Developed by Leo Fender the Music Man Sabre I is a Sound Sculptor that Cuts Like a Knife

This piece of classic gear may be of exceptional pedigree but is no dog.

Since its Acquisition by Ernie Ball in 1984, Music Man has released an impressive number of star-endorsed models and attained a firm standing among the ranks of highly regarded, U.S.-made electric guitars.

Such was the intention of the company when it was founded in the 1970s, even if it didn’t entirely go that way at first. Details of Music Man’s early history, including ownership, design credits and who made what, remain confusing to many, and have occasionally been misrepresented over the years, but it’s not too hard to untangle the basic threads of how this groundbreaking Sabre I guitar came to be, well before Ernie Ball was in the picture.

When discussing Music Man’s early history, what grabs most guitar fanatics’ attention is Leo Fender’s involvement. In fact, the origins of the workshop that built these guitars goes back even further than the founding of Music Man, and dates directly to Leo’s stealthy post-Fender endeavors.

After selling the Fender Electric Instrument Co. to CBS at the end of ’64 and turning over the keys in early ’65, Leo was bound to a 10-year noncompete clause. But if he couldn’t manufacture and sell his own competing products, there was nothing wrong with developing ideas for future use, so in 1966 he founded CLF Research (for Clarence Leo Fender) for just that purpose.

In 1971, Fender’s former associates Tom Walker and Forrest White founded Tri-Sonic, which, after briefly operating as Musitek, changed its name to Music Man In 1974. That same year, the first Music Man amplifiers hit the market, and in 1975, with the expiration of his restrictions from the CBS deal, Leo came onboard as president.

While Walker’s branch of the operation was responsible for the amplifiers from the mid to late ’70s, CLF made the guitars. The StingRay guitar and bass were introduced in 1976, and the Sabre followed another year or so after.

The two six-string guitars grabbed some attention when they hit the market, but the uptake among professional musicians wasn’t much to write home about. The StingRay bass – whether by fluke or by intention – seemed to have been perfectly conceived for emerging sounds of the day and was an overnight success.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Legend has it Leo was designing his guitars and basses to be brighter and brighter through the ’60s and ’70s, largely because he was becoming hard of hearing. As a result, some players found the instruments a little harsh and shrill, but the StingRay bass landed just in time to ride the wave of bright, snappy slap-bass styles prominent in funk and disco of the era, and it became a latter-day classic as a result.

Music Man electric guitars and basses were arguably better made than the Fenders of the mid to late ’70s, and this perception of quality – and of being “Leo Fender’s latest creations” – helped propel them in the market. Music Man released the original Sabre I and Sabre II models around late 1977 and offered them until 1980 or so.

Other than the clearly Fender-derived body and headstock shapes, CLF engineering touchstones are seen in the three-bolt neck attachment with hex-key tilt adjustment point, and the “bullet” truss-rod adjustment nut at the headstock end. These had already become the calling cards of the less-loved Fender Stratocasters of the ’70s, but Leo was sticking with their veracity from a design standpoint, and they arguably made more sense on entirely new makes and models.

Otherwise, major innovations were found in the dual humbucking pickups; an onboard preamp that offered independent active bass, treble and volume controls, a bright switch, a phase switch, and a low-impedance output; and a patented new bridge design with a sustain-enhancing brass base and individually adjustable saddles.

