Classic Gear: Roger Mayer’s Octavia Pedal

Mayer’s rocket-inspired pedal launched the sound of rock guitar into the stratosphere.

With its fuzzy, synth-like octave-up sound, Roger Mayer’s Octavia pedal was one of the most radical guitar effects to emerge in the late 1960s.

The pedal was made legendary thanks to its creative use by Jimi Hendrix, but the original device was never commercially produced at the time, existing only as a handful of custom-made units created by its inventor.

Mayer’s reluctance to take the pedal into production left the door open for early ’70s imitators like Tycobrahe, a notable copycat who even cadged Mayer’s name for its pedal.

As it happens, Mayer’s roots go far deeper into the London music scene of the ’60s, and his electronics training came in a more intense and elite form than that of most experimenters who were cobbling together solid-state effects back in the day.

Growing up in southwest London, Mayer was an avid music fan and learned to play guitar, which helped forge his friendships with Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and others on the local scene.

Inclined toward engineering, he had already started building treble boosters and experimenting with guitar tones while still in school, but his training became far more serious with six years at university, where he studied both mechanical and electrical engineering. After graduation, he went to work at the top-secret Admiralty Research Laboratories in Teddington, just down the road from his home turf.

“We were involved in vibrational acoustic analysis [for, among other things, submarine detection], which is half engineering and half electronics,” Mayer told me during our chats in 2003 for the book Guitar Effects Pedals: The Practical Handbook. “You’ve got all the subsequent vibrational and acoustical analysis of it using pickups, using all sorts of transducers and other equipment.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Not surprisingly, the techniques employed in this endeavor involved state-of-the-art circuitry, the mastery of which made effects-pedal design a doddle for him. In his spare time, Mayer stayed involved in the music scene and remained tight with several players who had become professional musicians.

In 1964, he built fuzz pedals for Jimmy Page and “Big” Jim Sullivan, the latter of whom used it on P.J. Proby’s number-one hit “Hold Me.” Charting nearly a year before Keith Richards slathered his Maestro Fuzz-Tone all over the hook to the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” the song is widely regarded as the first instance of recorded fuzz in England.

A couple of years later, Mayer’s sideline in effects pedals led him to befriend a certain left-handed Strat-playing newcomer on the scene, who’d arrived from the United States.

After meeting Jimi Hendrix on January 11, 1967, Mayer gave one of his early Octavia pedals to the guitarist, who sometimes referred to it as the Octavio (the originals were never labeled). Hendrix used the device on his solo for “Purple Haze,” recorded three weeks later.

Mayer eventually became a combined studio and tour tech and personal “sound creator” for Hendrix, yet he never considered cashing in on his designs by producing them for wider sale.

“When I made the Octavia for him, we made a few, like maybe half a dozen or so,” Mayer explained. “But when I went to live in America, I went straight into manufacturing recording studio electronics…and being involved in the start-up of the Record Plant and Electric Lady, and all that sort of stuff, so I wasn’t into making little guitar boxes. The only time we’d make a few guitar boxes for people would be for famous players, not anything available commercially in the music store.”

Through the ’70s, Mayer worked in the studio with a host of stars, including Bob Marley and the Wailers, and Stevie Wonder, for whom he built analog synthesizers, but his attitude toward the commercial pedal market began to change in the latter part of the decade.

