies couldn’t do — build drop-in pickups that replaced the stock units without modification to the instrument.

It was something he was adamant about because of his love for vintage guitars and his belief that owners should always be able to return them to stock if they desired. As he has said, “The Super Distortion humbucking pickup came about because I wanted to improve my guitar’s sound and output without chiseling a hole in the body and devaluing it.”

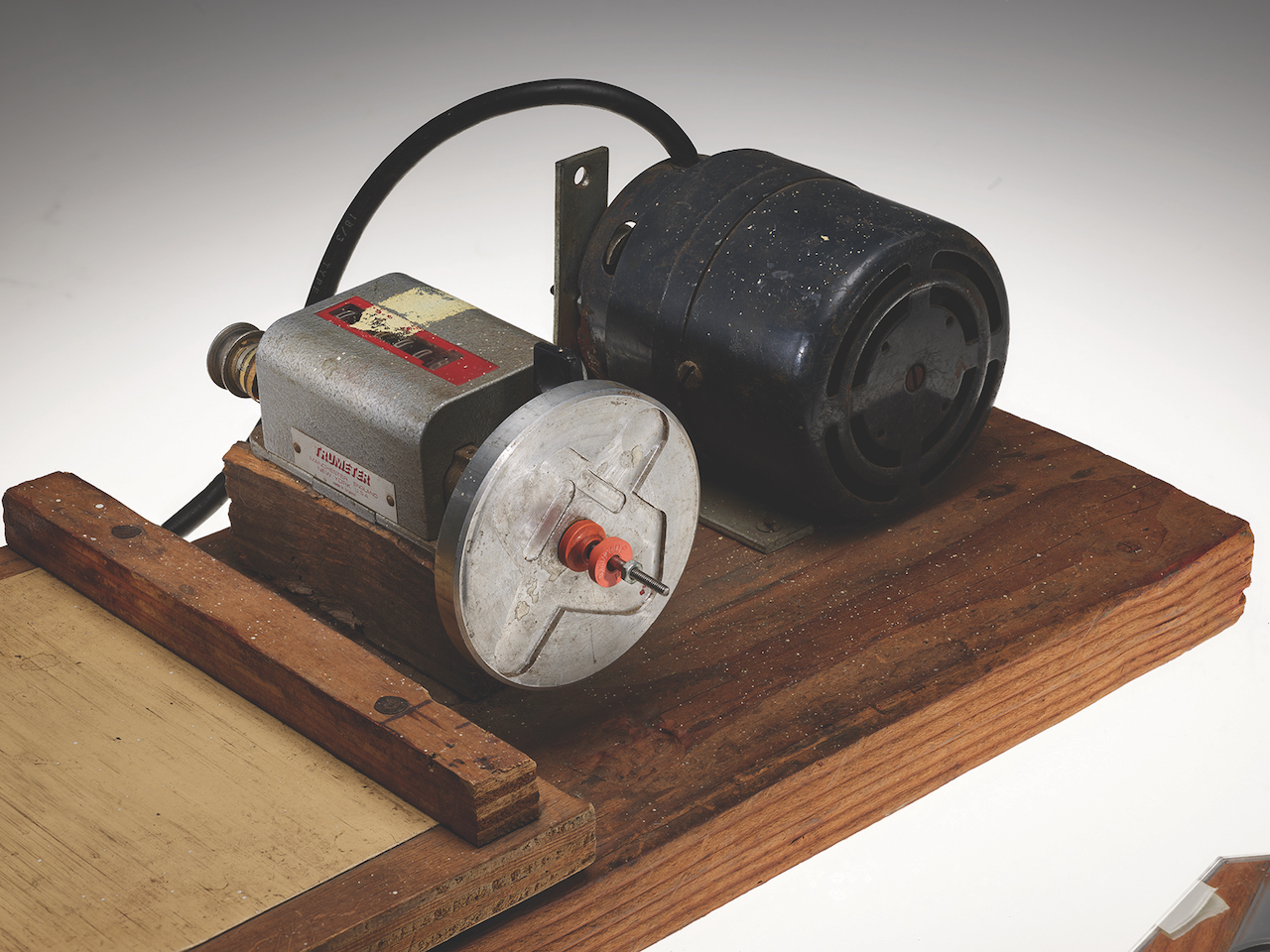

DiMarzio got his start in the M.I. business working at the Guitar Lab, near 48th Street’s Music Row, in New York City. It was there that he did repairs and fret jobs, installed Gibson humbuckers in Strats and Teles, and taught himself how to fix broken pickups, wind coils and tune them for a louder, warmer and fuller sound that would blend well with a distorted amplifier.

After much experimenting, he created the Fat Strat, later renamed the FS-1, which was a hit with Yngwie Malmsteen and favored by both David Gilmour and The Edge.

Next, DiMarzio set his sights on building a humbucker that would be tuned for the tone he wanted, and have a higher output to coax more sustain from an amp. He called his new pickup the Super Distortion.

It was soon adopted by Ace Frehley, Earl Slick and Al Di Meola, creating a ripple effect that led the Super Distortion to be used by artists such as Rick Derringer, Roy Buchanan, Jerry Garcia, Wishbone Ash, Rick Nielsen, Aerosmith, Ronnie Montrose, Iron Maiden, Allan Holdsworth and many others.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Along with other pickups DiMarzio was offering by 1974 — the Dual Sound, Fat Strat and Pre BS Tele — the Super Distortion was soon in demand by guitar makers.

“We were selling them to Wayne Charvel and they were going into a lot of guitars,” DiMarzio says. “Then we got picked up by Hamer, Dean and B.C. Rich. Think about this: None of those companies could really build anything, because who are they going to buy pickups from? They all started out with Super Distortions.

"Then Paul Hamer came to me and said, ‘Can you make a PAF for the neck position?’ I said, sure, we can make something like a PAF.’ But again, my attitude is always, What do I do to make it better?”

My background is electronics, but all I ever cared about was whatever it took to make things better