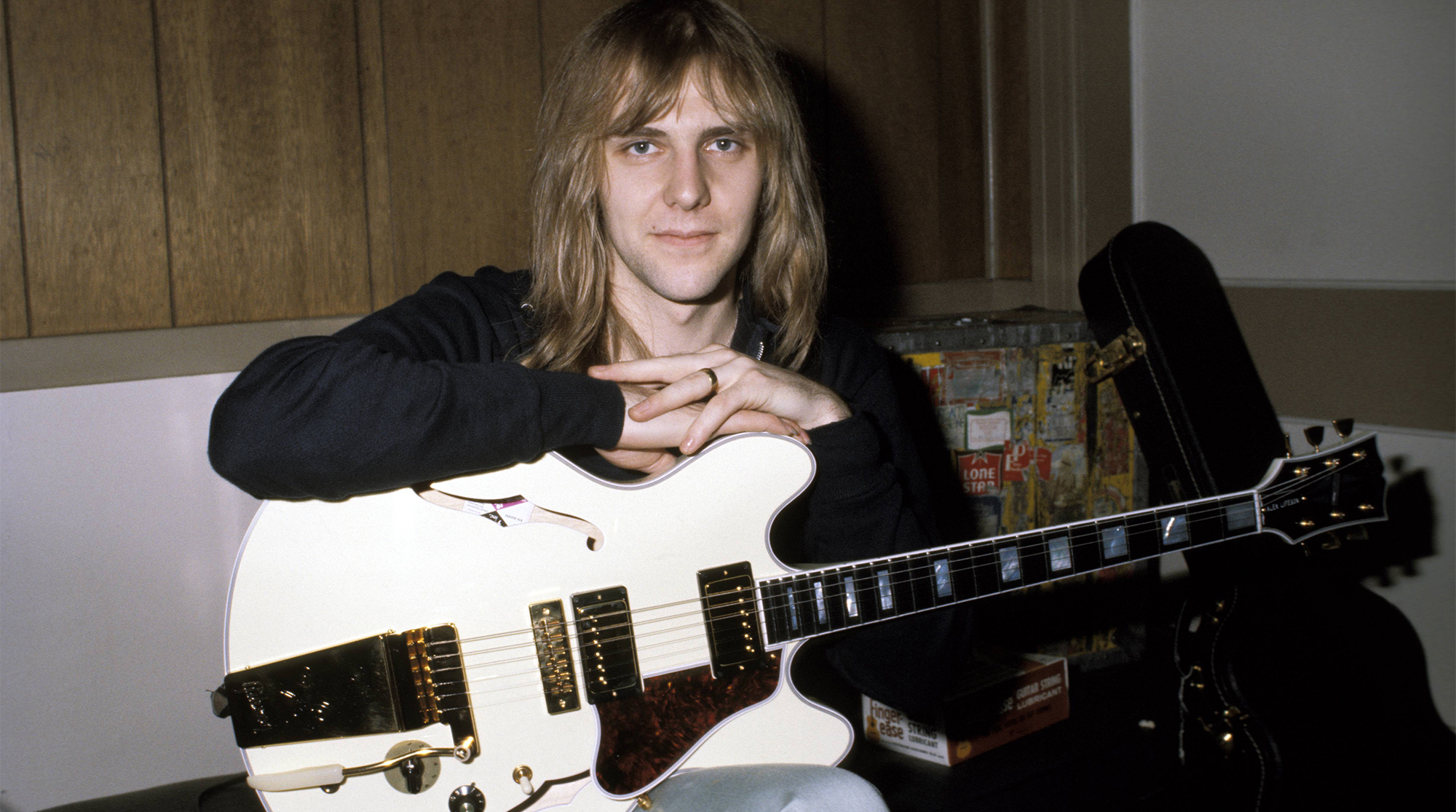

The pickups were narrower than traditional Gibson humbuckers to allow more picking room, and the neck and bridge units were made different lengths to position the pole pieces more precisely beneath the strings. All that, and the Sabre came in two models, although only the necks were different: the I, seen here, had jumbo frets and a 12-inch fingerboard radius for contemporary rock players, and the II had narrower frets and a 7.5-inch radius “for comfortable, untiring, country-style fingering,” as the ads of the day stated.

