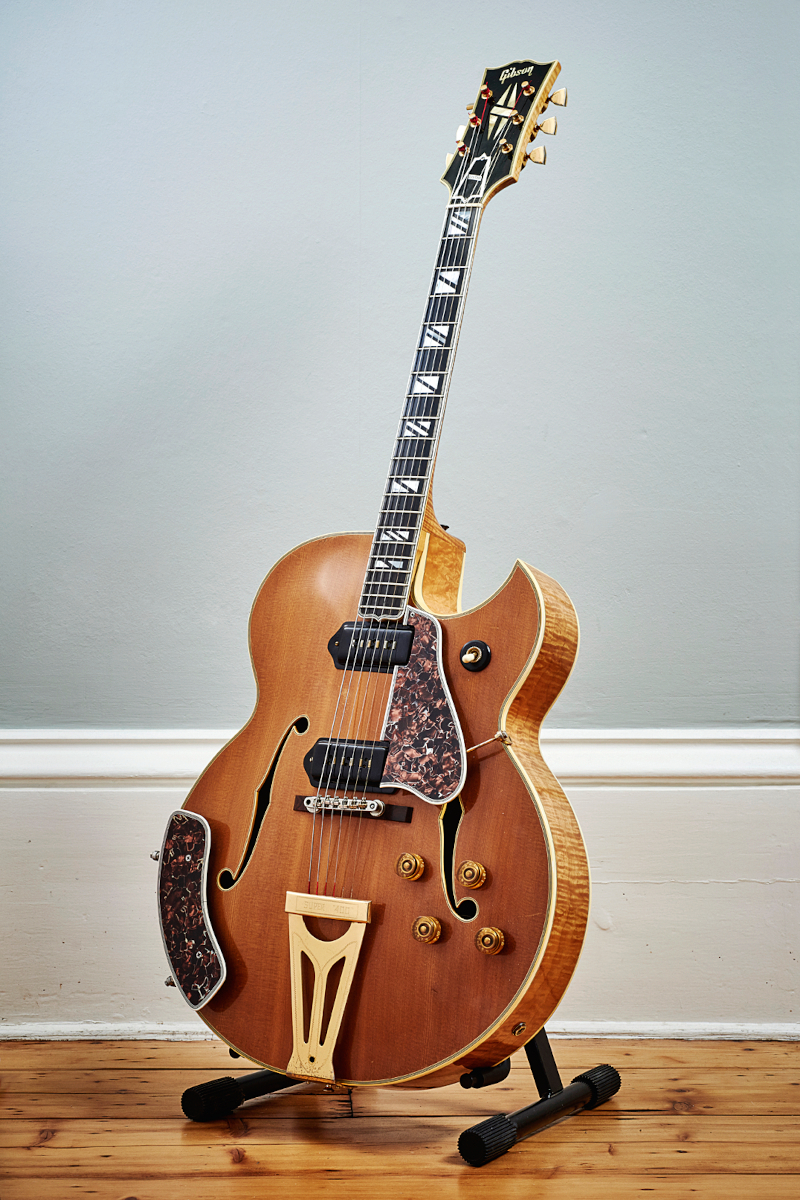

The History of the Gibson Super 400CES

We trace the evolution of these superlative guitars with jazzbox expert and author Dr Thomas A. Van Hoose

The Super 400CES is often regarded as Gibson’s crowning glory in jazzbox design and, following its release in 1951, it reigned supreme over the electric archtop market. After photographing a rare collection of examples from the ‘50s and early ‘60s in the U.K., we dropped a call over to archtop historian Dr Thomas A. Van Hoose in Texas to take a closer look at the model’s evolution.

A clinical psychologist by profession, Tom is also the author of The Gibson Super 400: Art of the Fine Guitar (Miller Freeman).