You were innovating on so many levels, starting out as a musician and improving your own gear. It set the stage for what followed with DiMarzio pickups, right?

Yeah, exactly. If you look at what I was doing, in many ways we were all doing and thinking about the same thing. I just started earlier than a lot of people, and pickups were the direction I wanted to go in.

But of course, I designed bodies, I designed necks and guitar bridges and tuning pegs, as well as all the electronic aspects. It was really about the major manufacturers ignoring us — the guys that were really playing.

So you felt that guitar manufacturers had basically forgotten what was good about vintage instruments?

I worked on a number of old Strats, Teles, 335s… The list goes on, and there was no way that what the major manufacturers were turning out, especially in the early ’70s, was really the same thing. They looked like the guitars, but they just didn’t do what they were supposed to do. Part of my revolution was, “I’m in complete, total hippie rebellion. I’m throwing all of that away, and I’m designing what I want from the ground up.”

The first truly successful product was, of course, the Super Distortion humbucking pickup, and it paved the way to introduce a lot of other things. It wasn’t really based on a Gibson Les Paul PAF humbucker. It went someplace completely different, like, “What am I going to put in a 1971 Les Paul that makes it sound like Eric Clapton or Leslie West?”

I was going from their records and/or live performances and taking that up a notch. My background is electronics and going to school for electronics, but all I cared about was whatever it took to make things better.

Your first powerful pickup was the Fat Strat, which led to the Super Distortion humbucker. You modified your Strat’s electronics, too, so it wasn’t just about getting more from a pickup.

It was a matter of how was I going to go out with one guitar and be able to cover, in a Top 40 band, all of the sounds that I heard on the pop records? It was like the equivalent of having a pedalboard built into the guitar.

You mentioned voicing the Super Distortion pickup to have that sound you were looking for — Leslie West and Eric Clapton. You can’t just slap a bunch of winds on a pickup and make it happen. So how did you do it?

