“If You Can Imagine It, We Can Do It”: Framus Gives ‘Guitar Player’ an Eye-Opening Factory Tour

Once the biggest musical instrument maker in Europe and endorsed by the likes of John Lennon and Elvis Presley, the legendary brand’s HQ at Warwick in Germany is a temple of tonewood

***The following article appeared in the February 2019 issue of Guitar Player***

On a visit to the factory in Markneukirchen, Germany, where Framus electric guitars and Warwick basses are made, you can be sure you’ll learn what’s behind the creation of these quality instruments and get a first-hand look at some of the company’s extraordinary custom finishes being made.

What you might not anticipate is how much the subject of wood comes up. Of course wood is important to the sound and look of guitars and basses, and you would rightfully expect the luthiers at Framus and Warwick to pay particular attention to these details.

But, seriously, these guys are obsessed.

They’ve got more than 45 different types of the stuff, not counting all the different grades on hand. There’s bubinga, rosewood, ebony, wenge, camphor, flame maple and countless others. We are even shown mahogany that’s distinctively marked from having been used as a countertop in the production of parmesan cheese.

Although some of the wood we see is raw, its quality shows through. Tapping a random chunk of maple yields a high, hollow drum sound that hints at the acoustic properties it will one day impart to a Framus guitar.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Now part of Warwick GmbH, the Framus brand is legendary, having been founded in 1946 by Fred Wilfer, the father of owner Hans-Peter Wilfer. It was, in its time, the biggest musical instrument maker in Europe. Within years of its founding, the company’s guitars were in the hands of young musicians like John Lennon, Bill Wyman and Elvis Presley.