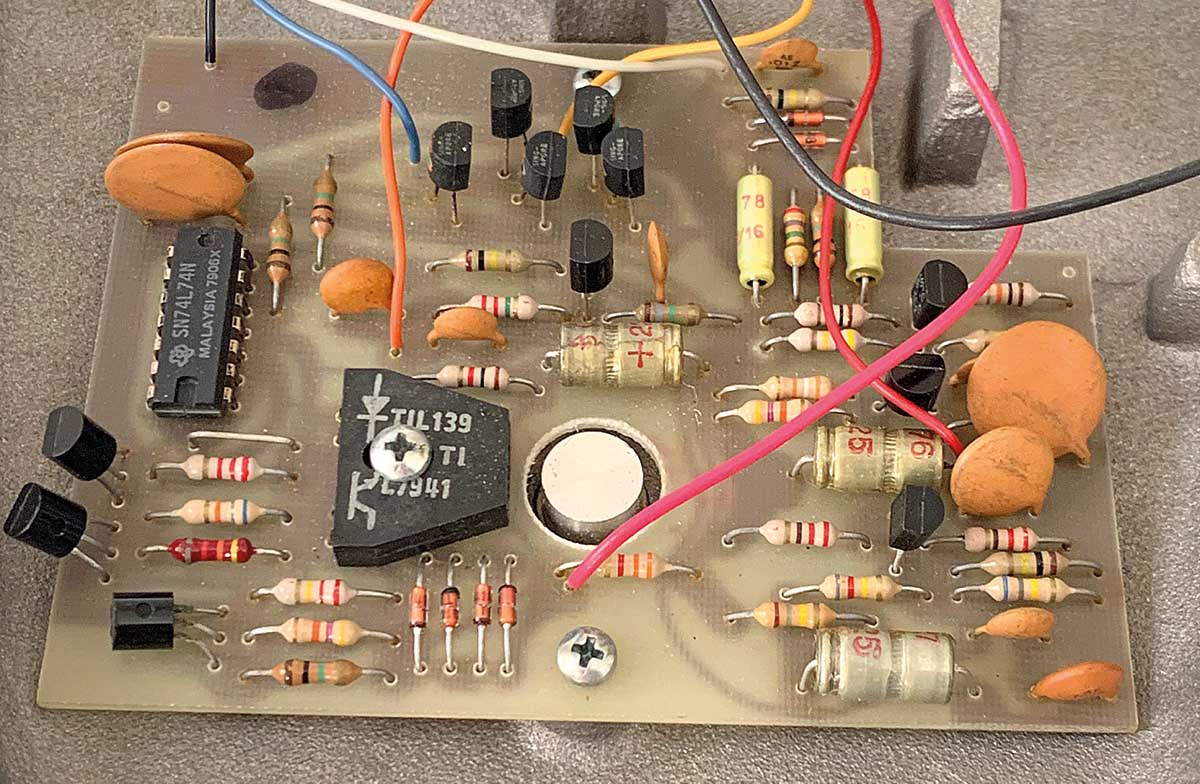

Around 1978 or ’79, he designed his iconic “rocket” enclosure, gave it a high-tech silent optical switch, and loaded it with his Octavia circuit. The first runs for the commercial market were made in the U.S. before he departed New York to return to England in 1980. In the early ’80s, Mayer sold the Axis Fuzz, Metal Fuzz, and Mongoose using the same enclosure.

“After a period, some people said they liked the snap-action of the switch, and this and that,” Mayer explained, “so we put a different switch in it, which was slightly cheaper to produce than the optical switch anyway.”

The Octavia’s circuit is itself a strange and clever beast, which Mayer describes as being simultaneously quite simple and rather mind boggling.

“I was just thinking about doubling the frequency and different techniques, and we came across a technique that, looking at it simplistically, it almost acts like a mirror,” he explained. “It doubles the number of images of the note. And that, apparently, makes it sound twice the frequency – whereas it really isn’t.

“Because the signal’s going up and down twice as much, even though you’ve changed the relationship of it, the ear perceives it as twice the frequency. It’s much like putting a picture up to a mirror and you see two of them, but there’s still only one real picture.”

Eventually, the octave-fuzz became a standard effect, featured in countless commercial stompboxes, and it remains one of the wilder, yet more expressive noise-makers available today.

Given the far-reaching success of the original concept, does Mayer ever regret not hitting the market with it himself in the late ’60s? “Nah,” he replies. “I had my other work. And besides, the interesting thing is that the copies never quite did it right. But I’ve got no sour grapes about any of that.

“The one matter about infringing the copyright, though, is they should at least pay respect, you know? If you’re making a copy of something, don’t tell me the copy’s better than the original when all you’re doing is ripping something off.”

Dave Hunter is a writer and consulting editor for Guitar Player magazine. His prolific output as author includes Fender 75 Years, The Guitar Amp Handbook, The British Amp Invasion, Ultimate Star Guitars, Guitar Effects Pedals, The Guitar Pickup Handbook, The Fender Telecaster and several other titles. Hunter is a former editor of The Guitar Magazine (UK), and a contributor to Vintage Guitar, Premier Guitar, The Connoisseur and other publications. A contributing essayist to the United States Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board’s Permanent Archive, he lives in Kittery, ME, with his wife and their two children and fronts the bands A Different Engine and The Stereo Field.

"The only thing missing is the noise from the tape loop." We review the Strymon EC-1 Single Head dTape Echo, a convincing take on a very special vintage tube Echoplex

"BigSky MX will be replacing the BigSky as my go-to reverb pedal. I’ve heard nothing that covers all the bases with such pristine and detailed audio quality." We crowned the Strymon BigSky MX the champ of multi-reverb pedals