Loads and loads of trial and error. Oddly enough, sitting right here is the amp, the original Fender Deluxe I used. I’d go to a show and here’s Neil Young playing out of an old Fender amplifier with Crazy Horse, with a sneaker hanging off the headstock of his Gretsch. And he got a great sound. So it was really a matter of going back to, How do I get more of that sound in a small club environment and not piss the bartenders off by playing too loud?

There were no pedals involved either. You were just going guitar into amp. Everything was straight guitar-into-the-amp.

Eventually, of course, a wah-wah pedal. But even with the wah pedal, I built a dual switch into it so you got a straight wire-bypass, because when you went into the wah, you always had a reduced level. Same thing with my other piece of stage gear at the time, the Maestro phase shifter.

You had to go straight wire-bypass so that when you came out of the device, you could turn the guitar up and get the amp to break up in a nice way.

Getting back to voicing, later on, of course, I met Leslie West and spent some time with him. Leslie had his own sound in his head. A lot of people go on about the Les Paul Junior, which by the way, I always adored. But it’s not just the Les Paul Junior and one pickup. It’s important that there’s no pickup in the neck position, because the magnetic field is interacting to some degree.

I started taking everything apart and going through lots of trial and error, because we had a lot of guitars coming through the Guitar Lab and a lot of bands were coming through there.

I have to stay current. The goal is not to turn into a dinosaur

One of the early bands that we worked with was Wishbone Ash, and they began coming to me to get Super Distortions put in their guitars. Al Di Meola did too. But the Super Distortion was already designed by that point, because, once again, I knew that I could plug it into a Fender amp, turn it up and get it to break up the way I wanted it to break up.

It was really simple and just a matter of volume control. If you wanted to clean it up, just roll it back a bit. Then, when you wanted that extra step, open it up and there you go.

Guitar players picked up on the Super Distortion right away, but did you still have to convince stores to carry them?

