Caught by the fuzz: The story of Electro-Harmonix’s tooth-rattling Big Muff, the stompbox guitarists have been falling in love with since the 1960s

Big Muff fanboys including Jack White, Dave Gilmour and The Edge, discover how Electro-Harmonix’s fuzzbox changed electric guitars forever

The fuzz box hit the scene in the early 1960s, and by the latter part of the decade nearly every gear manufacturer was promoting their own version of the effect. But the most popular American-made fuzz pedal of all time, the Electro-Harmonix Big Muff, wasn’t released until the end of the 1960s or possibly the very start of the next decade. Remarkably, it very quickly became a favorite of guitarists everywhere.

That hairy form of distortion known as fuzz was first boxed in a compact solid-state device when Nashville studio engineer Glenn Snoddy devised a circuit to re-create the enticingly clipped sound of a faulty mixer channel.

His invention was subsequently released as the Maestro Fuzz Tone pedal in late 1962 or early ’63. Within a year or so, English engineer Roger Mayer was building custom fuzz pedals for London guitarists, and British makers Sola Sound and Arbiter took their own creations to market in the years following that.

Back in New York City, however, Mike Matthews, an aspiring rock keyboard player working a day job as an electrical engineer for IBM, decided the market was far from oversaturated and started getting his own pedal ideas together.

Some time around 1966 or ’67, Matthews and an IBM colleague concocted a fuzz pedal that sold in significant numbers as the Guild Foxy Lady. Additional work with Bell Labs engineer Bob Myer led Matthews to create the simple LPB1 preamp, which was housed in a small enclosure that plugged straight into a guitar output.

It became the debut product of Electro-Harmonix upon the company’s inception, in 1968. It was followed by the Muff Fuzz, a simple two-transistor dirt box contained in a similar compact case.

The quest to make an even more powerful fuzz — and place it inside a floor unit with a convenient foot switch — led them to design the Big Muff π. Matthews and Myer have both said they released the pedal in 1969, and early documentation shows Electro-Harmonix was advertising the Big Muff in 1970.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Matthews claimed to have a copy of an order from Carlos Santana with a 1970 date and said he’d seen Jimi Hendrix use one in the studio in 1970 after someone tipped him off that the guitarist purchased the pedal from Manny’s Music.

Reliable accounts indicate that full production only ramped up in 1971. The excellent example seen here of an early “triangle” Muff — so called for the shape described by its control layout — was built in 1972. Those controls include volume, sustain (a.k.a. gain, or fuzz) and tone, as well as a sliding on/off power switch, included in an age when pedal makers weren’t yet using switching input jacks.

Often referred to as the second version of the V1 Big Muff, it replaced a debutante pedal that had the power switch built into the volume potentiometer and on which the tone control was labeled “fuzz,” although it performed the same function.