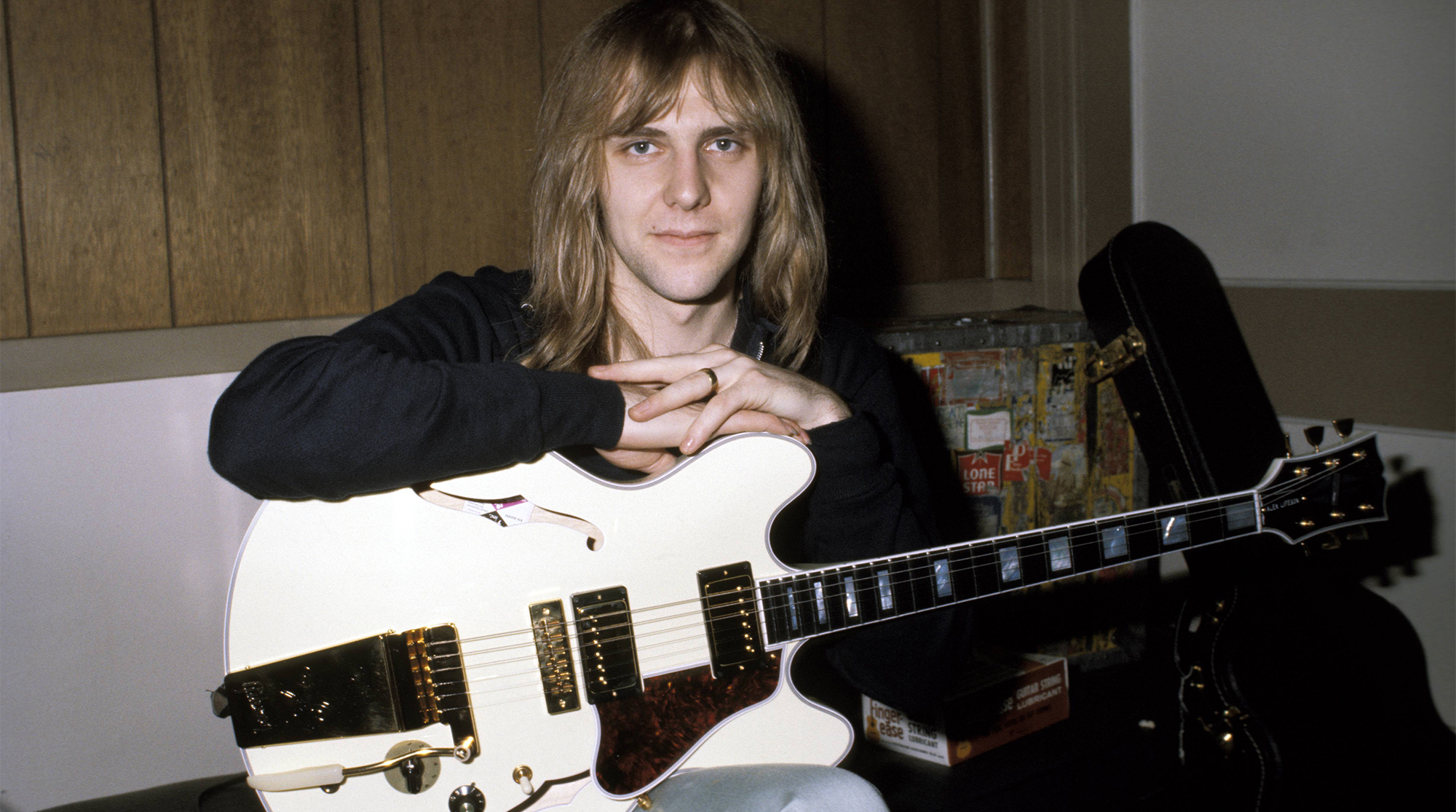

“The guitar has been a part of my professional life as far as I can remember,” says Tom. “I always kept a guitar or two in the office, sometimes small-scale ones so kids could play them, but it’s also therapeutic for me. I got involved with the Super 400 during the ‘60s when I was in college at the University of Texas. My band had a guitarist who was a very talented blues player and I asked him, ‘Where can I learn this stuff?’ so he took me to a record store to buy two albums, one was called Freddy King Goes Surfin’ and the other was an album by Kenny Burrell. And that’s when I heard something new: that jazzy blues sound. I noticed Kenny played a Super 400C and like any guitar worshipper I said, ‘I want to sound like him; I want to get one of those guitars.’