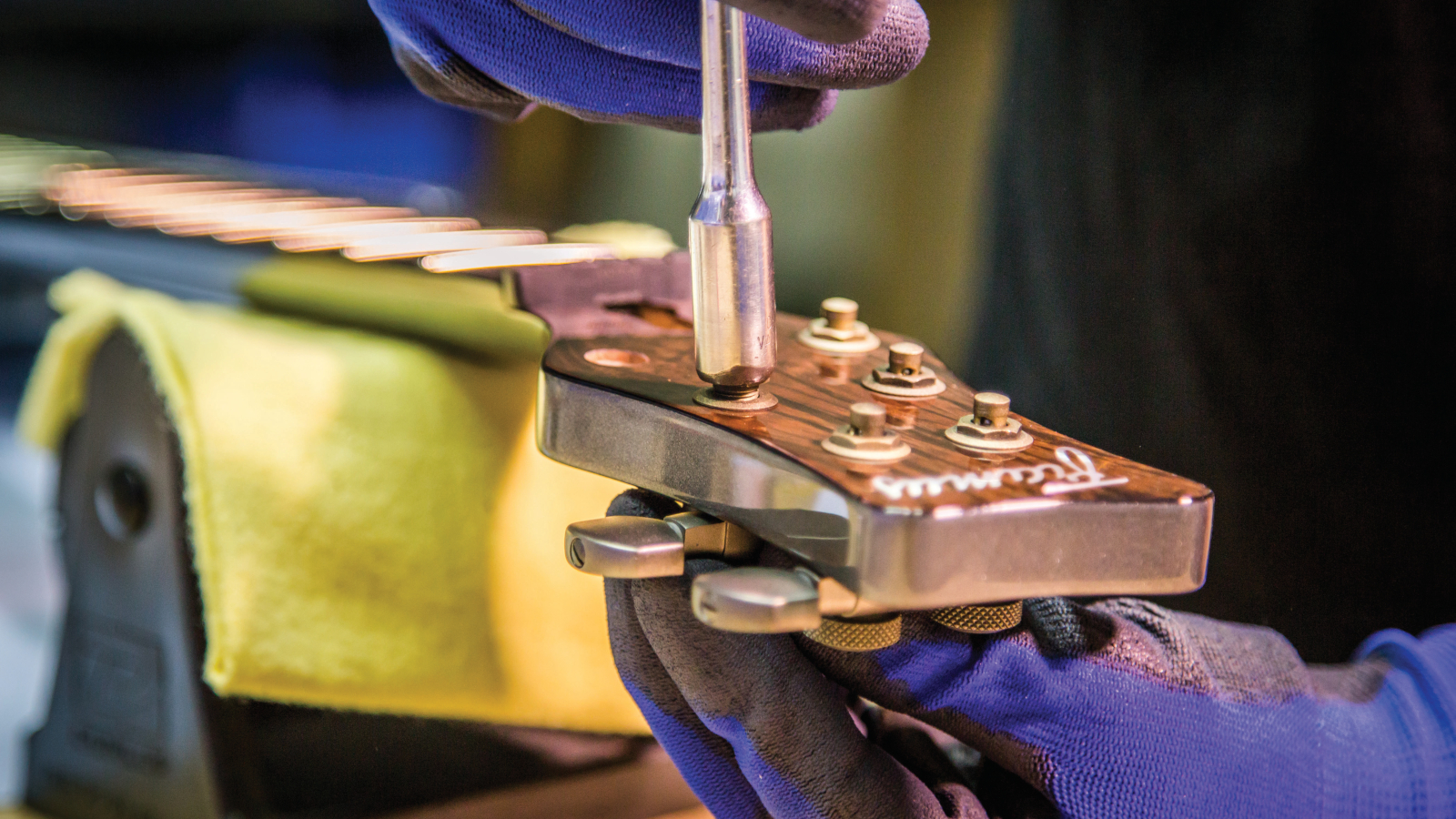

After going bankrupt in 1974, Framus came back with a new lineup in 1995 and, under Hans-Peter’s guidance, began ushering in innovations like its Invisible Fret Technology, which leaves two millimeters of wood at either end of each fret to increase stability and prevent twisting, as well as a bolt-on neck system that creates a solid bond between body and neck, and diamond-clear ultra-thin lacquer finishes.

But it all starts with the wood, and that wood is treated with care.

After the initial natural drying stage, it’s moved into a humidity- and temperature-controlled warehouse to complete an air-drying process that can last up to seven years. From that point onward, every room it passes through in the manufacturing process is a strictly controlled environment.

Wood not intended for the custom shop guitars is finished in a drying kiln. Marcus Spangler, the head of Warwick’s custom shop and the man responsible for all Framus and Warwick production, explains that the atmosphere in the kiln is initially kept humid and slowly made drier.

“This lets the wood dry all the way through,” Spangler says. Starting with completely arid conditions would damage it, because the outside would dry faster than the middle.

The dried wood is then sorted according to how much moisture remains in it. Pieces with similar humidity levels will eventually be used in the same guitar, so that any future expansion or contraction happens evenly to prevent damaging the instrument.

After the wood is dried, one of the first jobs is to assemble the correct grains to make a strong bolt-on neck. The center of the neck has a grain that runs up and down its length. It’s supported on either side by woods with grains that run diagonally, so that the natural properties of the instruments’ materials work together with its man-made structure to make it as strong as possible.

As it happens, much of the early process of making a Framus or Warwick instrument is automated. Necks and bodies appear almost magically from the clouds of sawdust thrown up by the factory’s CNC machining tools.

Though some of these jobs could be done more easily by hand, the company values the precision it offers, from the way the bodies are shaped to accommodate the bolt-on necks to how the sides of the bodies are pre-shaped to fit the soundboard, negating the need for to use clamps in assembly.