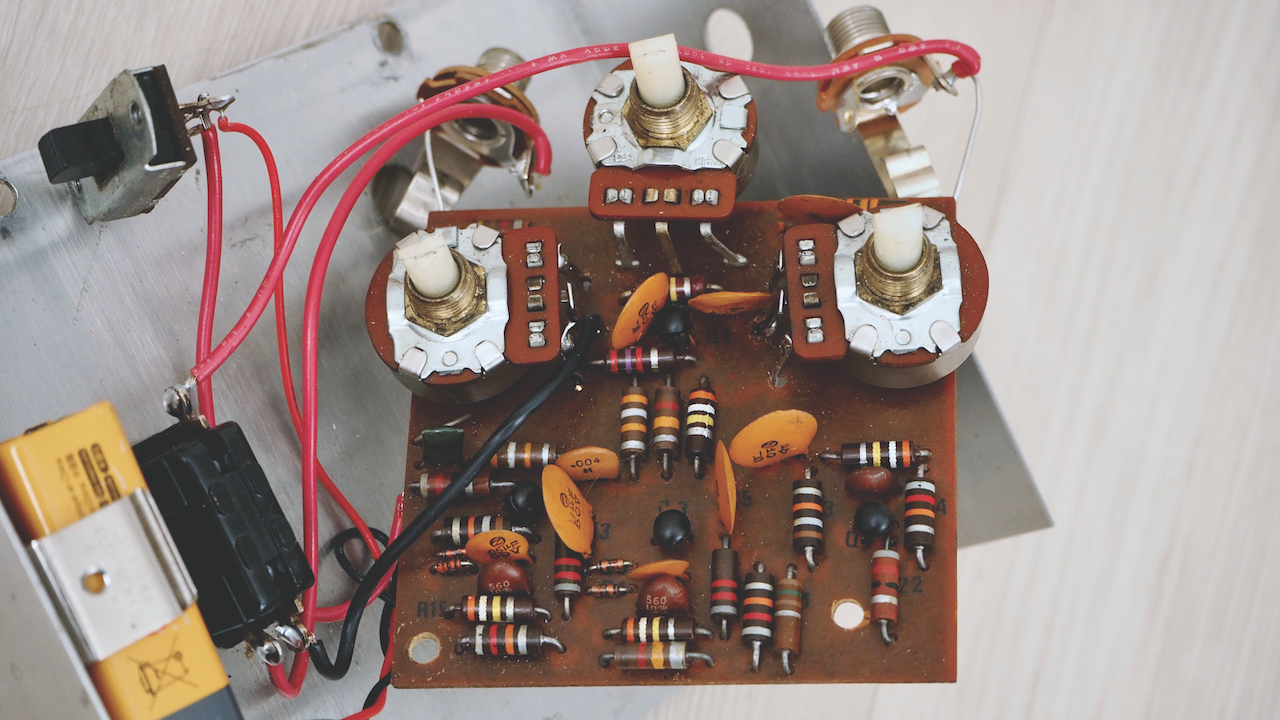

This example’s distortion is generated by four rare PNP FS37000 silicon transistors from Fairchild Semiconductor (sometimes purported to be re-labeled variations on the more common 2N5133), which in this iteration produced a fuzz sound that is thick, warm and smooth, yet with good articulation.

Although the 1972 triangle Big Muff is constructed with a rudimentary printed circuit board (PCB), its components are hand-soldered to that foundation and include several ceramic disc and poly film capacitors, carbon-comp resistors and two pairs of diodes, in addition to the essential transistors.

The makes and values of these components changed frequently, with the result that the tone of early Big Muffs often differed slightly from one pedal to the next.

The V3 Big Muff of 1973 saw the introduction of the three-in-line controls and brought the iconic “ram’s head” graphic to the enclosure — first printed in violet, then in black ink — along with red ink for the Big Muff logo. The V4 had red bubble letters and a black field around the lower part of the pedal, a look that was retained for several years.

Supply-chain issues and an impactful worker’s strike led to Electro-Harmonix’s bankruptcy in 1984, putting a period at the end of the development of the Big Muff that had lasted nearly a decade and a half.

“After that,” Matthews told me in 2004, “I helped Akai get their sampler program off the ground and developed some wireless products. Then I got sidetracked and involved with vacuum tubes from Russia.”

That connection not only helped Matthews develop the Sovtek tube brand — it also led him to produce several popular E-H pedals there, including the Big Muff. He first edged toward a reintroduction of the legendary fuzz via the Mike Matthews Red Army Overdrive, manufactured in St. Petersburg and released around 1991 or ’92.

Soon after, Matthews applied the Sovtek brand to a range of Russian-made Big Muff pedals, which used the same variation of the Big Muff circuit found in the Red Army Overdrive but carried the Electro-Harmonix name.

Originally housed in enclosures screened with “Civil War” graphics, so called for their contrasting blue and grey ink and 19th century font, these morphed into the BMP tank-colored “green Russian” pedals that are probably the best known among E-H’s eastern-bloc production.

Increasing demand for the Big Muff and its variations led Matthews to reintroduce a New York City–made pedal in 2000. With a circuit redesigned by Fran Blanche, formerly of the boutique pedal maker Frantone, the modern Big Muff hit the ground in red-and-black graphics, and this seminal fuzz circuit — in myriad further variations — has been a mainstay of the Electro-Harmonix lineup ever since.

Famous Big Muff users are many, but a short list includes J. Mascis, Jack White, Ernie Isley, David Gilmour, Dan Auerbach and The Edge.

Essential ingredients

- Triangular knob layout

- Controls for volume, sustain and tone

- Four Fairchild FS37000 silicon transistors

- Separate power switch

- Printed circuit board with hand-soldered components

For more information visit Electro-Harmonix

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models

“A good example of how, as artists, you have to blindly move forward with crazy ideas”: The story of Joe Satriani’s showstopping Crystal Planet Ibanez JS prototype – which has just sold for $10,000