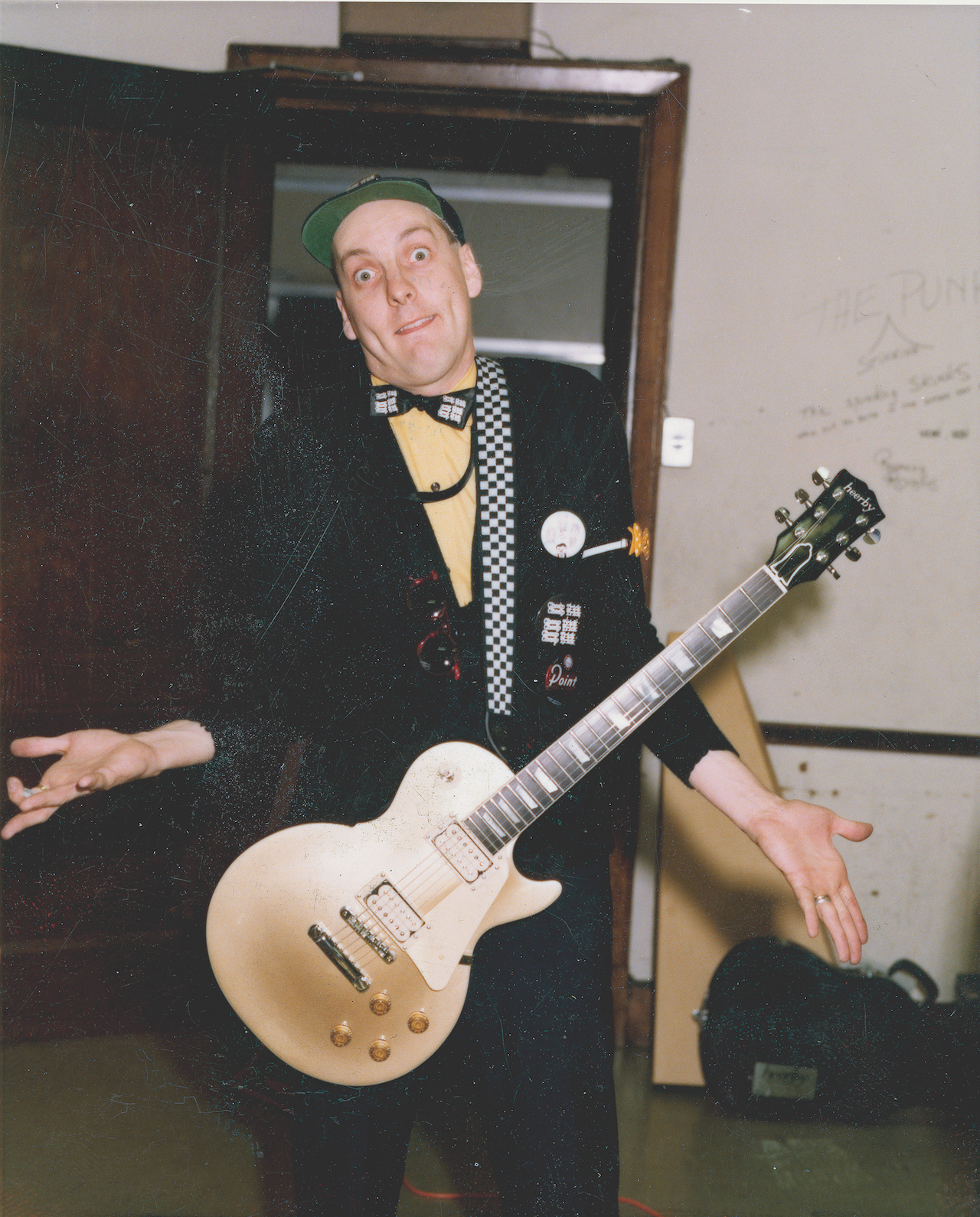

Oh, absolutely. As a matter of fact, my demonstration used to be I had a Les Paul goldtop. I’d walk into a music store and I would say to the guitar tech, “The neck pickup on a Les Paul is always louder than the bridge pickup.” I would play the neck pickup, and then I would switch to the Super Distortion and then look at them and go, “Not anymore.” Lo and behold, I literally never left the store without an order.

Besides the pickups, how else were you trying to expand your business? Simultaneously in that same period of time, I contacted Wayne Charvel, because Wayne was making these Les Paul jack plates that I saw in an ad in Guitar Player magazine. I called him up and said, “I’m Larry DiMarzio and I love your jack plates. Can I buy some to use in my shop? I’d also like to buy your jack plates and sell them as DiMarzio products.”

I always had a feeling for pizzazz and a little bit of something that had a look to it. I wanted to have a style for the company

I could have knocked them off, but that just wasn’t my hippie style. It’s your idea and you’re entitled to keep your idea. I just want to buy them from you.

We started a relationship at that point. Wayne was making bodies to some degree in the original Wayne Charvel shop. I had ideas about bodies too, because by then Fender had turned the Stratocaster body into what I refer to as the amoeba, where everything was rounded over.

What I wanted was tight contours. I wanted an edge and I wanted that clean line that they used to have. By the late ’50s, Fender really had those lines, and the cuts on the guitar and the weight of the body was really right.

So you added guitar bodies to the product line?

Yes. I basically spec’ed out the bodies that I wanted with Wayne, and we started selling them. And then, within a short period of time, Grover Jackson took over from Wayne, and we were buying bodies from Grover. I didn’t like Fender necks at that time. So I went over and designed a neck with Stewart Specter at Specter Basses. I was in the middle of a bunch of guys, and it was really cool to leave my office and go to Stewart’s, and we’d go have lunch and work on what we were doing with the guitar necks.

In my opinion, we built a better neck than Fender did at that time, because we kept making changes. I changed the radius to nine and a half inches, and I did that in probably the late ’70s. I also redesigned the Fender bridge to be narrower. Allan Holdsworth used that bridge for quite some time on his guitar.

You worked with Eddie Van Halen too. How did that happen?

You were seeing right at that period of time that there’s a relationship between the development of what I would refer to as the Superstrat: namely a Stratocaster body with a tremolo arm on it and a humbucker in the bridge position. That was really driven a lot by Eddie Van Halen. Everyone wanted to know what he was doing. He was a real tinkerer, and he messed around with a lot of things.