“My first one was a cutaway Super 400[C] acoustic from ’67,” he recalls. “I had a DeArmond Model 1100 [Rhythm Chief] pickup put on it and I learned to play some of Kenny Burrell’s arrangements. Later, I saw on another album cover he was playing a sharp [Florentine] cutaway Super 400CES [Cutaway Electric Spanish] and I thought, ‘Well, I’ve got to get one of those, too.’

“I found one down in Austin at Guitar Resurrection – a ’64 Super 400CES with a sharp cutaway and two humbuckers, just like Kenny’s. It was a gorgeous guitar! Of course, I didn’t quite sound like Kenny, but I learned and took lessons along the way. And as I went along, I thought, ‘I’ve seen different versions of this guitar.’ I was curious, so I started researching it.

The Super 400CES was the flagship of the company until the Citation came out in ’69

Thomas A. Van Hoose

“I started finding Super 400s at guitar shows in the ‘70s when the dealers were having a hard time selling them. They sold for $1,000 to $1,500 a piece back then; it didn’t matter whether they were acoustics or electrics, and the non-cutaways sold for even less. Very few people were using them and they were dead in the water.

“At that time, the perception of [Super 400s] was negative because the guitar scene had evolved away from their use in a pop music context. They had quite a heyday in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but then there were other major developments that became more and more popular, like the thinline ESes, Les Pauls and Fenders – they were more usable in a blues and rock ’n’ roll context because they don’t feed back as much and they’re easier to play.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Despite the rapid changes in popular music during the ‘50s and ‘60s, the Super 400CES remained Gibson’s pride and joy.

“The Super 400CES was the flagship of the company until the Citation came out in ’69,” says Tom. “It was Gibson’s most expensive guitar and it was a symbol as much as anything else. These flagship guitars of the Gibson company – the Super 400CES and L-5CES – were made as much to be a statement as they were to be musical instruments.

“Super 400s were made in small quantities and it took many hours to make them. Whereas an ES-335, for example, had presses that made those [laminate] tops and backs, Super 400 tops were carved. There were no shortcuts. The bending of the sides and fitting it all together, hand-carving the neck, the assembly, applying all those different layers of binding, the finish – it just took time. [Gibson] never said it, but it was a case of, ‘We’ve got the biggest. We’ve got the best. Ours is the most ornate. Ours is the most expensive.’

“Super 400s were expensive, but more to the point they’re big. They first came out in 1934 as an acoustic, at a time when money was hard to come by. America was just starting to come out of the Great Depression and 400 bucks for a guitar was like buying a car back then! Gibson must have been very optimistic, but they were in heated competition with Epiphone at the time. The two companies were trying to top each other every year by coming out with guitars that were bigger or more ornate. The Super 400 is an 18-inch-wide archtop – arguably the first one like that – and so, of course, Epiphone came out with the Emperor [in 1935], which is 18½ inches [wide].”

Soon after Gibson’s battle for size reached its conclusion with the Super 400, in 1936 the war for volume escalated to the next level with the release of its debut ‘Electric Spanish’ guitar, the ES-150.

“The ES-150 was a breakout guitar,” says Tom. “When people heard Charlie Christian using one and playing his solos as loud as anybody else in the orchestra, they were just amazed – it was like he was playing a saxophone. Then they made the larger version [in 1939], the ES-250, which is really rare. It’s got a 17-inch-[wide] body, the Charlie Christian pickup and a carved top. That was the antecedent to the Super 400 and the L-5 electrics.”

Before World War II put a temporary halt on electric building, Gibson had started to explore electrifying the Super 400.

“They had these pickups that you could attach to the pickguards,” says Tom, “and folks were using those because they wanted to be heard. Like Charlie Christian said, ‘I want to hear myself!’ [As early as 1939] they also made a few Super 400 Premiere [pre-war cutaway] guitars with a diagonal factory-fitted electric pickup. That was the forerunner of the Super 400CES. I had one that Gibson verified was original. It didn’t sound that great, but you could plug it in and turn it up!”

After the war ended, electric guitar production at Gibson recommenced in earnest with a new line of models equipped with the company’s recently developed P-90 pickup.

“Gibson started ramping up production again in ’47,” says Tom. “The music that was coming up after the war was becoming more amplified and folks wanted electric guitars. They had the ES-300 and then they came out with the ES-350, which was the cutaway version. Then there was the three-pickup ES-5 in ’49, which was the final precursor to the L-5CES and the Super 400CES. These were 17-inch laminate-body guitars – not a carved body but they were big.