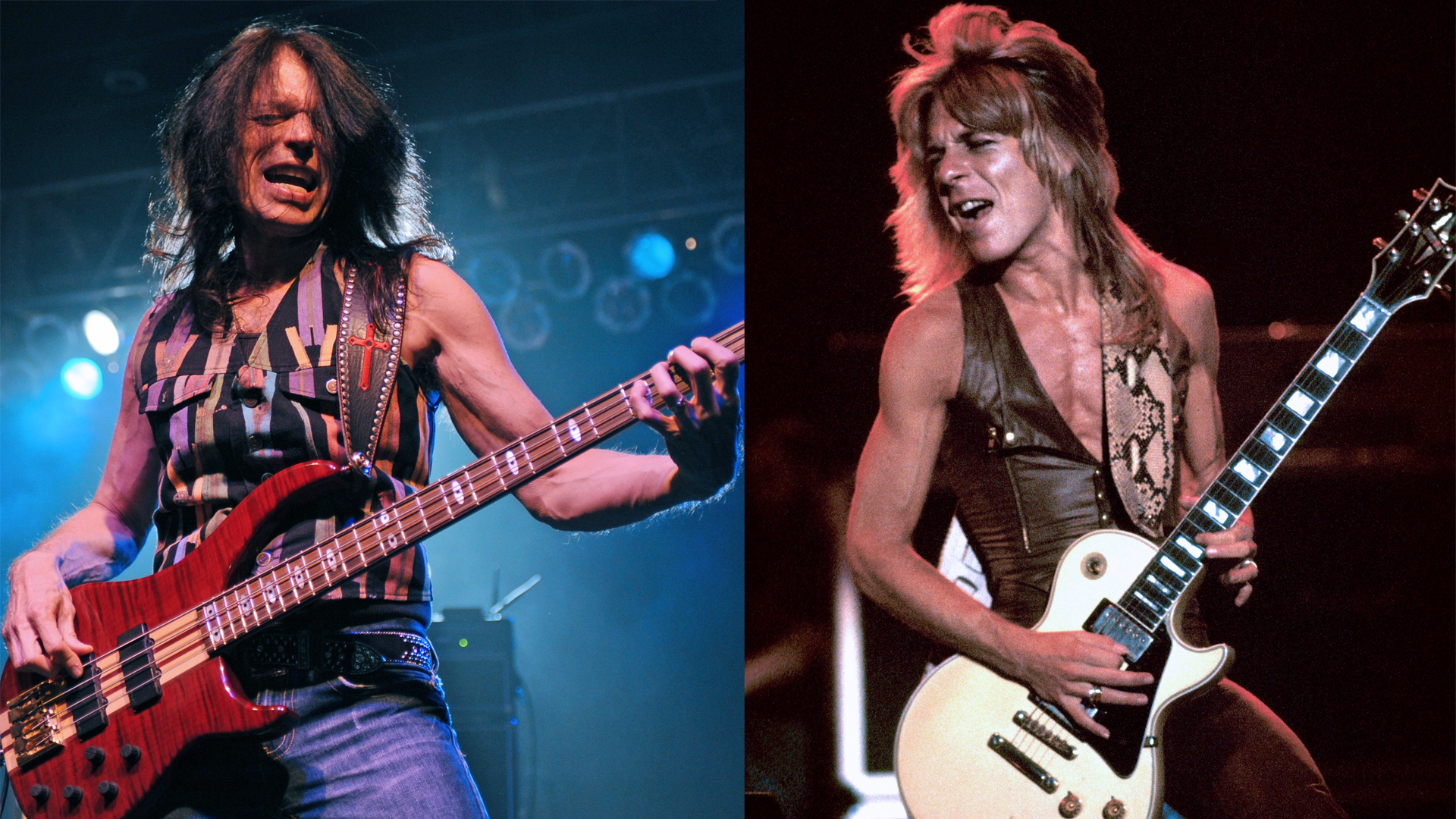

Notable early Music Man guitarists are thin on the ground compared to the stars – including Pino Palladino, Flea, Cliff Williams and Kim Deal – who played the StingRay bass. German guitarist Carl Carlton played a StingRay guitar with Vitesse in the late ’70s before joining Mink DeVille and, later, Carl Palmer and Eric Burdon and the Animals. Alex Weir wielded white- and natural-finished Sabre I examples with the Brothers Johnson in the ’70s and then with Stop Making Sense-era Talking Heads, as seen in the Jonathan Demme-directed 1984 concert film of the same name.

If you lay your hands on a late-’70s Sabre, be aware that the active electronics and powerful, bright-leaning humbuckers can lead to harsh sounds when used injudiciously. But when used right, those same features allow everything from snappy funk and jangle for rhythm work to warm, rich, meaty girth for rock chunk and solos. It’s a powerful sound sculptor, and needs to be treated as such.

Leo Fender severed his Music Man connections around 1980 or so, and shortly after co-founded G&L with George Fullerton. Still keen on many of the design ideas he’d brought to the Music Man guitars, he ported several signature touches over to the early G&L efforts. Check out an early G&L F-100, for example, and you’ll find similar humbucking pickups, nearly identical active electronics, and the Leo-certified three-bolt neck attachment and “bullet” truss-rod nut.