When I finally got a chance to work with Eddie in the ’90s, I realized that it’s almost intuitive on his part. My job was to deal with the technical aspect of stuff; his job was to point the finger in the direction he wanted it to go in.

The neat thing is that I was in a really good position with Eddie because he, [Ernie Ball lead designer] Dudley Gimpel and Sterling Ball, and Steve Blucher from DiMarzio already had a very good working relationship.

When I worked with Eddie in the ’90s, my job was to deal with the technical aspect of stuff; his was to point the finger in the direction he wanted it to go in

I did a photo shoot with Eddie early on, and the nice thing was that he knew who I was, so it made life a lot easier, as opposed to walking in cold as a photographer and doing a project. I didn’t know what to expect, but we talked guitars and gear and all that stuff for hours.

Everybody wanted to be Eddie’s best friend, and as a byproduct of knowing that, I just did my job and enjoyed the fact that he liked what we were doing, liked the sound of the [Music Man EVH Signature] guitar and liked the changes that we made, so it was really simple and very pleasant.

In a sense, the bulk of my relationship with Eddie was really making sure he looked good in the photos. I felt that that was part of my responsibility, because DiMarzio wasn’t using Eddie directly.

You had great stylistic ideas too, like using cream coils on the Super Distortion to make it stand out from regular humbuckers when the covers were taken off. And it worked like a charm. Everyone wanted that look of DiMarzios on their guitars.

I had that from growing up in New York and being around the city and the shop windows. I always had a feeling for pizzazz and a little bit of something that had a look to it. I wanted to have a style for the company.

Ace Frehley had three Super Distortions on his Les Paul, and suddenly Kiss was everywhere. That must have been amazing to see that happen with those guys, since you knew Gene and Paul.

I was excited for them, because you have me playing, Gene coming to the gigs, and me and him recording in the basement together. And Gene, by the way, was a big Leslie West fan. I remember playing back a tape and Gene leaning over and going, “Play it more like Leslie,” and I’d lay the part down again. This was like a two-track recorder in mom’s basement, just messing around with the direction he wanted it to go in.

With so many new guitarists on the scene these days, how do you incorporate their ideas for pickup designs?

Sometimes their ideas are similar to mine and sometimes their ideas are really different. I have to stay contemporary and current. The goal, of course, is not to turn into a dinosaur. We work with new people all the time, and because I do a lot of media advertising, I consider myself a marketing/advertising guy as well.

The last album cover I did is the Steve Vai cover with the Hydra guitar on it [Inviolate]. I knew that Steve was working on that guitar for quite some time. When I got a call to do the art for the album, I was like, “Can you send me some photos of what the guitar looks like?” That was primarily a Steve and Ibanez project. We were peripherally involved, as opposed to the PIA3761 guitar, where we were majorly involved during the whole development. It always varies. Some companies want us in there and working with them really closely, and other companies just have us make a pickup that the artist likes.

So sometimes it’s a subtle variation, and sometimes it’s like a complete ground-up build and design. So that’s a big variable. But what we like doing is working with people that are doing things that are different. For Gojira [guitarist, Christian Andreu] it’s a mahogany Fender Telecaster body, a maple neck with an ebony fingerboard and two humbuckers. Now that’s not so new, but it’s new enough. And of course, it’s got to sound good.

Who inspires you these days?

I like staying on top of everything, and I listen to all kinds of music. I’m not really locked into guitar players. I was paying attention to Dua Lipa 10 years ago because I thought she really understood MTV. From a marketing standpoint she has a lot of the right things in the right place. I’ve been listening to Caroline Polachek too. P.S. — Neither one of them play guitar.