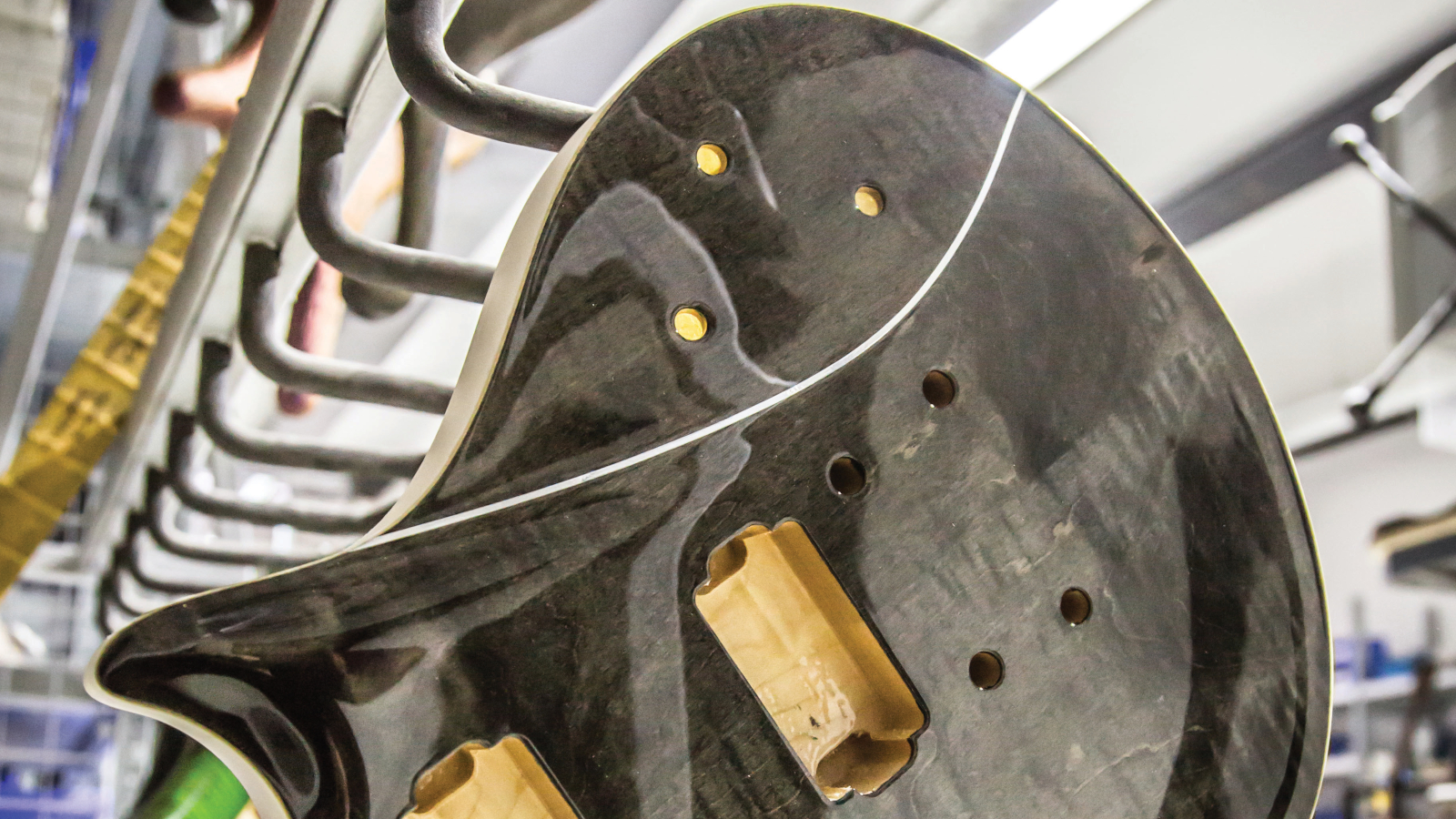

Once an instrument is put together, it’s hand finished in the same workshop used for custom shop work.

Having seen a batch of instruments assembled, we are treated to the sight of Warwick’s unique lacquering process. The company’s lacquer is much thinner than it was in the past, but it’s also hardier. To demonstrate the point, Spangler pours pure acetone onto a recently lacquered bass body. Two minutes later, it shows no sign of damage.

The new lacquer results in a better look too, since it’s dried by UV rather than a chemical process. This eliminates small bubbles and results in a finish that is perfectly clear. Most importantly, though, that lacquer allows the natural tone of Framus guitars and Warwick basses to ring out.

Top-shelf lacquers aren’t the end of Warwick’s finishing options of course. Do you want a guitar fully clad in stainless steel? They can do that for you.

Or maybe you’re like Devin Townsend and want an axe with an onboard smoke machine and laser show.

No problem.

“If you can imagine it, we can do it,” Spangler says. “And if what you want is not possible…we can do that too!”

“You can change nearly everything,” he offers in an interview following the tour. “Not the headstock or body shape, but everything else can be adjusted to your needs.”

Given his strong emphasis on sky-is-the-limit guitar design, what is Spangler’s proudest guitar creation? “I love the Idolmaker,” he says. “In my eyes it is the best combination of vintage and modern design.”

But of course he’s also proud of the wood, and Warwick’s ethical sourcing of materials.

“We’re known for using very exotic woods, and these woods come mainly from Africa,” he says. “We’ve been working together with companies based in Europe for years. They have pressure on them because they’re watched by the WWF [World Wildlife Fund for Nature]. For example, if they went into the forest and did damage, they would immediately have newspapers reporting that.

“But we also have conversations with suppliers, and they tell us what’s really happening. Europe is also a very small market for this product. More important is China. Forests run by our suppliers there are treated like those here in Europe. You go into a woodland, clean it up, make sure that plants are growing, and you only cut out as much as you replant or is regrowing. It’s really not like you go and cut everything down. We don’t buy wood from areas where that happens.”

It’s also important to Spangler that his team gets the credit they deserve.

“We have Katja, who selects the woods, and does it much better than I can,” he says. “She also takes care of the custom shop instruments as they go through production. Then we have Thomas, the pre-production manager who organizes everything. When a machine is broken he’s there to repair it. We have Christopher, who’s the CNC and CAT programmer, and we have Stefan and Libor, who are leveling frets and doing custom shop tweaks on the instruments, especially the necks. Michael makes things that you can’t do with the CNC – for example special inlays. Sebastian is our sprayer, and then of course we have the assembly guys, Marcel and Mani. They’ve been doing their jobs for years.”

The company’s attitude is possible thanks to this small and dedicated team.

“Although everybody thinks we are a big company with 1,000 employees and so on,” Spangler says, “at the end of the day, our production here in Germany is a process involving 15 people at the moment. It’s not big. All of our employees are proud of what they’re doing and they do it with passion. I think it’s very high end.”

That kind of dedication comes at a price of course, which can sometimes be a problem for the Framus and Warwick brands.

“People ask, ‘Why does this instrument cost $6,000?’” Spangler says. “But then you see the countless small changes and details, like the invisible frets that no other manufacturer is doing because they make no sense on a mass-production instrument. Or the work we do with CNC, which could be done faster by hand, but not so precisely.”

We’ve learned a lot on our tour, but one burning question remains: Will that parmesan-scented chunk of wood ever find its way into an instrument?

“Yes!” Spangler confirms with a smile. “We are making one for a customer in Japan.”

Visit Warwick for more information.

Guitar Center's Guitar-A-Thon is back, and it includes a colossal $600 off a Gibson Les Paul, $180 off a Fender Strat, and a slew of new exclusive models

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models