“However, the one that really popularized the electric archtop was the ES-175 and that also came out in 1949. Boy, that one lit a fire under people because it sounded great, it was lightweight and it was relatively inexpensive. After that, in 1951 Gibson decided they wanted to amplify the L-5 and Super 400 models, so they came out with the L-5CES and Super 400CES with twin P-90s. And then we were off to the races!

“There are some differences between the Super 400 acoustic and Super 400CES that are not apparent because they’re inside the guitar. Gibson learned very quickly that they had to carve the tops of the CESes thicker to inhibit feedback to some extent. The acoustics have thinner tops so that they vibrate more and you can hear them better. The CESes are also parallel-braced, but they moved them out a little further away from each other to accommodate for the pickup cutouts.

“They also put these little cross braces on either side of the pickup to connect the parallel braces and stiffen the top even more. That internal construction made a difference and the guitars are noticeably heavier. You might not think it would matter that much, but you can feel it. During the first couple of years, from ’51 to ’53, Super 400CESes had P-90s and then they went to the Alnico pickups. Those went from ’54 to ’57 when they started introducing the PAF [humbucker].

“The 1950s Super 400s have rounder, thicker necks than later guitars – although they’re not chunky like a ’58 ’Burst – and a 1 11/16-inches nut width. From ’60 to ’62, the necks were a little flatter and then they went back to the rounder shape but not quite as thick. The Super 400CESes, L-5CESes and other models were pretty much in step when it came to the changing neck profiles. The consistency is there for different eras. That is, if we’re talking about say the sharp cutaway CESes from ’60 to ’64, they’re very consistent. The major dimensions stayed the same – the body width and depth and the scale length – but the only difference with the ’60 to ’64 guitars is the necks got a little rounder in ’63 to ’64.

“From ’65 to ’66, they started to get narrower at the nut: 1 11/16 inches was the standard width and then it went to 1 9/16 inches. That was a noticeable difference. A lot of folks don’t like them because it crowds the strings together too much. Gibson got a lot of negative feedback about that and so they changed it back to 1 11/16 inches in late 1969.”

Such changes in design were often prompted by suggestions from players, one of whom had a big influence on this model…

“Kenny Burrell never had a Gibson signature model, but going by what Ted McCarty told me he was the main influencer in terms of Gibson going from the rounded [Venetian] cutaway to the sharp Florentine cutaway in mid-1960,” remembers Tom. “Kenny liked playing way up on the fretboard – he’d had ES-175s and you could easily get up there on those –and so Gibson switched cutaways based on his recommendation. They made that sharp cutaway version for 10 years before going back to the rounded cutaway version again [in 1969].

“Super 400s had a longer scale length of 25½ inches [from 1937], whereas the ES-175 is 24¾ inches, like a Les Paul or a 335, and that adds something to the tone of the guitar, especially when playing complex chords. Sometimes you need to stretch a bit to play them, but it gives you more room to play and it has more pluses than minuses, I think.

“The rear [bridge] pickup on Super 400CESes has a brighter sound because they’re close to the bridge and the string tension is tighter. You can turn on the rear pickup and pick right over the pickup close to the bridge and you get that cool thin sound, but if you want to sound like Kenny Burrell, you might want to play over the front [neck] pickup, where he picks, because it’s more warmer-sounding.

“George Benson also played one very early on – you see pictures of him playing live and on his album covers with a Super 400CES just like Kenny’s. You also had [country musicians] like Merle Travis and Hank Thompson playing them because they looked great and they were easy to strum. Scotty Moore had an ES-295, an L-5CES, and then he got a couple of Super 400 CESes, one of which Elvis used on his [1968] Comeback Special.

“Gibson kept the Super 400CES in production for a long time and, although it dwindled with changing musical trends, people still want new versions of the old guitars and they want to be able to order them with custom touches.”

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.

Guitar Center's Guitar-A-Thon is back, and it includes a colossal $600 off a Gibson Les Paul, $180 off a Fender Strat, and a slew of new exclusive models

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models