For more info on Larry Dimarzio, the Super Distortion and his other range of products, check out his website

Art Thompson is Senior Editor of Guitar Player magazine. He has authored stories with numerous guitar greats including B.B. King, Prince and Scotty Moore and interviewed gear innovators such as Paul Reed Smith, Randall Smith and Gary Kramer. He also wrote the first book on vintage effects pedals, Stompbox. Art's busy performance schedule with three stylistically diverse groups provides ample opportunity to test-drive new guitars, amps and effects, many of which are featured in the pages of GP.

Guitar Center's Guitar-A-Thon is back, and it includes a colossal $600 off a Gibson Les Paul, $180 off a Fender Strat, and a slew of new exclusive models

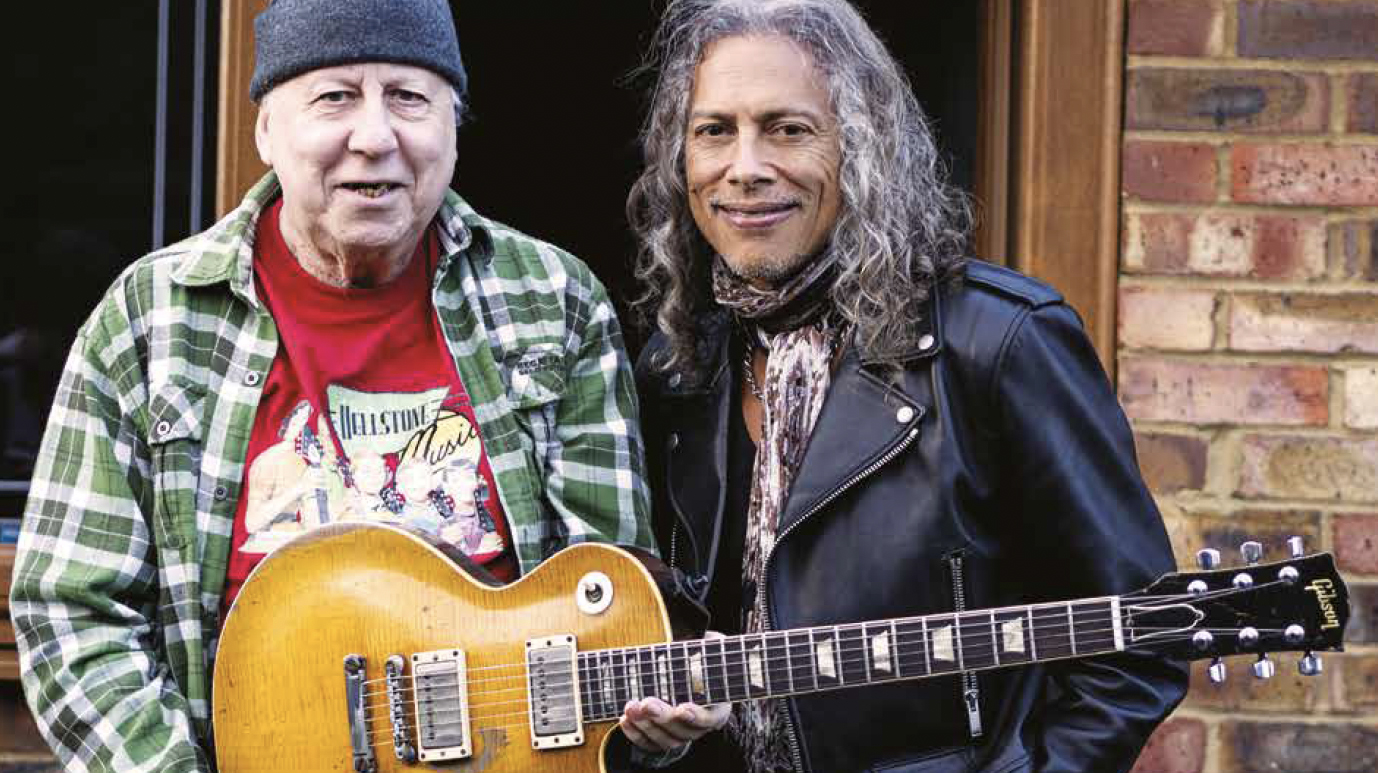

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models