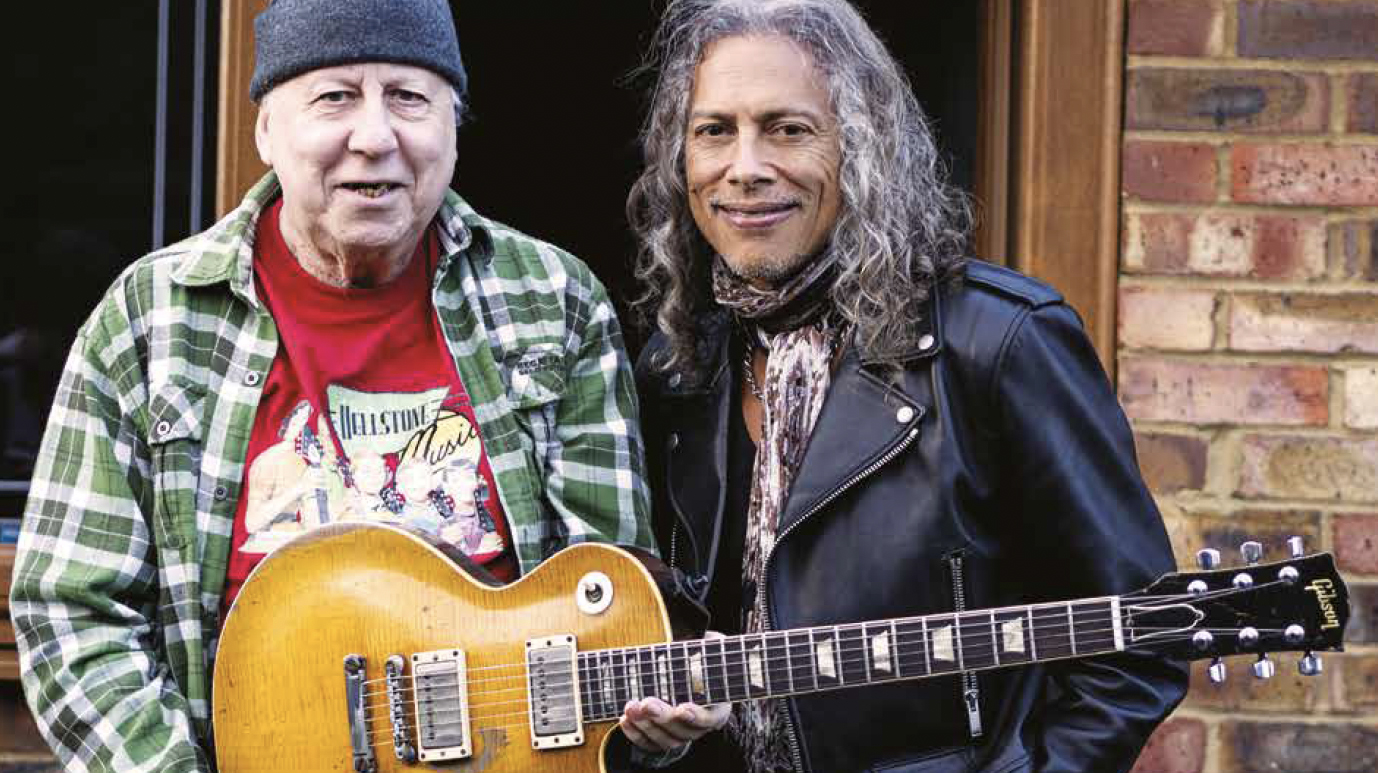

String-and-accessories maker Ernie Ball took over Music Man in 1984 and spearheaded changes that helped the company live up to its potential. The amps were dropped, but a new guitar and bass lineup, improved quality control and a long list of star endorsements – including Edward Van Halen, Steve Morse, Keith Richards, Albert Lee, Steve Lukather and many others – were added, helping to ensure Music Man’s place in the pantheon of pro-grade electric-guitar makers.

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.

Guitar Center's Guitar-A-Thon is back, and it includes a colossal $600 off a Gibson Les Paul, $180 off a Fender Strat, and a slew of new exclusive models

"We tried every guitar for weeks, and nothing would fit. And then, one day, we pulled this out." Mike Campbell on his "Red Dog" Telecaster, the guitar behind Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers' "Refugee" and the focus of two new Fender tribute models